Battlefield Visit: The Fight for Jesionową Górę

/By Seth Marshall

By the end of the summer of 1944, the situation for the German military was desperate. In June, the Western Allies had landed on the coast of Normandy and, after struggling through hedgerows for several weeks, broke out into open country and surrounded much of the 15th Army at Falaise. On the Eastern Front, the situation was even worse. On June 23rd, three years to the day after the German invasion, the Soviets had launched Operation Bagration against the Wehrmacht’s Army Group Center. In one of the largest land campaigns ever fought, some 1.6 million Red Army soldiers supported by over 3800 tanks, over 2000 assault guns, 32,700 guns and rocket launchers, and 7800 aircraft, assaulted the German front line. What resulted was nothing short of disastrous for the German Army along the Eastern Front. After six weeks of fighting, the Germans had been pushed out of almost all of Belarus, and some Soviet units had crossed the Polish frontier. By August 19th, 28 of the 34 divisions of Army Group Center had been destroyed. German losses amounted to 150,000-225,000 men killed or missing and another 150,000 captured. Soviet losses were also tremendous: 180,000 were killed or missing, and between 340,000-590,000 were wounded or sick. Material losses amounted to around 3,000 tanks and assault guns destroyed, over 800 aircraft destroyed, and 2,500 guns and howitzers destroyed. The shattered remnants of Army Group Center had withdrawn inside Poland, while the battered Army Group North withdrew towards East Prussia. Preparations were made as best they could to defend native German territory for the first time. Elsewhere, including Suwałki, German units prepared use the terrain in the region to slow the advance of the Red Army as long as possible.

Suwałki has long been in the path of armies, as a major intersection between numerous major roads and highways in northeastern Poland which led in multiple directions (including westwards towards Prussia and Germany). In the 20th Century alone, war had come to Suwałki three separate times before the fighting of 1944. From 1914-1915 during the First World War, multiple large battles between the Russian and German armies had taken place in the region, including Tannenberg, First and Second Masurian Lakes, and many smaller, but no less bloody, battles. In 1919-1920, the town was successively occupied by the Soviets, Lithuanians, and finally the Polish, though no battles actually took place in the area.[1] In 1939, the Soviets first took control of the city before it was turned over to the Germans in October. Several years into the occupation, the German administration changed the name of the city to Sudauen. The nearby dense Augustow Forest was also used as a base for Home Army units, who used the dark woods and swamps to hide their operations. Partisan activity around Suwałki, which had begun almost immediately after the Germans occupied the city, was enough for the Germans to mount multiple operations against them; throughout five years of occupation, at least 93 were executed. The Second World War touched Suwałki in other ways as well. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, a POW camp known as Stalag IF was set up in the Krzywolka suburb. Around 120,000 Soviet POWs were ultimately housed there and, owing to the generally appalling conditions in which the Germans kept the Soviet POWs and also to exposure and starvation, some 50,000 of these POWs died from 1941-1944.[2]

Occupying German soldiers guard Soviet prisoners in Suwałki during 1914-1915.

By late July 1944, with Bagration still in progress and the German Army in retreat, it became apparent that the area around Suwałki would again become an area of conflict. The terrain gradually sloped down towards the border with Prussia and Lithuania and the impassible and enormous Augustow Forest would force the Soviets to advance around it. Among the numerous roads leading in and out of the city, the road known today as Highway 8 runs northeast out of the city towards Lithuania. The Germans recognized that this road was the quickest means into Suwałki from the east and northeast. In order to prevent the Soviets from moving along this road, German high command decided to take advantage of the heights to the north of the city. Among these heights was Hill 252. Known to the Polish as Jesionowa Gora, as the Elefantenberg (Elephant Mountain) to the Germans, and Ash Mountain to the Russians, Hill 252 rises up to dominate the terrain for miles around. Situated on the southeastern bank of Lake Szelment, the hill offers clear sightlines up to 30km away from its top, providing an obvious advantage for both sides. More importantly, Hill 252 and several nearby slightly smaller hills all provided excellent observation on Highway 8.

The main German unit tasked with defense of this hill, along with much of the area to the immediate east of Suwałki, was the 170th Infantry Division. This division had seen action all through the war - first involved in the invasion of Denmark in April 1940, then during the fighting in France during the summer of 1940. The following year, the 170th had joined in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Among the major campaigns which the division took part in was the Crimean campaign in 1942 and the Siege of Leningrad, which didn’t end until 1944. Under the command of Brigadier General Siegfried Haß since February 1944, the division was a part of the Fourth Army under General of the Infantry Friedrich Hossbach. Like many other German divisions in Army Group Center, the division was severely understrength after Operation Bagration. Normal German divisional manpower strength for a 1944 formation was some 12,500 personnel, but the strength of the 170th in the fall of 1944 was likely closer to 50% of that strength. The division comprised of three Grenadier Regiments, four artillery battalions, an engineer battalion, and an anti-tank battalion which included 14 Sturmgeschutz assault guns. In addition to the 170th, other German units in the area included some Volkssturm units, which were essentially militia groups raised from ethnic Germans poorly equipped with older weapons and Luftwaffe units who, with too few aircraft remaining to service, had been transformed into infantry. Beginning in late summer, these units began digging numerous trench lines and anti-tank ditches in the area, and also began installing single-man concrete observation stands and small reinforced-concrete pillboxes.

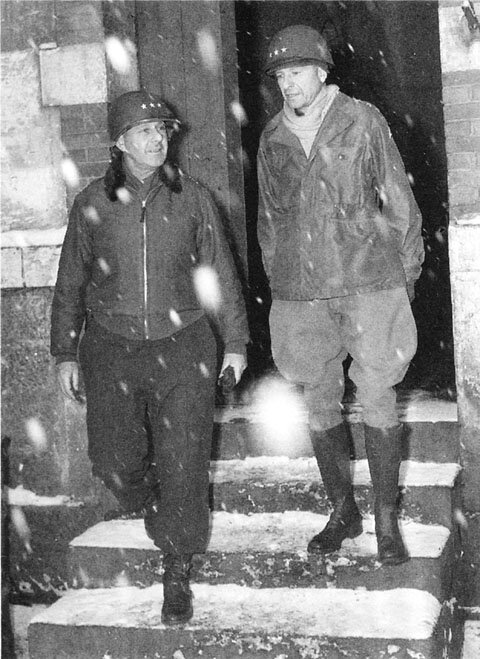

Brigadier General Siegfried Haß, who had commanded the 170th Infantry Division since early 1944. Photo source: ostvermisste-1944.de

German Volkssturm digging positions in East Prussia during the summer of 1944. Photo source: historyimages.blogspot.com.

The main Soviet unit which would be tasked with taking both Suwałki and Hill 252 was the 31st Army, which fielded eight rifle divisions. The 31st Army, commanded during this time by General Vasily Glagolev, had been activated in July 1941 after the German invasion began the month prior. Entering combat in October 1941, the Army spent the next 16 months fighting around Rzhev on the western approaches to Moscow. Beginning in the spring of 1943, the 31st Army had fought its way westward across the Dnieper River, and taken Smolensk in the fall of 1943. In 1944, the Army had advanced into Belarus and participated in Operation Bagration, which had finally brought it into the Suwałki region. The two main divisions that would see combat in the area were the 173rd and 352nd Rifle Divisions; the 173rd would lead an attack to take Suwałki, while the 352nd would have the difficult task of taking Hill 252. Normally, a Rifle Division at full strength would consist of some 11,700 men, including three Rifle Regiments. With the Army having been fully involved in Bagration, it’s likely that the strength for the 173rd and 352nd Rifle Divisions was probably closer to 60-70%. In command of the 352nd was Major General Nikolai Mikhailovich Strizhenko.

Major General Nikolai Mikhailovich Strizhenko, commander of the 352nd Rifle Division. Photo source: Suwalki Military History Association.

Fighting began in late summer 1944 in the Suwałki region. Hoping to take the hill in a quick assault, the Soviets organized an infantry attack supported by tanks on August 6th. Attacking the hill from the north and east, the Soviets immediately came under heavy fire from German Sturmgeschutz assault guns and anti-tank guns positioned on the hill. Soon, 15 burning Soviet tanks were left along the front of the hill, and the attack was called off. After this failure, fighting began degenerating into relatively stagnate warfare. Because of the terrain, Soviet infantry attempted to dig trenches towards the hill, trying to give their men cover to move through before assaulting the hill, but this was to prove unsuccessful. The Soviets also airdropped propaganda leaflets over German lines, attempting to encourage the Germans to surrender. By late September 1944, the Soviets had reached the defensive line set up along Hill 252. By then, the German defenders had been able to fortify two smaller hills, Hill 234 and Hill 239, which were more or less forward positions for the strongpoint on Hill 252. Fighting around the hills began in mid-September and would reach a climax during seven days from September 26th to October 4th. This increase in the fighting around the hills was due to the Soviet desire to seize the hills as a jumping-off point for a follow-on offensive to take Suwałki. The 352nd was to bear the brunt of the fighting during this period, while the 173rd was tasked with taking Hill 195 near the village of Bilwinowo. The Soviets ordered the soldiers from two of their penal companies to lead the attack, which cost these units heavily; between September 21-30th, the 135th and 140th Penal Companies lost 108 killed.[3] With several previous efforts to take Hill 252 having failed, the leadership of the 352nd decided to change their tactics. A special battalion-sized unit was formed from men from the 1162nd Rifle Regiment, led by Senior Lieutenant Hlovistov and Lieutenant Homiakowa Hilstowa, and tasked with sneaking across no-man’s land and destroying German bunkers and machinegun emplacements. Early on the morning of September 26th, these men moved across the cratered landscape and hid in shell craters and trenches just 100 meters short of the bunkers. To distract German attention, a diversionary attack was carried out by a Soviet scout unit further north. Additionally, the Soviets planned on triggering several smoke pots to provide a smokescreen over the battlefield and allow the infantry to advance across the open fields south to the hill.[4]

A knocked-out T-34-85 on the outskirts of Nemmersdorf, October 1944. Fifteen tanks of this type were lost in the first attempt to take the hill. Photo source: Alamy.com

A Soviet document showing the distances between the Soviet and German lines on September 16th. Photo scanned by Mirosław Surmacz. Source: Suwalki Military History Association.

The Soviet plan for air support on September 26th involved two squadrons of Il-2 Shturmoviks, as shown above. Photo scanned by Mirosław Surmacz. Source: Suwalki Military History Association.

The Soviet plan for the use of flamethrowers on September 26th. Photo scanned by Mirosław Surmacz. Source: Suwalki Military History Association.

At daybreak, Soviet artillery opened fire on the German fortifications. Accurate fire destroyed several bunkers, while mortar fire cut down many exposed German soldiers. To assist in the bombardment, two squadrons of Il-2 Shturomvik attack aircraft hammered the German lines on the hilltop continuously, flying circles around the German positions until their ordnance was expended. Before the Soviet artillery ceased firing, the assault battalion began attacking the Germans, led by Lieutenants Hlovistov and Hilstowa. They quickly breached the German trench lines and began engaging the infantry there in hand-to-hand combat. Lieutenant Schnell, an officer with the 170th Infantry Division, later recalled the fighting on the hill:

“The Volkssturm and other work units have built catchment positions as part of the East Prussian protective position. Unfortunately, the trenches are all on the eastern slopes and so we have to hold the notorious curtain positions. As the Russian grenade launchers can shoot into our trenches without difficulty- they are very wide at the top because they were made in the evening- the losses are too great, so the positions have to be given up again and again… Soon we are fighting on the front slope. Now the Russians are sitting in our old front slope position and we, parts of the 401st Grenadier Regiment with former Air Force soldiers, with me as VB. And two as radio operators, sit on the western side of the slope in a collecting ditch. We are now digging in competition with the Russians in order to be the first to reach the summit of the Elephant Mountain… One disturbs the other in his work with raiding parties, and the hand grenades are thrown back and forth. It it’s a position that does not allow any rest, day and night can only be survived with the utmost effectiveness. It is constantly spoken in a whisper, because the enemy can overhear and then the hand grenades will fly immediately and Russian grenade launchers are used, we miss them very much in the war in Russia.”[5]

Realizing they were being overwhelmed, the Germans pulled off the hilltop. The following day, the Germans brought up several assault guns and prepared to launch a counterattack. A large group of artillery had also been gathered to support the attack. However, Soviet observers on the hill saw this German grouping of artillery and called for fire on the position, destroying a number of guns causing enough mayhem that the counterattack was called off. However, the Soviet success was short-lived – the next day, the Germans counterattacked and pushed the Soviets back off the hill. Fighting would seesaw back and forth during the next several days, and at some points both the Germans and Soviets occupied portions of the hill, and the distance between the opposing lines was as little as 30 meters, close enough for both sides to throw hand grenades at one another. On several occasions, the Soviets brought up flamethrowers in attempt to drive the Germans off the hilltop. Some Soviet survivors of the battle reported that in one instance in late September, Lieutenant Colonel Kolesnikov Sergei Charlampievich, commander of the 1158th Regiment, had ordered his supporting artillery to fire on his own position as his unit was being overwhelmed by a German attack.[6]

Several Soviet soldiers recounted their experiences during the fighting for the hill in September and October. Grigory Fedorowicz Denisenko, a scout with the 1160th Rifle Regiment, later recalled:

“The battle for the mountain goes on all the time, continuous shots, explosions. Debris is flying in the air all the time. On September 28, fierce fights for the mountain have been going on for almost a week. Several times the hill changes hands. We lost a lot of soldiers. At one point, we captured the hill and positioned artillery too quickly on the mountain. The Germans recaptured the mountain in a counterattack and we lost two guns… We attack on October 4th and 5th and again on October 11th and 12th. Autumn, mud in the trenches. You can’t see anything at night, and I stumble over stones, fall into water pits… On October 17th, we are ordered to make a reconnaissance, enter the forest with some difficult and become lost. After wandering around for an hour and a half, we finally get to where we need to be. Several scouts captured a German- he was serving as a sapper. He is 57 years old and wounded in both legs from a grenade blast. After interrogating him, we moved him to a crater and shot him. “[7]

In a week of intense fighting, the Soviets lost over 1,000 soldiers killed in the fighting for the hill. German losses during the same period are unknown.[8]

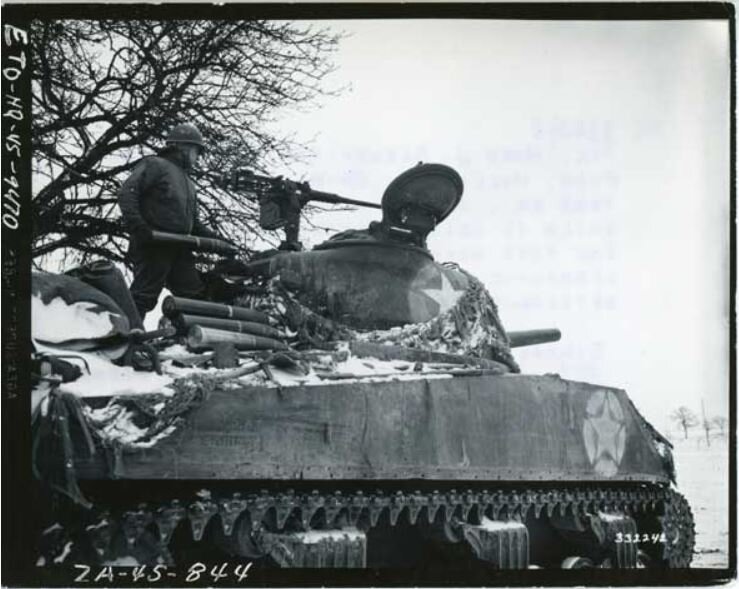

A knocked-out Sturmgeschutz III assault gun, with a dead crewman in the foreground. A number of these assault guns provided valuable anti-tank capabilities for the Germans on Hill 252. Photo source: uncensoredhistory.blogspot.com.

Soviet map showing a partial ascent of Hill 252 on October 1st- note how many battalions were thrown into this attack. Photo scanned by Mirosław Surmacz. Source: Suwalki Military History Association.

While the most intense phase of fighting had passed, fighting over the hill continued for weeks. Despite the loss of so many soldiers, and with the hill still in German hands, the commander of the Soviet 3rd Belorussian Front, General Ivan Chernyakhovsky, received an order from Soviet Supreme Command Headquarters to mount a major offensive into Eastern Prussia. The order, known as Directive No. 220235, read “Prepare and conduct an offensive operation… with the aim of interacting with the 1st Baltic Front, to defeat the Tilsit-Insterburg grouping of the Germans and capture the area of Konigsberg.”[9] In order to meet this directive, Chernyakhovsky planned to use the 5th and 11th Guards Armies to break the German defensive lines, while the 2nd Guards Tank Corps would exploit the breach, with the 28th Army acting as follow-on support. In support of this operation, the 31st and 39th Armies would conduct supporting operations of their own. The 31st Army, of which the 352nd Rifle Division was a part of, would first take Suwałkibefore continuing westwards and assaulting Gołdap.[10] This offensive was to become known as the Gubińsko-Gołdap. Before the offensive began, Chernyakhovsky released the directive from higher command to his subordinates, adding his own note at the end:

“Soldiers, sergeants, officers and generals of the 3rd Belorussian Front, we were honored to be the first to break into the den of the fascist beast. Remember, the fascist invasion began from these places. How many disasters it brought to the world! How many destroyed cities and villages, how many exhausted and tormented people were burned in crematoria, the earth was doused with blood and covered with burial mounds… we were honored, we were the first to raise the sword over the head of the fascist beast in its den. Let us deserve our glorious combat mission, fulfill our duty, and let the whole world breathe a sigh of relief.”[11]

On October 16th, the offensive began. Chernyakhovsky had concentrated a massive amount of artillery for a preparatory bombardment, which began in the early morning hours. The following day, the 31st Army began its own supporting operations with an attack on Hill 252, hitting the hill with another large bombardment. The following day, the 173rd Rifle Division began an attack towards Suwałki. At 7PM, a thirty-minute artillery bombardment began, and the division began attacking along the Bilwinowo-Czerwonka line. Elements of the 170th Infantry Division resisted fiercely, and the Soviet attack ground to a halt in the dark. The next day, the Soviets began another attack. A 20-minute bombardment began at 4PM, which was followed by an infantry assault. Again, the Penal Companies were ordered forward first, with the 1311th Rifle Regiment following. The Soviet infantry attack concentrated on Hill 195, near the village of Bilwinowo. The Soviets lost 50 killed in the assault, but broke through the German trenches and took the hill. Now under pressure all along their line and realizing that a much larger Soviet strategic offensive was underway, the hard-pressed German 170th Infantry Division began withdrawing, leaving a rearguard to prevent the Soviets from following them. Hill 252, which had been fought over for over a month, was finally abandoned to the Soviets.

Late on October 20th, with the 173rd Rifle Division having secured the town of Bilwinowo, Major General Provalov ordered his division to continue advancing towards Suwałkiby securing the towns of Krzemianka, Biala Woda, and Zywa Woda. The attack began at 9PM on the 20th and before the next morning all of the towns had been captured. Without pausing to rest, the division was ordered to cross the Czarna Hancza River. After daybreak, the 1311th and 1315th Rifle Regiments crossed the river under fire from the opposite bank, overwhelmed the German trenches, and soon began advancing along the Osowa-Suwalki road. By the evening of October 21st, the 173rd had reached the outskirts of Suwałki. Suwałki was still held by large elements of the 170th Infantry Division, along with a large number of Volkssturm conscripts under the command of Colonel Kluger. On October 22nd, the Soviets began their attack on the city, with most of the fighting taking place in the St. Alexander suburb of the city. The next day, the Soviets launched an attack around the north end of the city, which threatened to cut off the main avenue of retreat for the Germans. The remaining units from the 170th Infantry Division then withdrew from the city to avoid being cut off and surrounded. By the end of the day, the city had been secured. In the week of fighting to take the city, the 173rd had lost approximately 400 killed, while the Germans had lost 600 killed defending Suwałki. Among the dead was Colonel Kluger. Despite the death toll, the fighting in the city proper was not considered particularly intense - further north, German resistance was far more substantial.[12]

Damage to St. Alexander Cathedral in Suwalki. The two bell towers were destroyed by explosives by the withdrawing Germans. Photo source: ostvermisste-1944.de.

In contrast to the resistance encountered by the 31st Army, the rest of the 3rd Belorussian Front further north had immediately encountered very tough resistance in the face of the 4th Army and 3rd Panzer Army. After taking heavier losses than anticipated, Chernyakhovsky was forced to commit the 2nd Guards Tank Army to the fight much sooner than he had planned in order to break through the German lines. The 2nd Guards Tank Army and the 11th Guard Army finally broke through the second layer of German defenses on October 20th, but again hit resistance on the following day. This additional delay caused Chernyakhovsky to commit his Front’s reserve force, the 28th Army.[13][14] On October 22nd, Gumbinnen was captured by the Soviets, but then recaptured by the Germans just two days later. Seeing that the Soviets were overextended and stretched thin after having taken heavy casualties, German commanders were able to cobble together a counterattack force which quickly moved along the Soviet force’s flanks and cut-off several units, despite itself being heavily outnumbered. Heavy tank combat resulted near the towns of Großwaltersdorf and Gołdap. The German attack completely took the momentum out of the Soviet attack and, by October 30th, the offensive was over. The Germans retook Gołdapin early November, and the lines stabilized for the next two and a half months.[15][16][17]

Soviet map showing the progress of the 31st Army in during the mid-October offensive. Photo scanned by Mirosław Surmacz. Source: Suwalki Military History Association.

German infantry talk to the commander of a tank or assault gun while retaking Goldap in early November. Photo source: Warfare History Network.

Panthers from the 5th Panzer Regiment in action near Goldap during the First East Prussian Offensive. Photo source: Warfare History Network.

After the fighting around Suwałki, the 170th Infantry Division withdrew 10km to the west and consolidated around the town of Filipów. The 352nd and 173rd Rifle Divisions both continued in their offensive operations, with the 352nd becoming heavily involved in the fighting around Gołdap. The battle for Hill 252 and the week of combat around Suwałki had resulted in the deaths of over 5,100 Soviet soldiers. German casualties during the same period is unknown, but is likely also in the thousands. The overall casualty figures for Chernyakhovsky’s offensive were heavy for both sides: the Soviets had suffered nearly 80,000 casualties, including nearly 17,000 killed. The Germans suffered fewer casualties, with just over 16,000 total, including 6,800 killed or missing, but this represented a much larger percentage of their available forces. Material losses were heavy too, particularly in terms of tanks and armored vehicles; the Germans lost 115 tanks and assault guns destroyed, while the Soviets lost 914 tanks and assault guns destroyed.[18] These losses were indicative of the heavy armored combat taking place in the region. Another aspect of the East Prussian offensive was the behavior of Soviet troops towards German civilians. On October 23rd, the Germans had retaken the Prussian town of Nemmersdorf, which had been captured by the Soviets days earlier. At least 74 civilians and over 50 French and Belgian POWs were brutally raped and executed by Soviet soldiers, eager to avenge the carnage brought on their own homeland by the Germans. This massacre became an early example of how the Red Army would wreak its revenge on the Germans, but was still exploited by the Nazi propaganda ministry to stir up patriotic fervor.[19] After withdrawing from Hill 252, the 170th Infantry Division withdrew first to Filipów, then on towards a line along the Rospuda river, which ran through Bakałarzewo , Raczki and Augustów. Both armies would then hold these lines until late January 1945.

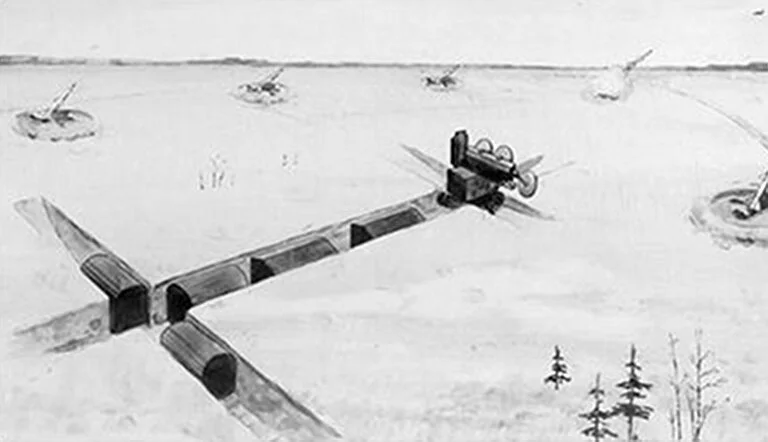

Today, the landscape has changed significantly. Hill 252 still bears scars from the fighting- the main trench lines which were dug by the Germans and then occupied and enlarged by the Soviets still remain in place. Standing from the German positions, it is very easy to see why they chose this piece of terrain to block the Soviet advance- from the trenches, the Germans would have had a clear view of the Soviets trying to force their way across the fields to the north and west of the hill and the marshy ground to the east. Any tanks moving across the fields would have been exposed to German anti-tank fire, and then could only have advanced up the hill from the east where the slope permits tank movement. Further up the hill, a number of single-man concrete fighting positions remain, partially-filled in with dirt and plants. In a bizarre twist, much of the top of the hill and portions of the slope are taken up with ski lifts and slopes. The ski slopes have covered over portions of the trench line, and trees have reclaimed other areas. Soviet drawings of the hill 1944 show that by mid-September 1944, artillery fire had removed all trees from the hill. Still, periodically more remnants of the fighting surface. Several years ago, a portion of the hill gave way and revealed a number of corpses, along with several live hand grenades. Artifact hunters visit the hill from time to time, scanning with metal detectors to find items left behind from the fighting- on one visit to the hill, I and several guides found numerous pieces of shrapnel, the burst remnant of a Soviet 82mm mortar, and pieces of barbed wire. Two kilometers to the southeast, on Hill 249, more remnants of the fighting in late 1944 remain. Here, two observation bunkers remain facing north and east- both would have provided German observers with excellent sightlines on nearby Highway 8. Both bunkers have sustained several hits from tank or artillery fire. Additionally, a criss-cross network of trenches remain on the hill. Further west, in Bakałarzewo, more traces of the fighting remain. Here, along the pre-war border between Poland and East Prussia, several bunkers remain on the west bank of the Raspuda River, overlooking a wide gorge. The Germans held these older bunkers for three months from late October 1944 until the Vistula-Oder Offensive began in January 1945. On the eastern bank, there are fewer signs of the fighting. Numerous patches of woods have grown up in the intervening 75 years, changing much of the landscape. There are still some one-man fighting positions and the remains of an anti-tank ditch which are just north of the town. Bakałarzewo itself was severely damaged in the fighting- the church was completely destroyed by Soviet tank and artillery fire after it was discovered that the Germans were using the bell towers as observation points for their forward observers. The landscape then has changed significantly, but many traces of the fighting remain today.

The fighting for Hill 252 was some of the heaviest fighting in eastern Poland during 1944. Despite being greatly outnumbered by Soviet men and equipment, the Germans were able to maintain control over the hill and its surrounding area for weeks before finally being pushed off the hill in October. The failure to capture Hill 252 sooner delayed the Soviet capture of Suwałki, which in turn hurt their ability to move into central Poland. Though many of the marks left by the battle have since faded, and the hilltop itself has become home to a ski resort, Hill 252’s importance as key terrain in the region is still clear when visiting the site; it continues to provide a dominating view of the surrounding region, and would even today be considered a highly valuable piece of terrain.

View of the hill from the West. Today the hill is home to a ski resort, which doubles in the summer with a mini-golf course, rope challenge and water ski rental. Photo source: Author.

Several trenches around the hill remain today. The first trench line runs all around the north side of the hill. Phot source: Author.

Another view of the German trench line on the north side of the hill. Photo source: Author.

One of the many single-man fighting positions on the hill which remain today. Thousands of these were emplaced throughout East Prussia during 1944. Photo source: Author.

A view of the second German trench line, further up the hill. Photo source: Author.

Mid-way up Hill 252, a portion of the earth gave way about 5 years ago. A number of human remains were exposed- considering most Soviet soldiers were buried in the cemetery in Suwalki, it seems likely that these were German. Several live hand grenades were also found with the bodies. Photo source: Author.

A view from the top of the hill, looking north. The open ground at the bottom of the hill would have been where Soviet infantry charged across towards the German defenses. Photo source: Author.

One of two German observation posts on Hill 249. Photo source: Author.

This cellar was used by the German artillery officers of the 170th Infantry Division to coordinate the fires for the hill’s defense- the cellar is just south of the hill itself. Photo source: Author.

The Soviet military cemetery at Suwalki. Over 5500 soldiers are buried here, most in unmarked graves. Photo source: Author.

Sources

1. Glantz, David M. “The Failures of Historiography: Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–1945).” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, vol. 8, no. 4, 1995, pp. 768–808., doi:10.1080/13518049508430217.

2. Frieser, Karl-Heinz, et al. Germany and the Second World War. Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighboring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017.

3. Eilender, Kasriel. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN SUWALKI, JewishGen, kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/suwalki/History.htm.

4. “The History of Podlaskie Voivodeship.” Wrota Podlasia, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Podlaskiego, 6 Jan. 2009, www.wrotapodlasia.pl/en/region/history/The_history_of_Podlaskie_Voivodeship.html.

5. Friedrich, Hagen. “Fighting of the 170th Infantry Division for Suwalki.” Ostvermisste 1944, 2008, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Suwalki%201944.htm.

6. Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Jeleniewo-Höhe 252.” Wo Sind Sie Geblieben? - Jeleniewo - Hoehe 252, 2011, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Jeleniewo-Hoehe%20252.htm. Translated from Polish to German in 2011, accessed in 2020.

7. 170. Infanterie-Division, 25 Aug. 2011, www.axishistory.com/books/150-germany-heer/heer-divisionen/3667-170-infanterie-division.

8. Mctaggert, Pat. “Goldap Operation: Soviets in the Prussian Heartland.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 16 Dec. 2018, warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/goldap-operation-soviets-in-the-prussian-heartland/.

9. Buttar, Prit. Battleground Prussia: the Assault on Germany's Eastern Front 1944-1945. Osprey Publishing , 2010.

10. “STAROSTWO POWIATOWE W SUWAŁKACH.” II Wojna Światowa - Powiat Suwalski, Minister of Administration and Digitization, Apr. 2019, www.powiat.suwalski.pl/kat/nasz-powiat/historia/ii-wojna-swiatowa.

11. Anisimovna, Maistrenko Tatiana. Scorched Youth.

12. Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Suwalszczyzna w Ogniu Walk II Wojny Światowej – Raczki 1944/45.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of History, 9 Nov. 2017, ojczyzna-suwalszczyzna.pl/suwalszczyzna-w-ogniu-walk-ii-wojny-swiatowej-raczki-194445/#more-941.

13. Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Jeleniewo-Höhe 252.” Wo Sind Sie Geblieben? - Jeleniewo - Hoehe 252, 2011, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Jeleniewo-Hoehe%20252.htm. Translated from Polish to German in 2011

14. http://www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Reisebericht-Suwalki.htm. Friedrich Hagen. Published 2011, accessed 2020.

15. Müller, Ferdinand. “My War Years.” Wo Sind Sie Geblieben? - Reisebericht Jeleniewo - Suwalki 2011, Friedrich Hagen, 2011, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Reisebericht-Suwalki.htm.

16. Technical Manual: Handbook on German Military Forces, 15 March 1945. TM-E30-451.

17. Glantz, David. “The Great Patriotic War and the Maturation of Soviet Operational Art: 1941-1945.” Soviet Army Studies Office, 1987. Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

18. Anisimovna, Maistrenko Tatiana. Scorched Youth.

19. Surmacz, Mirosław. “Działania Militarne Na Ziemi Bakałarzewskiej z Lat 1944/1945.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of Military History, 17 July 2014, ojczyzna-suwalszczyzna.pl/dzialania-militarne-na-ziemi-bakalarzewskiej-z-lat-19441945/.

20. Surmacz, Mirosław. “Bitwa o Jesionową Górę 1944.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of Military History, 17 July 2014, ojczyzna-suwalszczyzna.pl/bitwa-o-jesionowa-gore-1944/.

[1] “The History of Podlaskie Voivodeship.” Wrota Podlasia, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Podlaskiego, 6 Jan. 2009

[2] “STAROSTWO POWIATOWE W SUWAŁKACH.” II Wojna Światowa - Powiat Suwalski, Minister of Administration and Digitization, Apr. 2019, www.powiat.suwalski.pl/kat/nasz-powiat/historia/ii-wojna-swiatowa

[3] Surmacz, Mirosław. “Działania Militarne Na Ziemi Bakałarzewskiej z Lat 1944/1945.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of Military History, 17 July 2014, ojczyzna-suwalszczyzna.pl/dzialania-militarne-na-ziemi-bakalarzewskiej-z-lat-19441945/.

[4] Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Jeleniewo-Höhe 252.” Wo Sind Sie Geblieben? - Jeleniewo - Hoehe 252, 2011, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Jeleniewo-Hoehe%20252.htm. Translated from Polish to German in 2011

[5] http://www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Reisebericht-Suwalki.htm. Friedrich Hagen. Published 2011, accessed 2020.

[6] Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Jeleniewo-Höhe 252.” Wo Sind Sie Geblieben? - Jeleniewo - Hoehe 252, 2011, www.ostvermisste-1944.de/Jeleniewo-Hoehe%20252.htm. Translated from Polish to German in 2011

[7] Surmacz, Mirosław. “Bitwa o Jesionową Górę 1944.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of Military History, 17 July 2014, ojczyzna-suwalszczyzna.pl/bitwa-o-jesionowa-gore-1944/.

[8] Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Suwalszczyzna w Ogniu Walk II Wojny Światowej – Raczki 1944/45.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of History, 9 Nov. 2017, ojczyzna-

[9] Anisimovna, Maistrenko Tatiana. Scorched Youth.

[10] Mctaggert, Pat. “Goldap Operation: Soviets in the Prussian Heartland.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 16 Dec. 2018, warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/goldap-operation-soviets-in-the-prussian-heartland/

[11] Anisimovna, Maistrenko Tatiana. Scorched Youth.

[12] Surmacz, Miroslaw. “Suwalszczyzna w Ogniu Walk II Wojny Światowej – Raczki 1944/45.” Ojczyzna Suwalczyzna, Suwalki Association of History, 9 Nov. 2017, ojczyzna-

[13] Glantz, David M. “The Failures of Historiography: Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–1945).” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, vol. 8, no. 4, 1995, pp. 768–808., doi:10.1080/13518049508430217

[14] P. 612-613- Frieser, Karl-Heinz, et al. Germany and the Second World War. Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighboring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017.

[15] P.614-615- Frieser, Karl-Heinz, et al. Germany and the Second World War. Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighboring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017.

[16] Mctaggert, Pat. “Goldap Operation: Soviets in the Prussian Heartland.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 16 Dec. 2018, warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/goldap-operation-soviets-in-the-prussian-heartland/

[17] Buttar, Prit. Battleground Prussia: the Assault on Germany's Eastern Front 1944-1945. Osprey Publishing , 2010.

[18] P. 616- Frieser, Karl-Heinz, et al. Germany and the Second World War. Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighboring Fronts. Oxford University Press, 2017.

[19] Mctaggert, Pat. “Goldap Operation: Soviets in the Prussian Heartland.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 16 Dec. 2018, warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/goldap-operation-soviets-in-the-prussian-heartland/