Battlefield Visit: Franklin

/A post-war illustration of the Battle of Franklin made by the Kurz & Allison company. Photo: Wikipedia.

In late 1864, the situation for the Confederacy was bleak. In the north, Grant had been laying siege to Petersburg, where the Army of Northern Virginia was trapped. In Georgia, John Bell Hood’s Army of the Tennessee had failed to stop William Tecumseh Sherman from taking Atlanta. In an effort to lure Sherman away from the city, Hood launched an ill-advised offensive into Tennessee. In late November, near the town of Franklin, Hood’s army met with disaster.

By Seth Marshall

The Confederacy’s situation in September 1864 was indeed becoming untenable. Since June, Grant’s Army of the Potomac had had Lee bottled up at Petersburg. Sherman took Atlanta on September 2nd. Off the coast, the Union Navy had effectively blockaded the southern coast, cutting off nearly all trade and keeping nearly all of the South’s warships stuck in port. Desertion rates among the South’s armies were increasing, and the Confederacy’s economy was in ruins.

In was in this atmosphere of desperation that Lieutenant General John Bell Hood, the commander of the Army of the Tennessee, decided to mount his offensive into Tennessee. Hood had taken command of the army during the summer and had been in charge of defending Atlanta from Sherman. Though he had inflicted some tactical defeats on the tenacious Union general, he had ultimately failed to prevent the city from being taken. Believing that he could draw Sherman away from Atlanta, he decided that an offensive into Tennessee would lure Sherman into a position where Hood could seize a victory. Hood’s ultimate, highly-ambitious plan was to advance through Tennessee and Kentucky, recruiting additional soldiers as he went, before rendezvousing with Lee to break the siege at Petersburg.[1] This plan was extremely ambitious, and would be overseen by a man who was perhaps not the best to carry it out. John Bell Hood had been born in the small town of Owningsville, Kentucky in 1831. He successfully received an appointment to West Point in 1849, but struggled academically, finishing near the back of his class in 1853. He was assigned to a number of frontier posts through the 1850s and was once wounded by an arrow during a fight with Native Americans. When the Civil War broke out, Hood sided with the Confederacy and was appointed as a first lieutenant in a cavalry unit. He proved himself as a commander, participating in the Peninsula Campaign, the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam, Fredricksburg, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga. At Gettysburg, Hood had lost an arm leading his men in an assault on Little Round Top. He had wounded again three months later at Chickamauga, where he was wounded in the leg so badly that he’d had it amputated. Hood had been a capable division commander, but was not as able as an army commander. During the Atlanta campaign, Hood had shown himself willing to push his army to the point of extreme casualties.[2]

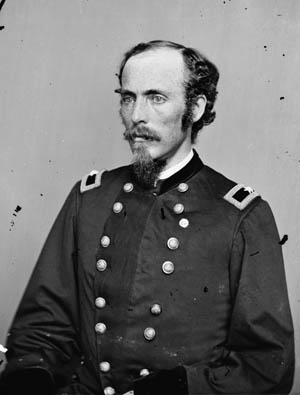

John Bell Hood began his military career with education at West Point. After graduating in 1853, Hood served in outposts in California and Texas as well as as a cavalry instructor at West Point. Curiously, Hood had graduated in the same class as his opposite number, John Schofield. Hood was considered an excellent division and brigade commander; as an officer in the Confederate army, Hood was wounded in the arm at Gettysburg and lost a leg at Chickamauga. He was appointed to command the Army of the Tennessee on July 18, 1864 at the age of 33, the youngest army commander on either side. Photo: Wikipedia.

John Schofield was born in New York in 1831. A graduate of the same West Point class as John Bell Hood, Schofield became an artillery officer serving in Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. He later served in Florida before returning to West Point as an instructor. Schofield rose steadily through the ranks after the outbreak of the war, attaining various commands in the Western Theater before being appointed commander of the Army of the Ohio on February 9, 1864. Photo: Wikipedia.

Hood’s offensive began in late September-early October with a series of raids in northern Georgia. With 39,000 men in his army, Hood’s Army of the Tennessee was one of the largest remaining armies in the Confederacy, and posed a viable threat to cities in the upper South. When Jefferson Davis inadvertently revealed Hood’s intentions in a speech in Richmond, Grant moved Major General George H. Thomas to Nashville to organize defenses. Hood continued sending raids into Tennessee until late November. Hood’s army finally crossed into Tennessee from Alabama on November 21st, after joining up with Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry force. For several days beginning on November 24th, Hood’s forces began skirmishing with Union forces at Columbia. Hood’s main enemy in the region was Major General John M. Schofield with his army of 30,000 men. In an effort to get into the rear of Schofield’s army, Hood detached Forrest’s cavalry force along with two corps of infantry on a flanking march while leaving behind a sizeable force across the river to tie down Schofield’s men. However, Schofield’s scouts saw this force moving and relayed the information to their commander.[3] Reluctant to believe the reports, Schofield didn’t send two divisions of infantry to hold the turnpike and crossroads at Spring Hill until the morning of November 29th.[4] Schofield’s men arrived just in time at the crossroads- not long after, the Southerners began to attempt to cut off Schofield’s army from the north by seizing the crossroads. However, a series of miscommunications throughout the day and culminating that night after Hood went to bed. As a result, Schofield was able to affect his withdrawal during the night, marching his men 12 miles to the north to Franklin.[5]

When Hood discovered what had happened the following morning, he was livid. He blamed his subordinate commanders for the failure to trap the Union force, writing:

“The best move in my career as a soldier, I was thus destined to behold come to naught. The discovery that the Army, after a forward march of one hundred and eighty miles, was still, seemingly, unwilling to accept battle unless under the protection of breastworks, caused me to experience grave concern. In my inmost heart I questioned whether or not I would ever succeed in eradicating this evil.”[6]

Movements during the Franklin-Nashville campaign leading up to the Battle of Franklin. Photo: Wikipedia.

Hood’s anger only increased when it was found that rising waters had destroyed the wagon bridge across the Harpeth River, forcing him to wait for a new one to be built. Meanwhile, Schofield had reached Franklin early in the morning. Instead of allowing his men to rest, he quickly ordered them to begin improving fortifications which had initially been dug the previous year. The main Union line, a trench with earthen barriers and wood fortifications, formed a rough crescent to the south of the town, with either flank butting up against the Harpeth River. In the middle of the line, a gap was left to allow still-arriving units to proceed forward. 70 yards behind the front line, a second line was constructed as a fall-back position.[7] Embrasures were cut in the defenses to allow guns to fire from cover- 60 guns in total. Many of these were emplaced on elevated terrain, giving them the ability to provide plunging fire against any foe marching across the fields from the south. Within the Union defenses a number of buildings stood, several belonging to the Carter family. Before the sun had risen, Brigadier General Jacob Cox, a temporary corps commander, woke Fountain Branch Carter. Carter lived in Franklin since 1830 when he built his small house and set to work as a farmer. He lived in the house with his wife Polly and several of their eight living children. Cox moved into Carter’s house, which occupied a small hill, and made it his headquarters. Carter meanwhile moved to the basement and took shelter with the Lotz family and several slaves, and would remain there until after the fighting had halted.

Still furious with his subordinates, Hood marched his men north as quickly as he could. Arriving south of Franklin in mid-afternoon, Hood ordered his commanders to assault the Union position with first reconnoitering the position. His junior commanders protested, which only caused Hood to imply cowardice was the reason for their reluctance.[8] Hood even refused to wait for Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee’s corps to catch up with the rest of the army, even though Lee still had the bulk of the Confederate artillery.[9] As a result, Hood’s infantry would be approaching the heavily fortified Union positions across two miles of open terrain without the support of massed artillery fire. Hood’s attack began at around 4PM.[10]

This is the view which would have appeared to Union defenders in 1864. The Confederates had to march across open terrain for nearly two miles before finally coming up to the Union line. Photo: Warfare History Network.

Hood’s army begins its assault at 4PM, approaching from the south. Photo: Wikipedia.

Almost as soon as the Confederates were within range, they came under heavy Union cannon and musket fire and began taking casualties. Despite the losses the Confederates were taking, the Union’s defenses were nearly undone by two Union brigades commanded by Brigadier General George Wagner, which had been positioned as an advance guard half a mile in front of the main Union line. Wagner’s men were quickly overwhelmed and began retreating straight into the defensive positions. Seeing blue-clad troops mixed in with the approaching mass of grey, many Union troops in the front lines held their fire. As a result, Confederate soldiers from Major General Benjamin Cheatham’s corps began penetrating the initial line of trenches. Several northern units turned and ran as positions were overwhelmed. East of the main road, a position which contained a battery of Kentucky artillery and supported by the 100th and 104th Ohio regiments was overrun and forced to retreat.[11] It was at this juncture that the third of Wagner’s brigades stepped in to plug the gap. Brigadier General Emerson Opdycke was a headstrong commander who had refused to obey orders to position his men on the opposite side of the road as Wagner’s other two brigades. After taking significant casualties during the rear guard action at Spring Hill, Opkycke had no patience for taking a position he saw as untenable, and moved his men to the rear of the fortifications to rest, eat, and have some coffee. Subsequently, Wagner told Opdycke he could fight in reserve as he saw fit.[12]

By this time, the Confederates, doggedly determined to push forward heedless of their losses, had captured a 200-yard section of the line stretching from the Carter farm’s cotton gin to a locust grove west of the road. Approximately 15-17 Union regiments had been driven back, many in a rout. At this critical moment, Opdycke, positioned 200 yards north of Carter House, drew his revolver and ordered his men forward to plug the gap with a cry of, “First Brigade, forward into the works!”[13] Opdycke’s earlier frustration proved fortunate- his brigade closed the gap and allowed the Union lines to stabilize- many soldiers who had retreated earlier now returned and began supporting Opdycke. Opdycke’s men and the stragglers pushed forward into the trenches from the Carter yard, shooting and bayoneting Confederates who stood in their way. Men from Cox’s and Wagner’s units rallied around Opdycke’s brigade and formed a group of troops four to five ranks deep and began firing muskets as rapidly as possible, passing them backwards to be reloaded by the men in the rear.[14] Against this wall of fire, the Confederates could not hold their ground- many began falling back to the main Union line, seeking cover.

Colonel Emerson Opdycke was a headstrong brigade commander who had been born in Ohio in 1830. He fought at Shiloh, Chickamauga, Chatanooga, and in the Atlanta campaign. Opdycke’s refusal to follow his division commander’s orders ultimately proved a godsend- his brigade formed a reserve which plunged into the gap punched in Union lines by the Confederate assault. Photo: Wikipedia.

Hood’s Army assaults the Union line from 5-9PM. Photo: Wikipedia.

Meanwhile, a salient had developed near the cotton gin in the Carter yard, around which many southerners were clustered. As the Confederates near the Carter house fell back, a stalemate began to develop in the lines. Southern forces tried to assault other portions of the Union line in an effort to push forward- the division of Major General Edward Walthall along with a brigade under Brigadier General William Quarles charged against the defensive positions of Colonel John Casement just to the east of the cotton gin. These positions had been fortified with a thick abates, and the shrubs to the front of the position had been cut down, giving the infantrymen an excellent field of fire. Making matters worse for the Confederates was the fact that some of the Union troops were armed with repeating rifles- soon, scores of killed or wounded Confederate soldiers were piled upon one another. Having taking horrid losses, the remnants of this southern attack moved west towards the cotton gin. There, Union troops from a division commanded by Brigadier General James Reilly were holding against an attack by Southern Brigadier General Charles Shelley.[15] At this position, a formidable Union artillery position consisting of two 12-pounder Napoleons of the 6th Ohio Light Battery under Lieutenant A.P. Baldwin were firing point blank into the charging Confederates.[16] A captain at that position described the scene:

“I went to a gun of the 6th Ohio Battery, posted a short distance east of the cotton gin… the mangled bodies of the dead rebels were piled up as high as the mouth of the embrasure, and the gunners said that repeatedly when the lanyard was pulled the embrasure was filled with men, crowding forward to get in, who were literally blown from the mouth of the cannon… [Lieutenant] Baldwin of this battery has stated that as he stood by one of his guns, watching the effect of its fire, he could hear the smashing of bones when the missiles tore their way through the dense ranks of the approaching rebels.”[17]

The Confederate soldiers were equally horrified by their losses; one Tennessee soldier wrote, “O, my God! What did we see! It was a grand holocaust of death. Death had held high carnival… The dead were piled the one on the other all over ground. I never was so horrified and appalled in my life.”[18] Despite the devastating losses, Hood was determined to press forward. He continued committing men in piecemeal attacks- these units were shredded by the Union defenses. One unit, the brigade of Brigadier General Francis Cockrell was obliterated on the western side of the Union line, sustaining 60% casualties to its 687-man strength.[19]

The Carter family cotton gin, around which a salient formed in the Union line and for which so many Confederates died attempting to take. The structure was so severely damaged that it had to be destroyed not long after the battle. The ground on which it stood was formerly occupied by a Pizza Hut, but today is preserved as a battlefield park. Photo: Warfare History Network.

Eventually, Union troops gained control of the cotton mill and used it to fire directly into the flanks of Confederate troops to the sides, incurring even more casualties. Refusing to admit defeat, Hood continued to commit more men. By this time, it was long dark, and the only visible signs of the battle were the flashes of cannon and musketfire. One of the many losses that night was Captain Tod Carter, a quartermaster with the brigade of Brigadier General Gist, and one of the sons of Fountain Branch Carter, the owner of the home that seemed the centerpoint of the battle. Carter had joined the 20th Tennessee infantry when the war began and had seen action at numerous battles including Missionary Ridge, and had even escaped captivity after being captured at Missionary Ridge. Now, as his brigade was shot to pieces, Carter rode forward on horseback trying to rally the men around him- only to be shot nine times, mortally wounded only 530 feet from the home he had grown up in. After the battle, Carter’s family found him on the battlefield and carried him inside, where he died on December 2nd.[20]

Major General Patrick Cleburne leads his men in the charge at Franklin. His horse was shot out from under him, and he would be last seen charging on foot, sword in hand. His body was later found just inside Union lines. Photo: Don Troiani.

Captain Fountain Branch Carter was mortally wounded just a few hundred yards from his childhood home- he would die there two days later. Photo: Battle of Franklin Trust.

Hood committed his last available reserve to attack at 9PM- the 2700 men under Mejor General Edward Johnson’s division. Advancing by torchlight, Johnson’s men got as far as the first line of Union trenches before they were met with tremendous cannon and musket fire. Over the course of an hour, Johnson’s division suffered 587 casualties before they withdrew. By 11PM, the shooting had stopped and the only sounds remaining were the groans of the wounded spread across the battlefield.[21] By midnight, Schofield ordered his men to begin withdrawing towards Nashville, 25 miles to the north. By 3 AM, the last of the Union defenders had withdrawn from the area.[22]

Confederate losses at Franklin were appalling. Hood had gotten around 27,000 of his men into the fight- he had taken over 5500 casualties, including 1,750 killed- a casualty rate of 20.6%, the 8th costliest battle of the war for the South.[23] Historian James McPherson wrote of the battle:

“Hood had lost more men killed at Franklin than Grant at Cold Harbor or McClellan in all of the Seven Days. A dozen Confederate generals fell at Franklin, six of them killed, including Cleburne and a fire-eating South Carolinian by the name of States Rights Gist. No fewer than fifty-four southern regimental commanders, half of the total, were casualties.”[24]

Hood had lost more men at Franklin than Lee had during Picket’s charge on July 3, 1863- there, Lee had lost over 1400 killed.[25] Major General Patrick Cleburne, mentioned in the above McPherson quote, had been a well-known leader who had risen through the ranks after enlisting as a Private at the beginning of the war. He had tried to lead his men from the front against Opdycke, but was fatally wounded after having two horses shot from under him- the following day, he was supposedly found with 49 bullet wounds.[26] Against these losses, the Union had gotten off relatively lightly- 2,326 casualties, including 189 killed.[27] Hood would blame his subordinates for the abject failure, writing extensively of the defeat in his postwar memoirs and insisting that despite his grievous losses in front of Franklin, his tactics had been sound and trenchworks were not the future of war:

“General Lee never made us of entrenchments, except for the purpose of holding a part of his line with small force, whilst he assailed the enemy with the main body of his Army… He well knew that the constant use of breastworks would teach his soldiers to look and depend upon such protection as an indispensable source of strength; would imperil that spirit of devil-me-care independence and self-reliance which was one of their secret sources of power, and would, finally, impair the morale of his Army… a soldier cannot fight for a period of one or two months constantly behind breastworks… and then be expected to engage in pitched battle and prove as intrepid and impetuous as his brother who has been taught to rely solely upon his own valor. The latter, when ordered to charge and drive the enemy, will- or endeavor to- run over any obstacle he may encounter in his front; the former, on account of his undue appreciation of breastworks…, will be constantly on the look-out for such defenses. His imagination will grow vivid under bullets and bombshells, and a brush-heap will so magnify itself in dimension as to induce him to believe that he is stopped b a wall ten feet high and a mile in length. The consequence of his troubled imagination is that, if too proud to run, he will lie down, incur almost equal disgrace, and prove himself nigh worthless in a pitched battle.”[28]

Whatever Hood’s excuses may have been, his career in the Confederate Army was not long for existence. Two weeks after the end of the Battle of Franklin, what remained of Hood’s army was destroyed at the Battle of Nashville. The survivors retreated back across the Tennessee state line, and Hood resigned from his post in January 1865, and did not hold another command for the rest of the war.

In the wake of the battle, the Carter family farm, the land on which the battle had been fought, never truly recovered. Hundreds of bodies were piled up in the yard and near the cotton gin, which had been riddled with countless bullets. The farm was eventually sold off by the family in 1896, passed through several hands before being bought by the state of Tennessee and is today preserved as a historical house. Today, visitors to Franklin may visit the Carter House along with several other remaining structures from the battle. The Battle of Franklin Trust (BOFT) is an organization which has dedicated itself to preserving as much of the battlefield as possible. In the years since the battle, urban development overtook much of the site. The BOFT has however had success in saving and preserving some tracts of land where the battle was fought. In 2006, an old Pizza Hut near the Carter House was raised and the property purchased- it now exists as a small park- immediately south across the street is a pile of cannonballs indicating the rough location where General Cleiburne is believed to have fallen. BOFT built a small museum and visitor center near the Carter House- visitors may purchase tickets which will allow them access to the Carter House, Lotz House, and Carnton Plantation. The Carter House has been well-preserved, with much of the original furniture remaining in the building along with some important artifacts, including the field desk of General Cox. The southern face of the house and its neighboring out-buildings remain pockmarked with bullet and shrapnel marks- the wooden office building is particularly sobering- here, holes in the southern wall align with holes on the northern side where bullets blasted their way completely through the building. Across the street to the east is the Lotz House; the author did not go inside the house during his visit, however, the house has been turned into a small museum. About two miles east is Carnton, a plantation on the eastern flank of the battlefield which was made an impromptu hospital. Approximately 20-30 acres surrounding the former plantation have been preserved as a battlefield park, with walking paths and placards placed throughout the field. Just to the northwest of the house is the Confederate cemetery- the McGavoks gave two acres of their property to be used as a burial site for nearly 1500 soldiers in 1866. I did not have time to visit Carnton before it closed for the day, but the house appears to have been well-preserved, and a second visitor center is located just outside. Guided tours are offered in various packages for all three locations, though it should be noted for those interested in traveling to the site that indoor photography is not allowed. The three sites are open seven days a week, with shorter hours during the weekend- prices vary based on the number of sites visitors wish to visit, from about $20 for a guided tour of Carter House up to nearly $50 for a bundled package for all three locations.

Despite the urban growth of Franklin in the intervening 150 years, the sites which have been preserved have conveyed some sense of the importance of the battle, and have particularly shown how the residents of Franklin weathered that battle. However, the changes in terrain around where the fighting occurred has also made it somewhat difficult to imagine the difficulties that the Confederates faced in taking the Union position, as well as making it hard to imagine the heaps of corpses which were piled around Carter House and the cotton gin. Only the scarred structures on the Carter property bear testimony to the ferocity of the battle and the desperation with which it was fought.

The Carter House. Built in 1830, this building has been converted into a house museum and furnished with as much period furniture as possible- much of it is original to the family. Among the most remarkable artifacts inside is General Schofield’s field desk. The southern face of the building is pockmarked with numerous bullet and shrapnel holes. The house is open for tours, though it should be noted that no photography is allowed inside. Photo: Author.

Impact marks on one of the outhouses on the Carter property. Photo: author.

The Carter family office building- this structure is the most telling of all the buildings in the property- several bullets clearly penetrated completely through one side and out the other- the inside of the building shines with numerous rays from the hundreds of holes in the walls. Photo: Author.

Immediately to the east of Carter House is the turnpike which the Confederates were advancing from the south on. This road still runs to Nashville, though it has of course been modernized several times over the years. Additionally, compared with the black and white photo early in this article, you can see how much the terrain has changed in 154 years- it has become much more developed and wooded, a far cry from the open fields of 1864. Photo: Author.

Three cannons stand along the area where the Union line once was. This is the property which was purchased by the Battle of Franklin Trust about 13 years ago following the demolition of the Pizza Hut which formerly stood on the site. About 150 meters in front of these cannons is a marker placed at the site where Cleburne’s body was found. Photo: Author.

A view from just south of the preserved park, looking north- this would have been just south of the main Union line. Photo: Author.

Just to the northeast of the battlefield is the remains of Fort Granger, a fortification built during the war. John Schofield set up his headquarters here and observed the battle’s progress. Guns here provided fire support to the Union line and hammered the Confederates as they approached Franklin from the south. The fort is open to the public and has several placards discussing the fort’s history. Photo: Author.

This viewpoint from Fort Granger is likely where Schofield watched his army defend Franklin. From here, he would have had a clear view of nearly the entire Union defensive positions and could make adjustments according to Confederate actions. Photo: Author.

Carnton Plantation, used as a field hospital by the Confederates, is also open to the public. Immediately after the war, the McGavoks, who owned the plantation, donated some of the property for use as a cemetery- nearly 1500 Confederate soldiers are buried here who were killed at Franklin. The land to the north of Carnton is also a battlefield park, with walking paths marked with placards crisscrossing the field in front of the house. Photo: Wikipedia.

Bibliography

1. Keegan, John. The American Civil War: a Military History. Vintage Books, 2010.

2. McPherson, James M. The Oxford History of the United States, Volume VI: Battle Cry of Freedom; the Civil War Era. Oxford University Press, 1988.

3. Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Univ. of Illinois Press, 2006.

4. Murray, Williamson, and Wayne Wei-sang Hsieh. A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton University Press, 2016.

5. McWhiney, Grady, and Perry D. Jamieson. Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage. University of Alabama Press, 1984.

6. “The Battle of Franklin.” The Battle of Franklin Trust. 2018. https://boft.org/history Accessed 12 June 2018

7. Walker, John. “The Battle of Franklin: John Bell Hood’s Catastrophic Defeat in Tennesseee.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 28 Apr. 2017, warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/. Accessed 12 June 2018.

8. “10 Facts: The Battle of Franklin.” American Battlefield Trust, History Channel, 13 Mar. 2018, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-battle-franklin . Accessed 12 June 2018.

9. Robinson, Carole. “Capt. Tod Carter's Tragic Death, a Life Lost Too Soon.” Williamson Herald, Blox Content Management System, 15 Nov. 2014. www.williamsonherald.com/features/special_sections/article_95d0431c-6d3c-11e4-9649-b7cb10965903.html . Accessed 16 August 2018.

10. “John Bell Hood Biography.” Civil War Home, CivilWarTalk Network, 1997, www.civilwarhome.com/hoodbio.html . Accessed 12 June 2018.

[1] P.276- The American Civil War: A Military History

[2] https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/john-b-hood

[3] P.812- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era

[4] P.812- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War era

[5] P.646- How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War

[6] P.453- A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War

[7] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[8] P.812- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era

[9] P.646- How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War

[11] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[12] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[13] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[14] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[15] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[16] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[17] P.456- A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War

[18] P.5- Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage

[19] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[20] http://www.williamsonherald.com/features/special_sections/article_95d0431c-6d3c-11e4-9649-b7cb10965903.html

[21] https://warefarehistorynetwork.com/daily/civil-war/the-battle-of-franklin-john-bell-hoods-catastrophic-defeat-in-tennessee/

[22] P.647- How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War

[23] P.11- Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage

[24] P.812-813- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era

[25] https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-battle-franklin

[26] P. 455- A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War

[27] P. 647- How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War

[28] P. 164- Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage