Film Review: 1917

/

By Seth Marshall

Several years ago, in a film review for Hacksaw Ridge, I commented that that film had failed to distinguish itself from the larger group of contemporary war films and as a result could not be called a great film. Director Sam Mendes’ new film, 1917, is not just an example of what a great war film should be, it is an example of a great film in general.

Towards the end of 1916, both sides were reeling from a horrific year of war. Both the Germans and French had suffered massively at the cataclysmic battle that was Verdun, and the British had suffered appalling losses during the Somme offensive. Taking stock of their situation, the German General Staff concluded that their forces were overstretched. Their front lines bulged out in several positions, which meant that German forces had to defend more ground. This cost men, weapons, equipment, and resources, all things which the Germans had already stretched as far as they could since they were fighting on two fronts.

The solution that the General Staff came up with was a strategic withdrawal to a much shorter line with well-built defensive positions. The new line, dubbed the “Siegfried Line”, was eighty miles long and was the largest construction project during the First World War. 500,000 tons of rock and gravel, 100,000 tons of concrete, and 12,500 tons of barbed wire were incorporated in the new positions, which took four months to build.[1] Another part of the operation, now referred to as Operation Alberich, would be the near-total destruction of the countryside in between the old lines and the new ones. 200 villages were razed to the ground, with houses and other structures pulled to the ground, wells were poisoned, electric cables cut, railway lines ripped apart, and civilians forcibly evacuated.[2] The new operation was not entirely liked by all senior German commanders. Overall commander Erich Ludendorff had reservations about the plan, fearing that the operation would be bad for the morale of German soldiers. Ruprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria and commander of an Army Group, unfavorably compared Alberich to the destruction of the Rhineland Palatinate by King Louis XIV of France in the 17th Century, the effects of which still resonated in the German public.[3]

This map shows the extent of the withdrawal that the Germans carried out in the spring of 1917. Photo source: Smithsonian.

In spite of these high-placed doubts, preparations were carried out for the withdrawal. While reconnaissance planes were in heavy use by this point in the war, those which photographed the construction effort were apparently unsuccessful in revealing the scope of German machinations. The Allies did receive some information indicating that the Germans were preparing additional defenses, but they didn’t anticipate the exact purpose and were not prepared for just how extensive the withdrawal was or how much destruction the Germans had caused in the region. In mid-March 1917, Allied patrols began discovering that the Germans were gone. Haltingly at first, the Allies began probing the now vacant German positions. In an effort to further slow their progress, the Germans had left snipers, timed explosives, and booby troops throughout the abandoned terrain. While causing relatively few casualties, these obstacles slowed the Allied advance.

Ultimately, Operation Alberich was a successfully strategic withdrawal. The Germans were able to substantially shorten their lines, easing the strain which various salients had placed on their infantry and supply lines. The withdrawal also caught the Allies off guard, and they were unprepared for the shear havoc the Germans had wrought in the formerly occupied area. The new German line, known as the Siegfried Line to the Germans and as the Hindenburg Line to the Allies, would not be breached by Allied forces until the Hundred Days Offensive in August 1918.

It is against the backdrop of Alberich that the film is set. Lance Corporal William Schofield (George McKay), a veteran from the Somme offensive the previous year, and Lance Corporal Tom Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) are told to deliver a message to Colonel Mackenzie, the commander of the Second Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment. MacKenzie’s unit is situated along a portion of the line which is in contact with the new Hindenburg Line, though they don’t yet realize it. There, with the German defenses far stronger than expected, the Devons were scheduled to attack the following day. It is implied by the general giving the order that the entire battalion would suffer heavy casualties or be wiped out completely.

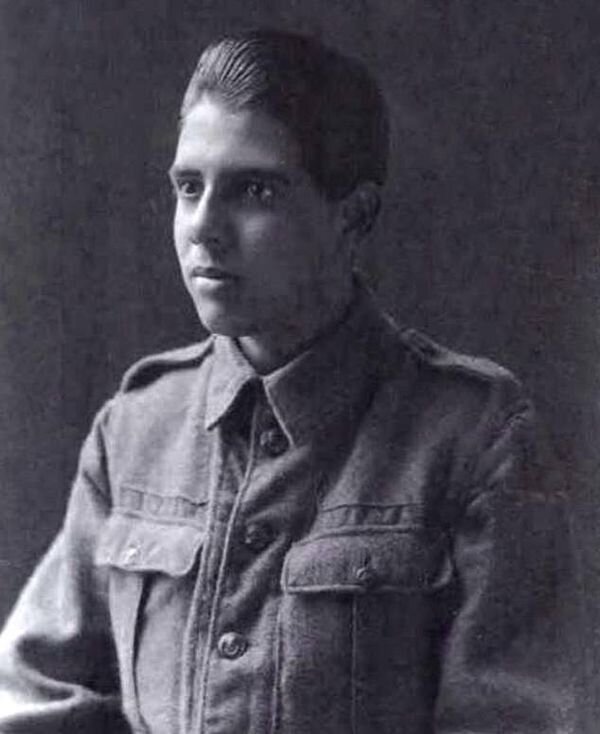

The film then follows the two lance corporals as they attempt to make their way to the Devons before they step off into the attack. Without giving too much away, they encounter numerous obstacles to achieving their objective. What follows is very reminiscent of the kind of individual stories told by veterans in the years after the war. This is probably no accident, since director Sam Mendes based the screenplay on the experiences of his grandfather, Alfred Mendes.[4] Through most of the movie, both characters are on their own, isolated from their unit or neighboring units. The viewer is pulled into the war on an individual scale with the two soldiers- we only get brief glimpses of the larger strategic picture. We see much of the struggles of daily life for soldiers living in the trenches- mud, rats, unburied corpses, barbed wire, sleeping in small earthen shelters, and more. The narrative-feel of the film is enhanced by the unbroken take style of the film, which again feels similar to reading an account of the events written by a veteran soon after the war. The sense of being in a in a personal account is made all the more real to the audience when Schofield is knocked unconscious and the camera cuts to black. When he comes to, the day has been replaced by night, with burning fires and hanging flares providing scant illumination. 1917 is a profoundly personal film, focusing on the struggles of Schofield and Blake and other soldiers at ground level in the conflict.

Director Sam Mendes based his screenplay in part on the stories told to him by his grandfather, Alfred Mendes, who served on the Western Front in 1917 in the 1st Rifle Brigade. Photo: Smithsonian.

In addition to a captivating if fictitious storyline, 1917 is a visually stunning film. Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins worked to make the movie feel more like a story by smoothing the film into what seems like an almost unbroken cut. The success of this technique is a tremendous accomplishment in an of itself, since the filmmakers had to make absolutely sure that every different shot they filmed had continuity with the scene prior. Contending with English weather made the task more difficult, as the weather can obviously not be controlled. Despite the effort placed into giving the film the single-shot feel, attention to detail was not sacrificed, from the godawful living conditions portrayed in the trenches, the destroyed buildings in the city, and the toxic lunar landscape that is no-man’s land. One of the more memorable scenes from my perspective occurs relatively early in the film. After cutting his hand on some barbed wire, Schofield slips while moving through a shell crater and instinctively puts out his cut hand to steady himself, only for it to go straight through the chest of corpse he hadn’t seen. It’s a small little detail which speaks volumes about the horrible nature of the First World War.

1917 is a tremendous film. With a storyline that feels like it’s been pulled straight from the report or memoir of the soldier who was there, 1917 is an intimate affair which engrosses the audience with its attention to detail and believable characters. Easily one of the best movies of 2019, it is also the best war film in years. Not just for the reader interested in military history, but also the movie fanatic, 1917 is a must-see.

Sources

1. Lang, Kevin. “1917 Was Inspired by a True Story Sam Mendes' Grandfather Told Him.” HistoryvsHollywood.com, History vs. Hollywood, 3 Jan. 2020, www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/1917/.

2. Showalter, Dennis. “Operation Alberich.” 1914 1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Freie Universtiaet Berlin, 16 Dec. 2016, encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/operation_alberich?fbclid=IwAR3FPS4Y2M2lCm8iCgjfQVmPpzrEoSXO7mGUPWxGvZwtRkqQ28spchka12M.

[1] https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/operation_alberich?fbclid=IwAR3FPS4Y2M2lCm8iCgjfQVmPpzrEoSXO7mGUPWxGvZwtRkqQ28spchka12M

[2] https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/operation_alberich?fbclid=IwAR3FPS4Y2M2lCm8iCgjfQVmPpzrEoSXO7mGUPWxGvZwtRkqQ28spchka12M

[3] https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/operation_alberich?fbclid=IwAR3FPS4Y2M2lCm8iCgjfQVmPpzrEoSXO7mGUPWxGvZwtRkqQ28spchka12M

[4] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/1917/