Tools of War: The Messerschmitt Me-109

/A restored Bf-109G-6. Photo source: Wikipedia.

In the mid-1930s, the Messerschmidt firm produced the Me-109, at the time one of the most advanced fighters in service anywhere in the world. Ten years later in 1945, the Me-109 remained in service with the Luftwaffe and had become the most prolific fighter ever built by any air force in military history, and was the aircraft flown by many of the Luftwaffe’s successful aces.

By Seth Marshall

There were many iconic fighter aircraft which emerged from the Second World War- the North American P-51 Mustang, the Supermarine Spitfire, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, and the Yakovlev Yak-9. Among this list must be included the Messerschmitt Me-109, which would become the most-produced fighter in the history of military aviation. First flown in 1935, the aircraft would remain in production in Germany until the end of the war in 1945, and post-war variants would continue to be built for years in both Spain and Czechoslovakia. The Luftwaffe’s most successful aces flew the small fighter, accumulating hundreds of aerial victories. In spite of this history, the Me-109 had its beginnings in a small passenger aircraft.

The Messerschmitt company had been around in some form since 1916, though it operated under other names prior to the late 1930s. In 1927, Willi Messerschmitt joined the company, at the time called Bayerische Flugzeugwerke Allgemeine Gesellschaft (BFW) as its chief designer. Unfortunately, several early designs failed miserably, and by 1931 the company was in bankruptcy. Two years later, the company was revived and work began on a low-wing monoplane design capable of carrying four passengers and equipped with retractable landing gear. The design was completed and first flown in 1934 as the Bf-108 Taifun, and attracted attention at international flying events.[1] Before the Bf-108 had made its first flight, the Messerschmitt firm learned that a specification was about to be issued for a new fighter aircraft by the Reichsluftfarhtministerium (RLM). Among the competitors, aside from BFW, were Arado, Focke-Wulf and Heinkel, all of which were more established companies.[2] The new aircraft was to be powered by a Junkers Jumo 210 engine and be capable of reaching at least 280 mph.[3] However, from the outset of the project, there was little to suggest that BFW would win the contract, since Erhard Milch, the head of the RLM, had a bitter rivalry with Messerschmitt. Still work progressed- the design team, lead by Messerschmitt, used many of the features which had been in place on the Bf-108. The new fighter, in addition to possessing the low wing and retractable landing gear which its predecessor had, featured an enclosed cockpit, all-metal construction, flush rivets, leading-edge wing slats, and trailing-edge wing flaps.[4]

One of the prototype Bf-109s exhibiting the large radiator beneath the nose, characteristic of early 109s. Photo source: Wikipedia.

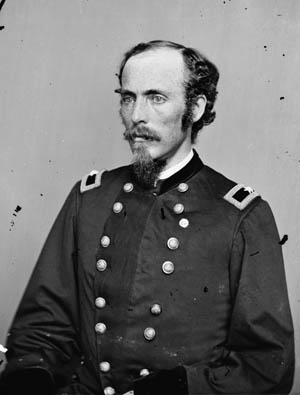

Wilhelm ‘Willi’ Emil Messerschmitt was born in 1898 in Frankfurt am Main. He got his start designing gliders in World War I and started his own aircraft firm in the 1920s. His 1934 design of the 109 was his culminating achievement in aircraft design. He would die in 1978 at the age of 80. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The Focke-Wulf FW 159, the nearest competitor to the Bf-109. The design was ill-fated- after a crash in 1935, the type lost a competition with the Bf 109. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The prototype Bf-109 (known as the Bf-109V-1) was completed in August 1935. Owing to a shortage of Junkers Jumo engines at the time, the first Bf-109 was fitted with a Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine, the same engine which powered the Stuka. The first flight of the new aircraft occurred September at Rechlin, the RLM’s testing center. Shortly after the first flight, a second prototype was built with the Junkers engine and strengthened landing gear. Flight testing revealed an aircraft which performed above the standards outlined in the RLM specification, but it did suffer from high wing-loading, which limited its maneuverability at lower altitudes. The new fighter proved much more promising than two of its competitors, the Arado Ar-80 and Focke-Wulf FW-159. Ten pre-production versions, designated Bf-109B-0s, were immediately ordered.[5] At the same time, ten examples of the remaining competing aircraft, the Heinkel He 112 were ordered.[6] This order was later followed with thirty production models, the first of which were delivered in February 1937. These production variants had a 680-hp Jumo 210D engine, two machine guns, and a two-bladed propeller.[7]

At the same time that the Bf-109B was being developed, the Spanish Civil War broke out. In November, the Condor Legion was formed from volunteers from the Luftwaffe and dispatched to Spain in support of Francisco Franco’s Nationalists. However, the Soviet Union had also dispatched their own pilots and aircraft to support Republican forces, and Condor Legion pilots quickly discovered that their Heinkel He-51 biplane fighters were entirely outclassed by Soviet-supplied Polikarpov I-15 biplane and I-16 monoplane fighters. As a stopgap measure, the fourth prototype Bf-109 was rushed to Spain, quickly followed by the first three Bf-109B-1s in early 1937. The newer B-1s could reach 292 mph and had a ceiling of 30,000ft.[8] The first Bf-109 unit to be formed was the second Staffel of Jagdgruppe 88 (2.J/88), commanded by Gunther Lutzow.[9] The pilots of 2.J/88 found that the arrangement of the new fighter’s landing gear caused accidents on take-off and landing- this was an issue which would never be solved during the Bf-109’s operational life. However, it was found that by using the rudder to compensate for the fighter’s flaws offered a fix, and preparations continued for combat missions. The first operation occurred on July 8, 1937 over the Brunete salient.[10] The first kills scored by the aircraft were made one the first mission- Leutnant Rolf Pingel and Unteroffizier Guido Hӧness each shot down a Soviet-suppplied Tupolev SB-2 bomber. On July 12th, Hӧness shot down two Aero A-101s, Pingel shot down another SB-2 and an I-16, while Feldwebels Peter Boddem and Adolf Buhl each shot down a I-16. The same day, Hӧness was shot down and killed, becoming the first Bf-109 pilot to be killed in combat.[11] In time, the Condor Legion was equipped with some 20 Bf-109s.[12] Legion pilots began developing tactics which would prove to be crucial to early Luftwaffe successes in World War II. Spearheaded by Werner Mӧlders, Legion pilots began flying in formations known as the Rotte, Schwarm, and Staffel.[13] The Rotte was the most basic fighter formation, composed of two aircraft , with the wingman positioned at a 45-degree angle to the rear of the leader. While the lead aircraft would look out for enemy aircraft ahead, the wingman would keep a watch for enemy aircraft to the rear.[14] The Schwarm was two Rotte put together, with one Rotte arrayed slightly ahead other and staggered the opposite direction. The Schwarm would eventually be adapted by both the RAF and the USAAF during the war. These formations, larger and more spaced out than previous ones in air forces and allowed for greater flexibility in operations.[15] These tactics proved their success over Spain- between July and August 1938, Condor Legion fighters shot down 29 Republican aircraft.[16]

One of the first 109s dispatched to Spain, wearing its Kondor Legion markings. Photo source: Wikipedia.

As combat over Spain continued, Messerschmitt proceeded with further development of the fighter. In the spring of 1938, the Bf-109C-1 arrived in Spain, equipped with a fuel-injected Jumo 210Ga engine and four machine guns. A later modification included a fifth machine gun mounted in the engine, firing through the propeller hub. In August 1938, the first Bf-109Ds began to arrive in Spain- these new aircraft combined the carburetor-equipped Jumo 210Da engine of the B-1 with the four-gun armament of the C-1.[17] A series of updates would result in the Bf-109E-1- the Jumo engine was replaced with fuel-injected 1,100hp Daimler-Benz DB 601A engines, which caused the deletion of the large radiator at the front of the aircraft and installation of small radiators beneath both wings.[18] The new engine gave a top speed of 354 mph and a combat radius of approximately 365 miles.[19] Four machine guns were now standard- two MG 17 7.92mm machine guns in the nose, and one in each wing. The two-bladed propeller was replaced with a three-bladed variable pitch propeller.[20] All of these changes improved the 109’s performance- when the new “Emil” began reaching units in the late summer of 1939, it was arguably the best fighter aircraft in the world.

A Bf-109 undergoing maintentenace during late 1939 or early 1940. Judging by its appearance, this is a Bf-109E-1. Photo source: Wikipedia.

When Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, the Luftwaffe had on hand 946 operational Bf-109s of all types. The 109 quickly proved itself superior to anything the Polish Air Force had- its most modern aircraft was the PZL P. 11, a parasol-wing fighter which was at one time in the mid-1930s considered one of the most modern fighters. Now, however, it was hopelessly outclassed by the Bf-109. Months later, the 109 again demonstrated its superiority against Denmark, then against the Low Countries and France. The Dutch Air Force had the Fokker D. XXI, a low-wing monoplane with fixed landing gear, while the French had the Dewoitine D.520 and the Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, both of which were low-wing monoplanes with retractable landing gear. Both the Fokker and Morane-Saulnier were outclassed by the 109- only the Dewoitine offered a relatively even chance against the 109, but it carried fewer weapons and was considered a difficult aircraft to fly. However, near the end of the French campaign, when the BEF was evacuating from Dunkirk, 109 pilots began encountering Royal Air Force (RAF) units flying Spitfires. The Spitfire was to be the first truly formidable opponent that Luftwaffe fighter pilots would encounter. A number of Messerschmitts were lost over Dunkirk at the hands of Spitfires, and more Luftwaffe aircraft were shot down because the airfields which 109s were flying from were still in eastern France and western Germany, which seriously limited the amount of time the fighters could spend above the beaches.[21] The Dunkirk evacuation ended on June 4th, and three weeks later France fell. The Bf-109’s next challenge would come over the English Channel and southern England.

At the start of the Battle of Britain, Luftflotte 2 and 3 reported having a combined total of 809 single-engine fighters available, with 656 serviceable- the vast majority of these were Bf-109E-1s and Bf-109E-4s (a new version which substituted each machine gun in the wings with a 20mm cannon). Luftflotte 5 reported that of the 84 single-engine fighters in its inventory, 69 were serviceable.[22] Facing this force was the RAF’s Fighter Command, which on July 10th reported having 902 single-engine fighters, of which 570 were operational- this figure included 344 Hurricanes and 226 Spitfires.[23] Both of these aircraft represented significant opposition to the supremacy of the 109.

A Rotte of Bf-109E-4s from JG 52, possibly patrolling over the English Channel, probably during the summer of 1940. Painting by Robert Taylor.

The Hurricane, which first flew in 1935, was armed with eight .303 caliber machine guns, featured metal wings and a fuselage which featured canvas stretched over a metal-tube frame. The Hurricane Mk II, which was the primary variant in service at the time, was powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin which could push the aircraft to a maximum speed of 335mph and reach a maximum altitude of 41,000 feet.[24] The Hurricane unsuccessfully fought against the Luftwaffe in France- Hurricane pilots were able to inflict losses but were overwhelmed and sustained tremendous losses. Nonetheless, the aircraft was considered relatively simple to fly and more forgiving than its sleeker cousin, the Spitfire. The Spitfire first flew in the spring of 1936 and featured a monocoque construction (all-metal stressed skin, providing a sleeker and more aerodynamic profile). Spitfires were also powered by the Merlin engine- in the Mk 1, the primary variant during the Battle of Britain, the maximum speed attainable was 355mph. Like the Hurricane, it was armed with eight .303 caliber machine guns.[25] Both of these aircraft could outturn the Bf-109- in the case of the Spitfire, it could keep up with the German fighter. The 109 had the advantage of being able to out-climb and out-dive the RAF fighters, and it packed greater firepower.[26]

There were other factors which contributed to this clash of fighters. For instance, the 109 was at a range disadvantage- with a combat range of about 400 miles, 109 pilots only had time for about 20 minutes of combat over England before having to turn towards home.[27] Additionally, the British had constructed the world’s first integrated air defense system, with rings of radar stations and observer posts feeding reports on formations’ numbers, altitude, and heading to a series of command posts, which would then relay information to intercept stations, who in turn would guide RAF fighter formations to intercept the Germans. And unlike their German counterparts, if an RAF pilot was shot down and bailed out, he would quickly be returned to his unit to return to battle. Against these clear RAF advantages, the Germans had months, in some cases years, of experience in their aircraft under combat conditions. They could also draw on more tactically viable formations than the British.

Still, when German dive bombers began attacking Channel convoys in July, RAF pilots were usually able to inflict some losses on the 109s. On July 25th, Bf-109s from II. and III./JG 26, I. and II./JG 51 and III./JG 52 escorted a large formation of Stukas to attack shipping in the Channel- they were attacked by 20 fighters from 54, 65 and 610 Squadrons, which were able to shoot down two Stukas and two 109s- in turn, the Germans shot down five fighters.[28] On August 8th, JG 27 lost 10 Bf-109s with four pilots killed, claiming to have shot down 13 RAF fighters.[29] In some cases, the Luftwaffe pilots were able to turn the tables on the RAF. On July 19th, twenty 109s attacked 9 Bolton-Paul Defiants from 141 Squadron. The Defiant, an odd two-crew aircraft with a four-gun turret mounted behind the cockpit and no forward-firing armament, was proved to be ill-suited to daylight missions against the Luftwaffe- five Defiants were shot down and sixth crash-landed, while a single Bf-109 was lost in return.[30] On July 28th, Adolf Galland was leading a fighter sweep with Bf-109s from III./JG 26 when he attacked 12 Spitfires from 74 Squadron. The Spitfires had been expecting to find a large bomber formation- Galland’s attack from above cost the RAF three Spitfires, with no 109s lost.[31] Galland would go on to become one of the first Luftwaffe aces to surpass 100 kills, and would eventually become a General and Inspector of Fighters. In spite of some successes, the Luftwaffe fighter pilots sustained a steady rate of attrition which only worsened in August and September. On September 2nd, one of the most intense days during the battle, 21 Bf-109s were shot down and another four returned with serious damage.[32] Bf-109 units sustained heavy losses through the battle. During the entire month of September, JG 27 lost 27 aircraft- the authorized strength of a Geschwader was 94 planes.[33],[34] Fighter missions did not stop with the beginning of the Blitz or with the cancellation of Operational Sea Lion. In a foolish attempt to keep up the pressure on the British while the bombers were shifted to nighttime missions, many fighter units were ordered to fly fighter-bomber sorties over England, carrying one bomb on a centerline rack. The first of these missions occurred on October 2nd.[35] Ill-suited for these raids, the 109s were unwieldy and vulnerable with their bomb loads, and pilots often dropped their bombs when attacked by RAF fighters. Still, the fighter-bomber offensive continued until the end of October.

When the battle was finally declared over at the end of October 1940, Bf-109 pilots had met their first setback. They had claimed 1,752 aircraft shot down in exchange for 534 109s lost-however, actual RAF losses were significantly lower- approximately 1,050 were believed to have been shot down by all Luftwaffe fighters (including both Bf-109s and Bf-110s).[36]

Hans Joachim-Marseille was one of the more remarkable pilots in the Luftwaffe who scored the bulk of his 158 victories while flying over Africa. He began his combat career during the Battle of Britain, where he developed a penchant for insubordination. Reassigned to Africa in April 1941, he quickly began accumulating aerial victories. He was only 23 at the time of his death in September 1942, when died trying to bail out of his disabled aircraft- he impacted the tail surface of the aircraft, likely knocking him unconscious or killing him- he then fell to earth. Photo source: Wikipedia.

One of several foreign air forces that the Bf-109 served with was the Finnish Air Force- this Bf-109G-2 is warming up its engine in preparation for a mission. Photo source: Wikipedia.

Ilmari Juutilainen was the highest-scoring Finnish Air Force ace during the Second World War. Scoring his first several victories in a Fokker, then 36 kills in a Brewster Buffalo, Juutilainen would go on to shoot down 58 aircraft in a Bf-109. He died in 1999 at the age of 85. Photo source: Wikipedia.

Despite losses, Luftwaffe operations would continue along the English Channel with varying degrees of intensity through the fall of 1940 and into the spring of 1941, until most units were transferred to the eastern front or to Africa. During this time, a new version of the Bf-109 was developed and introduced into service-the Bf-109F. This new 109 featured several structural changes which strengthened the airframe and streamlined the shape- the nose and wingtips were rounded to improve aerodynamic performance. An improved engine, the 1350-horsepower Daimler-Benz 601E was provided, and the armament was shifted to two-cowling mounted 7.9mm machine guns and one 20mm cannon firing through the propeller shaft.[37] Coming into service in large numbers beginning in late 1940 and early 1941, the Bf-109F-1 and Bf-109F-4 would see extensive service in North Africa and during Operation Barbarossa beginning in June 1941.

When the invasion of the Soviet Union began on June 22, 1941, the Luftwaffe had on hand over 480 fighters and fighter-bombers to fly sorties- many of these aircraft flew between five to eight sorties on the first day alone.[38] For 109 pilots, their goal was the destruction of the Red Air Force in the air and on the ground, and escorting bombers to their targets. After nearly two years at war plus the experiences gained in Spain, Luftwaffe fighter pilots were seasoned and well-experienced flyers; many of them were aces with scores of kills to their credit already. The pilots of the Red Air Force during the opening stages of the war were more often than not relatively new and unexperienced pilots who suffered terribly at the hands of their German adversaries. On the first day of the campaign, Soviet bombers from the 40th High-Speed Bomber Aviation Regiment attempted to bomb German airfields in East Prussia- Me-109 pilots intercepted them and shot down 20 without loss.[39] Even large Soviet raids were met with disaster- on July 5th, a large bomber formation set out to bomb German airfields- when they were detected by German raider, 140 Me 109s from JG 52 and JG 3 took off and intercepted them- the Germans claimed to have shot down 120 Soviet aircraft.[40] On July 9th, 27 Soviet bombers attacked an airfield where JG 3 was stationed- commanded by Major Gunther Lutzow, JG 3 scrambled and attacked the 27 bombers- in 15 minutes, all of the bombers had been massacred.[41]

These months were perhaps the apex of the Bf-109’s career, during which the highest kill rates were achieved. Through the summer and early fall of 1941, Jagdgruppe kill scores skyrocketed. On August 30th, JG 3 claimed its 1,000th kill on the eastern front.[42] Between June and November 1941, JG 54 claimed 1,123 aircraft shot down.[43] However, by late summer 1941, the same aspect of the war which was proving increasingly difficult to overcome was also plaguing Luftwaffe units- there was simply too much airspace to cover with too few aircraft. An example of this was the case of JG 3- on July 28th, JG 3 move to an airfield at Belaya Tserkov to provide air support above the Ulman pocket- of its 125 Bf-109s, on half were flyable.[44] Additionally, while the Germans were steadily racking up incredible amounts of kills, they were also suffering from attrition. While JG 54 had claimed over 1100 aircraft shot down from June-November, they had lost 37 out of their 112 pilots killed or missing during the same period.[45] In the wake of the failure of Operation Taifun to take Moscow and the subsequent retreat, some units were transferred to other fronts, particularly Africa, to support operations in other theaters. By then, Bf-109 units had suffered tremendous casualties and losses in aircraft.

1942 saw the development and introduction of the most numerous variant of the Bf-109- the ‘Gustav’ (Bf-109G). This aircraft was first rolled off production lines in March 1942. Armament for the Bf-109G-1 consisted of a single 20mm MG 151 cannon firing through the propeller hub, and two 7.9mm MG 17 machine guns mounted in the cowling. Notably, the first ‘Gustav’ variant was also the first 109 to feature a pressurized cockpit. Multiple versions of the Gustav were ultimately produced, with different armaments and engines. In the end, over 24,000 Gustavs were built.[46] The Gustav 109 would be the first which American bomber pilots would face in large numbers in the skies above Western Europe.

Bf-109G-6s under construction- the G-6 variant was the most numerous of the Gustavs. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The arrival of American bombers in large numbers starting in August 1942 was not something that the Luftwaffe was prepared for. At first, only JG 2 and JG 26 were in place to defend the Reich.[47] The reason for this was simple- the RAF had been mounting night bombing raids ever since its disastrous experiment with daylight bombing in October 1939. As a result, it was thought that two Jagdgruppen would be sufficient to parry RAF fighter sweeps along the English Channel. However, by the end of August 1942, the USAAF had 3 Bomb Groups from the 8th Air Force in England, numbering 119 B-17s. These heavy bombers were much different that what the Luftwaffe had previously faced. When the RAF mounted its few daylight raids, the best it could muster was the relatively lightly armed Vickers Wellington, which had just two machine gun turrets armed with .303 caliber machine guns. The B-17 had three turrets with twin .50 caliber machine guns, and another seven .50 calibers in single mounts, making for a far heavier volume of fire for Bf-109 pilots to hazard. At first, Luftwaffe pilots attempted to attack from the rear of the heavy bombers, which they called Viermots (in reference to their four motors). The B-17s had been designed with this in mind, and had a tail turret as well as other guns which could cover the rear sector. By the end of the year however, Luftwaffe pilots had realized that the B-17s were vulnerable to head-on attacks. Based on early experiences, Luftwaffe Inspector of Fighters Adolf Galland issued this document to his pilots:

“A. The attack from the rear against a four-engined bomber formation promises little success and almost always brings losses. If an attack from the rear must be carried out though, it should be done from above or below, and the fuel tanks and engines should be the aiming points.

B. The attack from the side can be effective, but it requires thorough training and good gunnery.

C. The attack from the front, front high, or front low, all with low speed, is the most effective of all. Flying ability, good aiming and closing up to the shortest possible ranges are the prerequisites for success.

Basically, the strongest weapon is the massed and repeated attack by an entire fighter formation. In such cases, the defensive fire can be weakened and the bomber formation broken up.”[48]

A formation of fighters would fly on a parallel track to the bombers, overtake them by several kilometers, then turn in front of the bomber box and attack head-on. It was determined that it would take some 20 hits from a MG 151 cannon to bring down a B-17. However, tail attacks remained in use by Luftwaffe pilots who were newer and not skilled enough to attack from the front.[49] Generally, once the fighters had turned for their attacks, they closed to 800-400 meters before opening fire.[50]

A Bf-109G from JG 27, armed with MG 151 cannons to combat heavy bombers. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The increasing number of bomber raids on German territory by heavy bombers resulted in modifications to Bf-109Gs to make them more effective against the heavies. Many had one 20mm cannon mounted in a pod under each wing. These cannons negated the 109’s abilities in a dogfight with Allied fighters, but they proved effective against the bombers. Later, Bf-109Gs began carrying aerial rockets, which could be fired a longer ranges. These weapons were modified from the ground-based Nebelwerfer rocket- their accuracy was poor in general, but they had the potential to achieve the secondary objective of breaking up a formation, which in turn opened bombers up to more fighter attacks. Through 1943 and into 1944, more fighter units were pulled away from the Eastern Front to take up the mission of homeland defense.

German pilots gained a certain respect for the bomber formations and their massed defensive fire. Franz Stigler, a Bf-109 pilot with JG 27 in the Mediterranean, shot down 28 Allied aircraft, including 5 heavy bombers:

“The B-17s took a lot more punishment. It was terrifying. I saw them in cases with their tail fins torn in half, elevators missing, tail gun sections literally shot to pieces, ripped away, but still they flew. We found them a lot harder to bring down the Liberators. The Liberators sometimes went up in flames right in front of you. Attacking bombers became a very mechanical, impersonal kind of warfare- one machine against another. That’s why I always tried to count the parachutes. If you saw eight, nine or ten chutes come out safely, then you knew it was okay, you felt better about it. When you flew through a formation, the B-17s couldn’t miss you. If they did something was wrong. I never came back from attacking bombers without a hole somewhere in my aircraft.”[51]

As a measure of how effective the gunners on the bombers could be against the fighters, on one of the infamous Schweinfurt missions when the 8th Air Force lost 60 bombers shot down, the Luftwaffe lost 31 fighters shot down, 12 damaged so badly that they were written off, and 24 damaged. This figure represented 3.4-4% of the fighter strength in Western Europe.[52]

Meanwhile on the Eastern Front, fighter units continued to rack up against the Red Air Force but losing a steady amount of aircraft and pilots. Still, the most successful fighter pilots in history flew many if not all of their missions along this front. Erich Hartmann, who entered the Luftwaffe at just 20 years old, eventually scored 352 victories while flying the Bf-109. All but seven of those victories were made against Soviet aircraft. Gerhard Barkhorn, another Bf-109 pilot, shot down 301 aircraft during the war. Over 100 Luftwaffe pilots would be credited with 100 or more aerial victories- most of these pilots flew the Bf-109 at least for part of their flying career- many flew only the 109. Other Axis countries flew the Bf-109 with success as well. Finland operated many Bf-109Gs, as did Romania, Hungary, and Italy. The most successful non-Luftwaffe Bf-109 pilot was Finnish pilot Eino Ilmari Juutilanainen, who scored many of his 94 victories flying the 109.[53]

Erich Hartmann, nicknamed ‘Bubi’ for his youthful appearance, was the highest-scoring Bf-109 pilot of the war and the highest-scoring fighter ace in military history with 352 kills. What was perhaps most impressive about this figure is that he did not begin flying combat missions until November 1942. After being held as a prisoner by the Russians until 1955, Hartmann would later go on to serve as an officer in the postwar Luftwaffe. He died in 1991 at age 70. Photo source: Wikipedia.

By spring 1944, the Bf-109’s days of air dominance on any front were gone. In the West, the US Army Air Forces had introduced the P-51 Mustang, a fighter with superior performance and the range to escort the heavy bombers all the way to the target. Luftwaffe losses drastically increased during the first six months of 1944- by the time of D-Day, air superiority had been claimed by the Allies. In the East, the Red Air Force vastly outnumbered the hopelessly overwhelmed and overstretched Luftwaffe. Still, Bf-109 production continued, even though many factories were now targeted by bombers- in fact, production reached its peak in 1944 with 14,212 109s built.[54] The final production version of the fighter was the Bf-109K. It was powered by a 1,550-horsepower Daimler-Benz 605 engine, and was armed with one 30mm cannon firing through the propeller hub, and two 15mm MG151 cannons mounted in the cowling. This final 109 version could reach a top speed of 452 mph.[55] The Bf-109K was destined to see its first combat during Operation Bodenplatte, a final disastrous attempt by the Luftwaffe to destroy Allied aircraft on continental Europe on New Year’s Day, 1945. When the war had finally ended in Europe in May 1945 and production had finally come to an end, over 33,000 had been built.[56]

Despite the end of the war though, the 109’s career had not ended. Many 109s had been delivered to Spain, where they continued to serve after the war. The Hispano Aviacon company began installing their own 1300-horsepower engines into Bf-109G fuselages, then began building its own whole aircraft. The final version of the Hispano HA-1112 (its designation) was equipped, rather ironically, with a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine- the same engine which had powered the 109’s former foes, the Spitfire and P-51 Mustang. The Spanish aircraft served well into the 1960s. Czechoslavkia was another country which produced its own version of the 109 following the war. Originally intended to built aircraft for the Luftwaffe, the S-199 and CS-199 (as they were referred to by the Czech Air Force) were equipped with a Junkers Jumo engine and unwieldy paddle-bladed propeller, which gave the aircraft very difficult handling characteristics. In 1948, a small number of these aircraft were sold to the fledgling nation of Israel, where they were immediately pressed into service in spite of the problems. Lou Lenart, a former US Marine Corsair pilot flying for the Israelis, said of the S-199, it was “probably the worst aircraft that I have ever had the misfortune to fly… you had that monstrous propeller and you had torque and no rudder trim."[57] In spite of this, the S-199s served for a year before being replaced by Spitfires. The Czech Air Force would continue to fly them until the late 1950s.[58]

The Bf-109 was the most prolific fighter aircraft ever produced. Despite the age of the design, it continued to serve in every area of the European and Mediterranean theaters. For Allied pilots, it became a respected and at times feared opponent, the mount of the Luftwaffe’s experten. In the area of military aviation, it remains one the greatest fighter designs produced.

A restored Bf-109E-4, pictured at the 2008 Thunder Over Michigan Airshow. Photo source: Author.

Sources

1. Bergstrom, Christer. Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited. Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC, 2015.

2. Brookes, Andrew. Air War Over Russia. Ian Allan Publishing, 2003.

3. Corum, James S. The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940. University Press of Kansas, 1997.

4. Forsyth, Robert. Luftwaffe Viermot Aces 1942-45. OSPREY Publishing, 2011.

5. Gunston, Bill. The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II. Greenwich, 2005.

6. Guttman, Jon. “Messerschmitt Me-109.” HistoryNet, HistoryNet, 2006, www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm.

7. McNab, Chris. Order of Battle: German Luftwaffe in World War II. Amber Books, 2009.

8. Sherman, Stephen. “Messerschmitt Bf 109.” Messerschmitt Bf 109 (Me 109) - History and Pictures of German WW2 Fighter Plane, Acepilots.com, July 2003, acepilots.com/german/bf109.html.

9. Wood, Derek, and Derek D. Dempster. The Narrow Margin: the Battle of Britain & the Rise of Air Power, 1930-1949. Penn & Sword Military Classics, 2003.

[1] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm 1/1/2019

[2] http://acepilots.com/german/bf109.html 10/15/18

[3] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[4] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[5] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[6] P.10- The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain & The Rise of Air Power, 1930-1949

[7] http://acepilots.com/german/bf109.html

[8] P.192- The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940

[9] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[10] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[11] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[12] P.202- The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940

[13] P.207- The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940

[14] P.12- Order of Battle: German Luftwaffe in World War II

[15] P.44- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[16] P.207- The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940

[17] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[18] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[19] P.218- The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II

[20] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[21] P.38- Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe, 1933-1945

[22] P.138- The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain & the Rise of Air Power 1930-1949

[23] Battle of Britain- Fighter Command- Operational Aircraft and Crews, 26 October 1945. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

[24] P.42-44- The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II

[25] P.54- The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II

[26] P.273- The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain & the Rise of Air Power 1930-1949

[27] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109.htm

[28] P.85-86- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[29] P.93- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[30] P.137-The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain & The Rise of Air Power 1930-1949

[31] P.88-89- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[32] P.164- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[33] P.245-The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[34] P.14- Order of Battle: German Luftwaffe in World War II

[35] P.247- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[36] P.281-282- The Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited

[37] http://acepilots.com/german/bf109.html

[38] P.24- Air War Over Russia

[39] P.36- Air War Over Russia

[40] P.182- The Defeat of the Luftwaffe: The Eastern Front 1941-45, Strategy for Disaster

[41] P.36- Air War Over Russia

[42] P.52-Air War Over Russia

[43] P.62- Air War Over Russia

[44] P.50- Air War Over Russia

[45] P.62- Air War Over Russia

[46] http://acepilots.com/german/bf109.html

[47] P.7- Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-45

[48] P.14- Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-45

[49] P.15 Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-45

[50] P.24- Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-45

[51] P.30- Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-1945

[52] P.26- Luftwaffe Viermot Aces, 1942-45

[53] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109

[54] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109

[55] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109

[56] http://www.historynet.com/messerschmitt-me-109