Tools of War: the SA-2 Guideline

/Photo source: ausairpower.com

For American fighter-bomber pilots flying above North Vietnam in the late 1960s, ground fire and Surface-to-Air-Missiles (SAMs) were far more feared than the occasional MiG. The most dreaded of these came in the form of the SA-2 “Guideline” SAM, a telephone-pole length missile which inflicted many losses on US aircraft over the course of the war. The Guideline was destined to become the most widely-distributed SAM during the Cold War.

By Seth Marshall

In the 1950s, with Cold War tensions only increasing, the United States had begun building large numbers of jet-powered bombers which were capable of aerial refueling and could fly all the way to their potential targets in the Soviet Union. While the Soviets possessed a substantial number of fighter aircraft, the Soviets felt that their numbers were not great enough to stop all of the bombers. In response to the US bomber threat, the Soviets began building surface-to-air missiles. The first of these was the SA-1. However, almost as soon as it was introduced, it was realized that there were problems with the new missile- it was limited to one location (the system was fixed and could not be moved), it was effective against large formations but not against smaller groups of aircraft, and it had limited targeting capabilities.[1] Subsequently, it was decided to begin designing a newer missile which would be better suited for tactical operations.

In 1953, the Almaz design bureau presented its missile design, which had been created by Pyotr Grushin. The missile was made up of two stages. The first contained solid propellant to accelerate away from the launch site, and the second contained a hypergolic liquid propellant. The warhead for most of the earlier Guideline variants weighed 195kg, and was usually high explosive-fragmentation. Different fuses, included proximity, contact and command fuses were produced for use. The blast radius of the warhead depended on the altitude of detonation- at the high levels where U-2 reconnaissance planes flew, it could be as much as 244m. At lower altitudes against fighter-bombers, the blast radius was lethal out to 65m. A nuclear-armed variant of the SA-2 was produced, intended for use against bomber formations. This missile, the SA-2e, was armed with a 295kg warhead which had an estimated yield of 15 kilotons, the same explosive power as the bomb used against Hiroshima.[2] The new missile was designed from the start to be more mobile than its predecessor. The missile itself was launched from a SM-90 single rail launcher, which was carried by a transloader trailer and pulled by a Zil truck.[3] Each missile battery was to contain six launchers and one RSNA/SNR-75 “Fan Song” radar. This radar was also designed to be mobile- several large dishes were mounted to a single trailer. These dishes provided azimuth and altitude information for targets, which was then relayed to the missiles. Fan Song radars were provided targets by higher echelon radars, such as the Spoon Rest radar.

The “Spoon Rest” radar which provided the target acquisition information and fire control for the SA-2 battery.

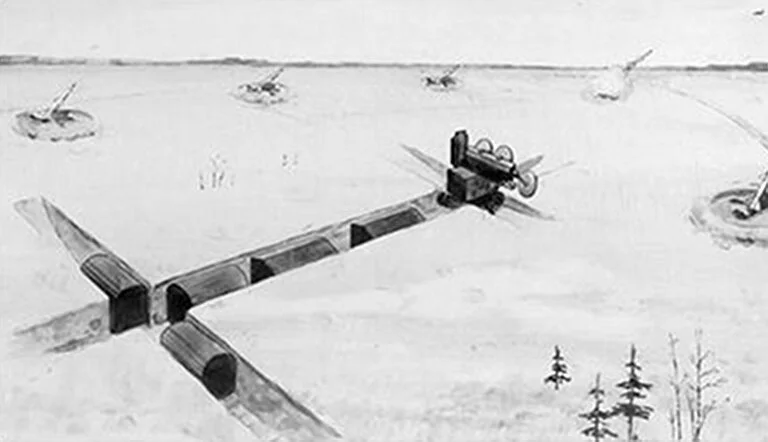

An illustration showing the ideal arrangement of the battery command, fire control radar, and other administrative functions of an SA-2 battery. (Photo source: ausairpower.com)

The firing process for the new missile began at the SAM Regimental-level. There, a Spoon Rest target acquisition radar, which had greater range and altitude capabilities than the Fan Song, would acquire target aircraft entering the region. The Spoon Rest radar would then send this information to its subordinate batteries, whose Fan Songs would pick up the tracks. The missile launcher was then oriented towards the incoming aircraft while the Fan Song and computers in the command trailer plotted range and angle information. Typically, two missiles would be fired at once; a radio uplink from the launch site guided the missiles to their target and detonation.[4]

The first S-75s began to be deployed in the late 1950s across the Soviet Union, China, and various Eastern Bloc countries. The first use of the S-75 came on October 7, 1959 near Beijing, China. An RB-57 Canberra reconnaissance aircraft, loaned by the US to the Republic of China (Taiwan) Air Force, was shot down from 65,000 feet, killing the pilot.[5] At the time, the missile was still secret, so it was claimed that the Taiwanese aircraft was shot down by fighters. However, the following year it became glaringly obvious that the Soviets had developed a new missile when on May 1, 1960 a CIA U-2 spy plane was shot down by an S-75. Several years earlier, under direction from the Eisenhower administration, U-2 overflights over the Soviet Union had begun to determine Soviet nuclear capabilities. The Soviets were well aware of the flights, but since the U-2s flew at altitudes at or above 70,000 feet, their fighters at the time were not able to intercept them. The Soviets fired a number of missiles at the U-2, flown by Francis Gary Powers; one exploded near the aircraft and a second scored a direct hit. Powers bailed out and was captured by Soviets; the U-2 wreckage was recovered remarkably intact. This led to a major incident during the Cold War, forcing the US to admit that it had been sending reconnaissance planes over the Soviet Union and was a propaganda coups for the Soviet Union and its premier, Nikita Khruschev.[6]

Francis Gary Powers, whose U-2 was shot down on May 1, 1960 by an SA-2, causing an international incident. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Major Rudolph Anderson, an Air Force U-2 pilot who was shot down and killed during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Through the first five years of the 1960s, several more aircraft were shot down by S-75s, which by then had earned their own NATO designation- the SA-2 “GUIDELINE.” Several Taiwanese U-2s were shot down during the 1960s by SA-2s while flying over China. Another critical incident involving an SA-2 shootdown of a U-2 occurred on October 27, 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Unlike the Powers incident two years earlier, this shootdown was not authorized by the Soviet leadership, and was ordered by a local commander on the ground in Cuba. The pilot, USAF Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed. Despite immense pressure from the US military leadership, President John F. Kennedy resisted the demand to retaliate on the offending missile battery and ultimately negotiated a deal which defused the crisis.[7] The effectiveness of the SA-2 against the U-2 in numerous engagements during the early 1960s led directly to Lockheed developing the SR-71, an aircraft which could fly beyond the performance envelope of the SA-2.

By the mid-1960s, the SA-2 was in wide circulation among the Soviet Union and its satellite countries. In the Soviet Union itself, the CIA estimated that SA-2 deployment was completed by the end of 1965; the CIA had identified 870 sites supporting six launchers each by that time, with another 160 possible alternate sites identified.[8] Among the Soviet client states which used the SA-2 were East Germany, Egypt, Mongolia, North Korea, North Vietnam, and China. China initially received only a small number of SA-2s, but soon copied the design and began building it in large numbers as the HQ-1. Despite the wide deployment of the weapon system, it would be in North Vietnam that the SA-2 would see its most extensive use.

American involvement in Vietnam had begun early in the 1960s and ramped up in earnest after the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964. Soon, American aircraft were flying numerous sorties over South Vietnam and some areas of North Vietnam. To defend against this, the Soviet Union supplied the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) with SA-2s, brought its personnel to the Soviet Union for training, and sent advisors to assist the NVA in operating the new sites.[9] In April 1965, the US discovered the first five SAM sites under construction. The discovery surprised and dismayed US planners, who wanted to target the sites immediately. However, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara believed that the US should pursue a policy of moderation, fearing an escalation in the war if US planes hit missile sites manned by Soviet advisors. As a result, the construction went on unhindered and on July 24, 1965, an SA-2 shot down one F-4, damaging two others with the resulting explosion. At the time, US aircraft were flying at higher altitudes to avoid the abundance of AAA used by Vietnam which proved deadly at low altitudes.[10] The effect of this shootdown was almost immediate. Three days later, the US Air Force launched Operation Spring High, intended to destroy several of the offending SAM sites, using 48 F-105 “Thunderchief” fighter-bombers from four different Tactical Fighter Squadrons stationed at a pair of Thai bases. However, the Vietnamese had foreseen this possibility, replaced the real SA-2s with dummies, and ringed the area with numerous AAA batteries. Four of the F-105s were shot down in the vicinity of the target, and half the remaining aircraft were damaged- while attempting to make an emergency landing, another F-105 lost control and collided with a second, killing both pilots.[11]

US pilots were initially not well-prepared to deal with the threat of SAMs. Much of the aircraft used by the Americans were being used in ways that they had not originally been envisioned for. The F-105, the primary fighter-bomber used by the Air Force, was originally designed as a high-speed nuclear bomber, intended to fly at supersonic speeds at low-levels before zooming to higher altitudes to deliver its payload. The F-4, a large fighter used by both the Air Force and Navy, was conceived as a bomber interceptor. Neither of these aircraft, along with most other US types, were equipped with effective countermeasures to the new threat. Their pilots had also not been trained on how to defeat or evade incoming missiles. It would take several months of combat experience and analysis to develop solutions to these problems.

An RF-4C Phantom is hit by shrapnel from an exploding SA-2 on August 12, 1967- both crew survived the shoot-down, but CPT Edwin Atterberry was killed while in captivity. (Photo source: ausairpower.com)

An F-105D fighter-bomber has been damaged by a near-miss from an SA-2. (Photo source: ausairpower.com)

A typical star-shaped arrangement for an SA-2 battery- the tell-tale arrangement frequently drew the attention of American aircraft- North Vietnamese battery operators would later use different arrangements to conceal their sites as the Vietnam War progressed. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

After their initial experiences, US pilots discovered that the SA-2 had flaws which could be exploited. Because of the shear size of the missile, launches and incoming missiles could be spotted by pilots and crew after being alerted by an in-cockpit missile alarm. Then the pilots could take evasive action. One method involved diving towards the missile, forcing the SA-2 to change direction, then pulling up sharply at the appropriate moment, a maneuver which the SA- could not match.[12] Another tactic involved flying the aircraft towards the sun, which had the potential of fooling the infra-red seeker head on the missile. Soon, various improvements came to the US fighter-bombers to increase their odds against the North Vietnamese air defenses. In December 1965, radar homing and warning (RHAW) receivers were installed on the first F-105s and would become commonplace by mid-1966.[13] This system included a scope inside the cockpit with what resembled a crosshair with three concentric rings. A strobe on the scope would show the pilot or weapon officer the direction and distance to the radar station detecting the aircraft. Pilots coined the phrase “three-ringer” for an indication that was particularly close. If a launch was detected, a red light came on and a tone would sound inside the pilot’s helmet.[14] This system could also detect the radar of some of the AAA guns defending North Vietnam. Beginning in September 1966, F-4s were equipped with QRC-160 wing pods which were intended to jam the SAM battery’s radar.[15] The most radical of the US reactions to the SAM threat was the development of the so-called “Wild Weasel” units- fighter-bombers specifically modified and used to destroy SAM sites. The first of these units was equipped with the F-100F Super Saber, an aging design armed with four 20mm cannons and rockets and outfitted with the RHAW system. These aircraft arrived at Thai air bases in November 1965 and claimed its first destruction of a SAM site in December of the same year. The more common Wild Weasels were modified F-105F and F-105G aircraft, which began replacing the F-100s in the summer of 1966. The F-105s were armed with a single 20mm rotary-cannon, but more importantly with the AGM-45 “Shrike” anti-radiation missiles, which could home in on a SAM site’s radar and could be fired from outside SA-2 range. Navy aircraft also carried the “Shrike” for the same purpose. Later during the Vietnam conflict, the Air Force would introduce the AGM-78 Standard missile, an improvement of the Shrike; however, the Shrike remained in use as it was far cheaper than the new Standard missile.

Despite the improvements in detecting and counteracting the SA-2s, the Vietnamese persisted increasing their numbers and usage. In 1965, there had only been a single SAM battalion in operation- by the following year, there were 25. In 1967 there were 30, and it was estimated that there were 35-40 operating in 1968. The number of missile firings increased correspondingly as well. In the first 11 months of SA-2 operations, about 30 missiles were fired per month. Between July 1966-October 1967, the number of monthly launches increased to 270. In November 1967, between 590-740 SA-2s were fired, a record which stood until December 1972.[16] The operators of the SAM sites also became more clever about firing their SA-2s as American responses developed. Instead of keeping their radar on all the time, NVA operators would use radar to track the incoming aircraft to a distance of 25 miles from the site, then switch the radar off and calculate the time it would take the aircraft to close to within a mile of the site before switching the guidance radar on and launching the SA-2s.[17] SA-2 crews also resorted to optical aiming with their missiles, which rendered ECM pods useless but also greatly reduced the effectiveness of the SAM.

In general, as the Vietnam War progressed, the number of SA-2s required to shoot down a single American aircraft increased. In 1965, it took about 18 SA-2s to shoot down a single American plane. The following year, that number increased to 35. In 1967 it took 57 SA-2s to shoot down an American plane, and by 1968 it could take as many as 107 missiles to achieve a kill. Despite this drop in launch-to-kill ratio, American pilots maintained a healthy respect for this threat, as evidenced in numerous memoirs. F-105 pilot Colonel Jack Broughton’s book, “Thud Ridge”, recounts numerous run-ins with SA-2s during his tour from 1966-1967. In one passage, Broughton describes how one of the more experienced pilots was brought down by a SAM, along with the frustrations and being denied from bombing the offending launch sites.

“Our old head had bounced through the refueling sessions and managed to stick with his leader, but his wingman, who was not so fortunate. He got bounced off the tanker boom by a particularly rough piece of air and was never able to find the flight again in the murk, so number three went all the way into the target without the benefit of that wingman for mutual support. The Migs were there, but they made it in and number three beat the big guns over the target. Coming off the target at about 7,000 feet, Sam got him. Nobody saw a Sam and nobody called one, but we already had two guys down at the time and the beepers were squealing and things were moving fast. The first sign of trouble was a large rust-colored ball that enveloped his aircraft. Coming out of the ball, his aircraft appeared intact but he started a stable descent with his left win dipped slightly low. His only transmission was, “I gotta get out. I’ll see you guys.’ With that, he pulled that handles and we saw a chute and heard the beeper as he headed for Hanoi via nylon. The Sam site that got him didn’t have to be there. We let it be there. Why? As fighter pilots, none of us could understand or accept the decision to allow the Sams to move in and construct at will, but then fighter pilots must be different.”[18]

Another fighter pilot, eventual-Brigadier General Robin Olds, flew a tour in Vietnam as the commander of an F-4 Tactical Fighter Wing, as was fired on repeatedly by SA-2s over the course of his tour, remarking, “I had 22 shot at me, and the last one was as inspiring as the first.”[19] And despite the reduction in their effectiveness, they still were responsible for the loss of many US aircraft; during the period of October 1867- April 1968, between 115-128 US aircraft were lost to SA-2s.[20]

Perhaps the most successful period of SA-2 operations during the Vietnam War came near the end of American involvement during the conflict. In an effort he hoped would force the North Vietnamese back to the peace talks in Paris, President Richard Nixon ordered the bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong Harbor by B-52 strategic bombers. Over 200 of the bombers, flying from bases in Thailand and Guam formed the main impetus behind Operation Linebacker II. However, Air Force commanders made several mistakes when planning the operation; the bombers flew at 30,000 feet- an optimal range for SA-2s, they flew behind one another in trailing formations, and they generally used the same air corridors. As a result, SA-2 crews were able to volley fire into the bomber stream with little to stop them. Over the course of the eleven-day bombing campaign, over 1200 missiles were fired, shooting down 15 B-52s and damaging others beyond repair. Despite the losses, the B-52s were still able to seriously damage Hanoi’s infrastructure, while Hanoi had expended most of its SA-2s and was left vulnerable.[21] By the end of the Vietnam War, SA-2s had claimed several hundred aircraft and led the US to place much more emphasis on being able to deter missiles with electronic countermeasures, jamming, and suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) missions.

Outside of Vietnam, the SA-2 also saw extensive service and use with Egypt against Israel during the War of Attrition and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Egyptian SA-2s shot down several American-built Israeli Air Force aircraft with SA-2s during both conflicts. SA-2s saw use in various other conflicts as SAMs until the 1990s, by which time they were generally considered outdated and ineffective against more modern aircraft and countermeasures. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union began replacing the SA-2 in frontline usage with the S-300-series system, which had far greater range and capabilities. However, the SA-2 continues in use with many countries which have continued modifying the missile in an effort to ensure it remains a viable defense system. Oddly, the missile has also been adapted as a surface-to-surface ballistic missile in the Bosnian War and ongoing Yemeni Civil War, though its effectiveness in such a role must be questionable.

The SA-2 was the first combat-proven surface-to-air missile system. Building off of ideas initially envisioned in the Second World War and from early designs, the SA-2 became an iconic weapon of the Cold War, which drove further SAM development on both sides, and forced the US to increase its efforts in developing successful electronic warfare platforms. It was in part the development of such technologies which would allow US aircraft to experience such a degree of success over Iraq in 1991.

An Egyptian SA-2 transporter, pictured in the 1980s. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Sources

1. “V-75 SA-2 GUIDELINE HQ-1 / HQ-2 (Chinese Versions) Tayir as Sabah (Egyptian Versions).” V-750 SA-2 GUIDELINE - Russia / Soviet Nuclear Forces, 23 June 2000, fas.org/nuke/guide/russia/airdef/v-75.htm.

2. “SA-Guideline S-75 Dvina Desna Volchov Ground Air Defense Missile System.” Global Military Army Magazine Defence Security Industry Technology News Exhibition World Land Forces - Army Recognition, Army Recognition, 9 May 2020, www.armyrecognition.com/russia_russian_missile_system_vehicle_uk/sa-2_guideline_s-75_dvina_desna_volchov_ground_air_missile_system_technical_data_sheet_specification.html.

3. O'Connor, Sean. “Soviet/Russian SAM Site Configuration Part 1: S-25/SA-1, S-75/SA-2, S-125/SA-3 and S-200/SA-5.” Air Power Australia, 21 Dec. 2009, www.ausairpower.net/APA-Rus-SAM-Site-Configs-A.html.

4. Kopp, Carlo. Almaz S-75 Dvina/Desna/Volkhov Air Defence System / SA-2 Guideline / Зенитный Ракетный Комплекс С-75 Двина/Десна/Волхов, 3 July 2009, www.ausairpower.net/APA-S-75-Volkhov.html.

5. Leone, Dario. “60 Years Ago Today, the Surface-To-Air Missile Scored the First Ever Successful Shoot-Down of an Aircraft.” The Aviation Geek Club, 6 Mar. 2020, theaviationgeekclub.com/60-years-ago-today-the-surface-to-air-missile-scored-the-first-ever-successful-shoot-down-of-an-aircraft/.

6. History.com Editors. “U-2 Spy Incident.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/topics/cold-war/u2-spy-incident.

7. Carlson, Mark. “Operation Spring High: Thuds vs. SAMs.” HistoryNet, HistoryNet LLC, 23 Oct. 2019, www.historynet.com/operation-spring-high-thuds-vs-sams.htm

8. National Intelligence Estimate, Number 11-3-67: Soviet Strategic Air and Missile Defence, CIA, 1967, pp. 9–10. Declassified October 2005.

9. Correll, John T. “Take It Down! The Wild Weasels in Vietnam.” Air Force Magazine, Air Force Association, 1 July 2010, www.airforcemag.com/article/0710weasels/.

10. Freed, David. “The Missile Men of North Vietnam.” Air & Space Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, Dec. 2014, www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/missile-men-north-vietnam-180953375

11. IPS Correspondents. “BOSNIA-HERCEGOVINA: U.N. Pledges Support For Bangladeshis in Bihac.” BOSNIA-HERCEGOVINA: U.N. Pledges Support For Bangladeshis in Bihac | Inter Press Service, Inter-Press Service, 17 Nov. 1994, www.ipsnews.net/1994/11/bosnia-hercegovina-un-pledges-support-for-bangladeshis-in-bihac/.

12. Tillman, Barrett. “SAM SA-2: The Aviator's Real Enemy.” Flightjournal.com, Dec. 2014, www.flightjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/SAM-SA-2.pdf.

13. Broughton, Jack, and Hanson W. Baldwin. Thud Ridge. Crécy, 2006.

14. Werrell, Kenneth P. Archie, Flak, AAA and SAM: a Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense. Air University Press, 2005.

[1] https://fas.org/nuke/guide/russia/airdef/v-75.htm

[2] https://www.armyrecognition.com/russia_russian_missile_system_vehicle_uk/sa-2_guideline_s-75_dvina_desna_volchov_ground_air_missile_system_technical_data_sheet_specification.html

[3] http://www.ausairpower.net/APA-Rus-SAM-Site-Configs-A.html

[4] http://www.ausairpower.net/APA-Rus-SAM-Site-Configs-A.html

[5] https://theaviationgeekclub.com/60-years-ago-today-the-surface-to-air-missile-scored-the-first-ever-successful-shoot-down-of-an-aircraft/

[6] https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/u2-spy-incident

[7] https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/u2-spy-incident

[8] P.9, National Intelligence Estimate Number 11-3-67: “Soviet Strategic Air and Missile Defense.” CIA, 9 November 1967. Declassified October 2005.

[9] https://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/missile-men-north-vietnam-180953375/?page=1

[10] https://www.historynet.com/operation-spring-high-thuds-vs-sams.htm

[11] https://www.historynet.com/operation-spring-high-thuds-vs-sams.htm

[12] P.108- Archie, Flak, AAA, and SAM: A Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense.

[13] https://www.historynet.com/operation-spring-high-thuds-vs-sams.htm

[14] https://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/missile-men-north-vietnam-180953375/?page=2

[15] https://www.historynet.com/operation-spring-high-thuds-vs-sams.htm

[16] P.107- Archie, Flak, AAA, and SAM: A Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense.

[17] https://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/missile-men-north-vietnam-180953375/?page=2

[18] P.102- Thud Ridge

[19] “SAM SA-2: The Aviator’s Real Enemy”, p.56

[20] P.107- Archie, Flak, AAA and SAM: A Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense

[21] https://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/missile-men-north-vietnam-180953375/?page=3