Capturing the Cradle of Nazism: The Battle of Nuremberg, April 1945

/A devastated nuremberg, looking towards the old city center across the Pegnitz at the end of the war. Photo: wikipedia.

By mid-April 1945, the end of the war in Europe was in sight. However, that did not stop ardent Nazis from holding out until the very end. In the southern state of Bavaria, the old German city of Nuremberg, already in ruins from repeated Allied bombings, became the scene of an intense urban battle as the American Seventh Army fought to take the city infamous for its pre-war Nazi Party Rallies.

By Seth Marshall

Mid-April 1945 saw the Allies advancing on all fronts into the heart of Germany. Despite the clear Allied advantages in men, equipment, and weapons, thousands of hardline Nazi officials continued to advocate resisting the Allied onslaught. This meant that even relatively small cities would become major points of resistance. Nuremberg, the second-largest city in Bavaria, would see one of the largest of these late-war urban battles. Unlike other cities which the Americans had fought for, Nuremberg had far more symbolic importance to both sides because of its role as the cradle of Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s.

Nuremberg has held an important role in Germany and its predecessors for centuries. The city dates back to at least 1040 when a castle was built at the city’s present location by King Henry III, duke of Bavaria, who would go on to become the Holy Roman emperor. During the 15th and 16th Centuries, the city flourished as a center for the arts, theology, and science during the Renaissance and Reformation periods; figures such as Albrecht Dürer, Michael Wohlgemuth, Veit Stoss, Adam Kraft, Philipp Melanchthon, Willibald Pirkheimer and Martin Behaim contributed to the city’s reputation. As it expanded, the city was granted status as a free imperial city. In 1806, during a period of decline, this status was revoked and the city became part of the Kingdom of Bavaria. The industrial era brought new life to the city as factories were built in and around Nuremberg.[1] In the 1920s, in the wake of the First World War, the city became a center for the Nazi Party. The Nazis held their first meeting in the city in early 1923, with the first rally coming later in the year. Several other rallies were held throughout the 1920s, before major rallies became an annual occurrence every September beginning in 1933. To support Nuremberg’s status as the “City of the Party”, architect Albert Speer was tasked with designing a massive expansion to the Rally Grounds. Much of the rallies took place at the Zeppelinfeld, a specially-designed parade ground taking up some 11 square kilometers.[2] The 1934 rally became possibly the most notorious- 152 anti-aircraft searchlights were positioned around the perimeter of the field and lit in a display which came to be known as the “Cathedral of Light.” Making this event even more notorious was Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will, which possibly included the most internationally-recognized images of the Nazi regime prior to the Second World War. During the following year’s rally, Adolf Hitler ordered the Reichstag to convene and decided on the Nuremberg Laws- a series of laws which effectively eliminated German citizenship of German Jews, banned marriage between Germans and Jews, and prohibited Jews from flying the German flag. Persecution of the Jews was not new in Germany, but the Nuremberg Laws made persecution of the Jews an official government policy.[3] Annual rallies would continue to be held through 1938- an additional rally was planned for 1939, but was cancelled when Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany the day before the rally was to begin. Additional construction was thereafter suspended on the rally grounds; construction workers and materials were needed elsewhere to support the war effort.[4]

During World War II, Nuremberg became an important industrial center. MAN had several factories in the Nuremberg area which produced diesel engine components for U-boats, and later in the war MAN also had an assembly plant which was one of the main locations responsible for Panther tank production. Other factories included Siemens-Schuckert, TEKADE, Nüral, and several other smaller firms responsible for producing various weapons, vehicles and equipment. The abundance of military industry, in addition to Nuremberg’s importance as a symbol of Nazism, meant that Nuremberg would be repeatedly bombed throughout the war. The first bombing raids occurred in 1940 and were carried out by the RAF’s Bomber Command. Early raids were relatively ineffective; night bombing was still a new technique and many bombers dropped their loads over completely separate areas. As the war went on and Allied air forces became stronger and more proficient, Nuremberg increasingly became the subject of raids. On the night of March 30-31st, RAF’s Bomber Command dispatched nearly 800 aircraft to attack the city. Weather and moon conditions conspired against the RAF in a significant fashion on this night- solid low cloud cover combined with a full moon meant that the bombers could be clearly seen against the clouds, allowing them to be visually acquired by the German night fighters. The raid on Nuremberg that night resulted in the heaviest losses of the entire war for the RAF- 95 bombers were shot down, and another 10 bombers were written off as complete losses on their return to the UK. 545 RAF bomber crewmen were killed on the raid.[5] It was also later determined that many of the bombers which were not shot down bombed the wrong city- two of the Pathfinder aircraft had mistakenly dropped flares on Schweinfurt, previously the target of two costly USAAF raids, and many RAF bombers subsequently bombed that city by mistake. In any case, the raid had caused relatively little damage to Nuremberg.[6] Far more destructive was the raid which took place on the night of January 2-3, 1945. Just over 514 Lancaster heavy bombers and a small number of Mosquito Pathfinder aircraft attacked the city-this time, the RAF savaged Nuremberg. 1,835 civilians were killed, over 100,000 were left homeless, and the heart of the old city was devastated, ruining many of the historic landmarks in the Altstadt.[7] Just 10 bombers were lost in the raid.[8] Bombing raids by both the RAF and USAAF would continue until just days before the ground battle for the city began. By this time, the city’s pre-war population of 420,000 had fallen drastically- by the end of the war in Europe, only 180,000 residents would remain.[9] Most of this difference is made up by Germans who fled the city for the countryside, but thousands died in bombing raids, especially during the final 14 months of the war.

A map of the destruction to nuremberg created by city planners in february 1945. photo: city of nuremberg.

B-17s release their bombload on nuremberg in february 1945. photo: USAAF Photo 53526, us library of congress.

By the spring of 1945, the situation in Germany had become dire. Allied armies were pressing in on all sides. In southern Germany, the US Seventh Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, was heading for Upper Bavaria. Organized German resistance was collapsing across Germany; as a result, defense of certain cities, mandated by Hitler, often fell to a cobbled-together mixture of forces including Wehrmacht, Waffen-SS, police, Volkssturm, conscripted civilians, and foreign volunteers. Nuremberg was to be no exception.

The leading Nazi official in Nuremberg was Karl Holz, the Gauleiter of Franconia. Holz was a veteran of the First World War, and had joined the Nazi Party in 1922. He was notably an editor of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, and rose steadily through the party ranks until 1940, when he was stripped of his titles in the wake of a corruption scandal centered around Julius Streicher, the main figure behind Der Stürmer. Recalled to military service, Holz fought in the invasion of France, and was badly wounded in June 1940. He returned to frontline service and participated in Operation Barbarossa before returning to Germany in late 1942 and resuming Party duties. He became the Gauleiter of Franconia in November 1944.

karl holz, the gauleiter of franconia at the end of world war ii. photo: bundesarchiv.

Six months after becoming Gauleiter, Holz’s future prospects looked grim. Germany’s strategic reserve had been sapped by the Battle of the Bulge, and further offensives in Alsace and Hungary had destroyed nearly all that remained of Germany’s once vaunted tank forces. Now, the US Seventh Army was driving southeast into Upper Bavaria. As the situation worsened, the Nazi regime became more desperate. On April 3rd, Head of the SS Heinrich Himmler issued an order that any male citizen showing a white flag outside of his residence was to be summarily executed. Civilians in and around Nuremberg were called up for service with the Volkssturm- the people’s militia- and given helmets, armbands and weapons. As American forces closed in, several civilians were executed by Nazi hardliners- among them was Werner Lorleberg of Erlangen, a town just north of Nuremberg, who attempted to open negotiations with advancing American forces, and teenaged student Robert Limpert, who was hanged in Ansbach for reportedly sabotaging German defenses.[10]

The defending German forces in Nuremberg were a hodgepodge of mixed units. Nuremberg fell within the 13th SS Corps sector, but in reality a large portion of the defenders were not SS. Elements of three battle groups formed the core of the defense; Kampfgruppe Dirnagel was mostly formed from SS soldiers, Kampfgruppe Rienow, staffed with Luftwaffe personnel, and the 1st Battalion of the 38th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment. These Kampfgruppe were collectively under the command of the staff of 9th Volksgrenadier Division, which had otherwise effectively ceased to exist.[11] In addition to this force was an unknown number of Volkssturm militia and Hitler Youth, and approximately 300 firemen and police officers being employed as infantry.[12] The most lethal defenses the city possessed included some 100 flak guns arranged in a rough ring around the city. Further afield, the Germans had committed the 2nd Mountain Division to defend territory northwest of the city, and the bulk of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadiers to the east of Nuremberg.

Elements of the US Seventh Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, continued to quickly advance even as the Germans strengthened the defenses around Nuremberg. The US XV Corps, commanded by General Haislip, turned towards Bamberg, north of Nuremberg. Bamberg quickly fell on April 13th, as the local German forces attempted to withdraw to prevent from being encircled. American forces then pushed on to take the city of Bayreuth the following day, before turning south. By this time, the Germans had relatively few tanks in the region. The largest concentration was a number of early model Panthers and now obsolete Panzer IVs at the Grafenwöhr training area. These tanks, together with over two companies of infantry were cobbled together to form a Kampfgruppe, with the objective of retaking Bayreuth. This came to nothing when the Kampfgruppe encountered the 94th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron of the 14th Armored Division at Creussen. Though the Germans surrounded the town, reinforcements from the 14th Armored Division coupled with intense artillery fire and air strikes by fighter bombers destroyed the Kampfgruppe, wiping out the only armored force capable of providing organized resistance against the oncoming American steamroller.[13]

Lieutenant General Wade Haislip, commander of US XV Corps, which was tasked with the capture of nuremberg. photo: wikipedia.

Having eliminated the German armored reserve, Haislip ordered his forces to turn south. It was anticipated that Holz and his military commanders had oriented their defense along the western edge of the city. To encourage this idea, the US XXI Corps held the 2nd Mountain Division to the northwest of Nuremberg, while the remnants of LXXXII Corps and most of 17th SS Panzer Grenadiers held the west. This left the eastern side of the city largely unprotected. Two divisions of the XVI Corps were tagged with taking the city- the 3rd Infantry Division and 45th Infantry Division. Both of these divisions had seen extensive combat during the war in Europe- both divisions had landed at Sicily, fought through Italy (including at Anzio), landed in Southern France, fought through the Vosges Mountains and finally had advanced across Germany. Both divisions had taken very heavy losses in the preceding two years of combat, but were well experienced, and unlike their German counterparts were relatively well-supplied, had better equipment, and could call upon far more support such as artillery, armor and aircraft. The 3rd Infantry Division would approach Nuremberg from the north, while the 45th would approach from the east and southeast. The XVI Corps’ reconnaissance element, the 106th Cavalry Group, quickly moved around to the south end of the city to cut off German elements attempted to retreat from the city while also providing early warning against any German reinforcements arriving from the south.[14] In completing this envelopment, XV Corps took nearly 4300 prisoners on April 15th alone. Aiding XV Corps advance was the P-47s of the XII Tactical Air Force, which flew 120 sorites bombing and strafing German elements in the region.[15] With Nuremberg now isolated by the XV and XXI Corps, the advance into Nuremberg itself could now begin.

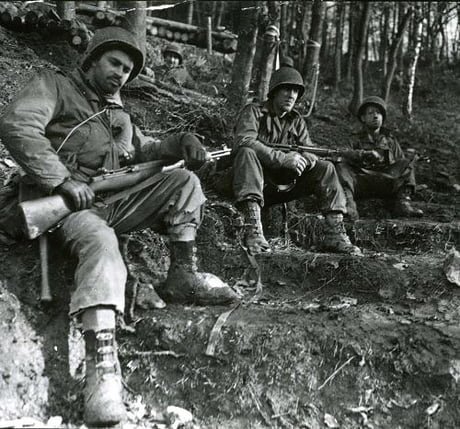

On the morning of April 16th, the Americans began pressing in towards Nuremberg. The 45th Infantry Division’s 179th Infantry Regiment began their attack by advancing through woods to reach several towns on the outskirts of Nuremberg, including Ruckersdorf and Rothenbach. At noon, the Regiment’s commander and executive officer were both wounded by mortar fire; in spite of this, the Regiment pressed on.[16] The Regiment began to receive increasing amounts of fire from the 88mm anti-tank guns which ringed the city, capturing several after overrunning their positions.[17] Despite Allied airpower’s overwhelming air superiority by this stage in the war, the Luftwaffe made appearances over the shattered city in the form of Me-262s, which attacked the 179th’s positions. The 179th would continue its attack through the night. To the north, the 3rd Infantry Division’s regiments began their advance before dawn, clearing the towns on that edge of the city, reaching Erlangen by mid-afternoon. After nightfall, the division began encountering increasing resistance and halted for the night. Inside the city, the Nazis had rigged explosives on the city’s gas, water and electricity stations- Arthur Schoeddert, a local radio announcer known on air as “Uncle Valerian” and who had been placed in charge of a number of anti-aircraft guns and was responsible for detonating the explosives, refused the order.[18] During the night, US infantry advanced through the marshalling yard after overcoming local flak batteries being used in a direct fire role.[19]

The next day at dawn, GIs moved out again to press in on Nuremberg. For Company E, 180th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division, the day was to be an eventful one. After rendezvousing with a platoon of tanks, the company advanced towards a German POW camp supported by the tanks and several weapons platoons from the battalion’s headquarters company. After some sporadic firing by machine guns posted in the German guard towers, which were promptly suppressed by the infantry, the tanks knocked down the perimeter fence and secured the camp within half an hour, at the end of which the camp commandant surrendered the camp. The GIs had liberated a camp which held some 13,000 prisoners, including 250 US and 450 British POWs. Next, the company was tasked with taking the imposing stadium which sat on the rally grounds, also known as the Kongresshalle. Advancing from the south, the company had moved into the woods immediately to the south of the stadium by mid-morning before beginning to take contact from German infantry. As the company continued to press through the woods, the company’s commander, Captain Paul Peterson was observing a new lieutenant struggling to lead his men forward.

“The new officer was leading his platoon in assault fire across a 50 yard fire break straight up on enemy prepared positions. The fire distribution and marching fire was perfect and every man advanced quickly towards the stubborn Germans… However, on reaching the first positions the Lieutenant lost control of his platoon. The officer suddenly had stopped and stood looking at a very much dead enemy soldier. The Lieutenant kept repeating, “I killed him, I killed him.””

After Peterson impressed upon the lieutenant the need to continue leading his platoon, the woods were cleared; 15 Germans were taken prisoner and 6 had been killed.[20]

By midafternoon, Company E had begun attacking the stadium itself, receiving a mixture of rifle, machine gun, and 88mm fire from the imposing structure. The Americans returned fire with light mortars and artillery called in from batteries supporting the battalion. Recognizing that a frontal attack on the Kongresshalle would result in heavy casualties, Peterson elected to move his men around the side of the stadium near the lake adjacent to the stadium. After artillery and fighter bombers softened up the German strongpoints in the structure, the company’s riflemen began advancing across the open pavement behind supporting tanks late in the afternoon. The GIs reached the stadium after suffering 3 wounded and 1 killed; Staff Sergeant Miles Hartzel, a well-liked platoon sergeant, was killed when a Panzerfaust detonated nearly at his feet. After reaching the hall, the GIs began the tedious task of clearing the structure.

“The building was finally reached and the squads started clearing each room. The enemy was holding out under the supervision of two or three fanatical SS troopers so placed to ensure that each person remained to defend the position to the last. Congress Hall was found not only to be four stories high and very wide but eight to ten rooms deep. By darkness, the building was only one-third cleared of enemy. Over one hundred prisoners were taken and at least 35 had been killed.”[21]

Company E had suffered another four wounded before nightfall; darkness brought an end to the fighting. The remainder of the Kongresshalle would not be taken until the following day. After darkness had fallen, the Germans probed Company E’s perimeter near some trolley tracks. A BAR gunner in the company’s 3rd Platoon, Corporal Manes, saw the approaching Germans and waited until they were just 25 yards from his position before opening fire, killing two and forcing the remainder to withdraw. April 17th had cost Company E at least 1 killed and 7 wounded.[22]

GIs of the 3rd Infantry Division work their way up a ruined street accompanied by a tank. Photo: National World War II museum.

A squad of GIs advance up a street behind a sherman tank. photo: the national World war ii Museum.

As American soldiers advanced into the city, the fighting devolved into intense house-to-house fighting. German soldiers would frequently fire Panzerfaust anti-tank weapons from upper windows at US armored vehicles, and 88mm guns would fire point blank at both vehicles and groups of infantry. US GIs were forced to clear buildings room by room to prevent stragglers from getting behind American lines and sniping at their rears. Further complicating matters for the Americans was that among the German soldiers were hardline Nazi civilians, who also took to firing Panzerfausts and throwing grenades at the Americans. By the end of the 17th, American forces had taken much of the Party Rally Grounds, the airfield north of the city, and had advanced up to the fire station in Veilhofstrasse in Woehrd. The old city center, already devastated earlier in the year by an air raid, now began to come under artillery fire.[23]

April 17th also saw the first Medal of Honor action during the Battle of Nuremberg. 1st Lieutenant Francis Burke of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division was his battalion’s transportation officer, but he went forward with the infantry to locate a new site for his unit’s motor pool. He encountered a squad of 10 German soldiers preparing to attack; he moved to an infantry unit and retrieved a machine gun with ammunition, then returned to where the Germans were and opened fire on the enemy squad. The Germans immediately returned fire. During the next four hours, Burke repeatedly ran through enemy machine gun, rifle and sniper fire to attack small elements of Germans and leading other groups of American soldiers in attacks on German positions. He single-handedly killed 11 German soldiers and wounded three others.

Lt Francis Burke recieves the medal of honor from president truman. photo: wikipedia.

The following day, April 18th, the fighting continued to press in towards Nuremberg’s old center. As the Americans continued to fight their way into the devastated city, Karl Holz withdrew into a bunker in the old city center with the city’s mayor, Willy Liebel- he would never leave. For the American GIs, the battle was turning into one of the most difficult urban fights of the war. Most of the buildings in the city, particularly near the center, had been reduced to heaps of rubble which spilled into the street and made movement by vehicles difficult. For most infantrymen and their supporting tankers, visibility was frequently limited to just 100 meters. Oftentimes the piles of rubble and few streets relatively clear of enough rubble for tanks to move along had the effect of isolating units until they were reduced to single companies, platoons or squads operating seemingly alone against a city that from their perspective was full of fanatical Nazis.[24] Artillery and tanks were frequently used to obliterate German strongpoints in buildings, but the abundance of destroyed buildings created many ideal hiding positions for German ambush teams and snipers. Snipers concealed in such positions later delayed US forces repeatedly during attempted crossings of the Main and Pegnitz Rivers.[25] The massive piles of wreckage in the city also created ideal blind spots for German anti-tank guns, including the dreaded 88mm. These guns would wait until a group of American GIs or tanks had rounded a corner before firing at point-blank range. Throughout the city, German resistance was characterized as tenacious; American infantry were forced to go house-by-house and clear every room to prevent stragglers from firing at the backs of passing Americans. The weather also created some difficulties for the US; while the generally warmer temperatures of April were likely welcomed by the same troops who had shivered during the brutal winter months of 1944-1945, the skies were frequently hazy or foggy, and occasionally rainy, which further reduced visibility and made it more difficult for Allied fighter bombers to accurately separate friend from foe during close air support missions.[26]

GIs advance behind heavily-laden sherman tanks on april 18th. photo: the national world war ii museum.

among the many factories around nuremberg which was overrun by us forces was the man factory, responsible for assembling panther tanks. at the time of the factory’s capture, several panthers were outside the plant on flatcars, awaiting repairs for battle damage. photo: ww2.live.com

For Company E of the 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, fighting on the 18th began before the dawn broke. At 0500, the company reentered the Kongresshalle and continued clearing rooms using white phosphorous and fragmentation grenades. The remaining Germans capitulated relatively quickly; by 0630, the massive structure was secure. Another 75 POWs were taken, and 300 civilians were removed.[27] The company received new orders to move out just 15 minutes later. Some of the company’s attached tanks were replaced with tank destroyers, providing a mix of armored vehicles for support. Just before stepping off into the attack, Company E received a substantial amount of German mortar fire just prior to a counterattack by about a platoon’s worth of men, which was quickly routed. Moving out at just past 7 in the morning, the company encountered growing resistance just a couple of hours later. Captain Peterson wrote:

“This section of the city had been formerly a very pretty residential part of Nuremberg. Now it was a jagged mass of ruins with only an occasional house that hadn’t been entirely gutted. The defender used this rubble to the fullest extent possible. The enemy further started at this time, to use children and old men to do the observing. The man or child would be noticed walking up to a corner near front line positions, stand for a while and then slowly amble away. Shortly thereafter artillery and mortar fire would pinpoint the company positions. Orders were given to the platoon leaders by the Company Commander to fire on any future “observers” of this type.”[28]

At one point, the company came under fire from an 88mm gun supported by about a platoon of infantry. While two platoons placed the position under covering fire from the front, Lieutenant Fee led his 1st Platoon around the German position’s right flank, cleared the buildings there, and then assaulted the gun position, killing 20-25 of the Germans and taking just 3-4 prisoners. The company paused for several hours to rest, then resumed the attack at 2PM. After clearing two apartment buildings, Lieutenant Fee, who had led his platoon in the assault on the German gun that morning, was killed by machine-gun fire just as he had been about to through a white phosphorous grenade to attack a road-block. As the day’s light faded, the company continued the attack. Both the 1st and 3rd platoons encountered heavy resistance from Germans firing Panzerfausts and 20mm cannons and launching counterattacks. By the time the company ceased its advance for the day, it had killed 35 Germans and taken another 130 prisoner. Company E lost five killed and seven wounded that day.[29]

April 18th also saw two Medal of Honor actions. Lieutenant Michael J. Daly of the 3rd Infantry Division was leading his platoon through the wreckage of the city when they began receiving machine gun fire. Advancing alone, Daly killed the three-man machine-gun crew with his carbine. Continuing forward at the front of his platoon, Daly encountered a German patrol armed with Panzerfausts. For a second time, Daly moved ahead of his platoon, gained a position on the Germans, and killed all six of the Germans. Next, the Lieutenant led his platoon into a park. Coming under machine-gun fire again, Daly killed the gunner of one machine-gun with his carbine, then directed one of his machine-gun crews to fire on the remaining German gun crew members until they were dead. Finally, Daly engaged a third machine-gun at the very short range of 10 yards, again wiping out the crew. During four separate engagements, Daly had placed himself at significant risk and killed 15 Germans. The next day, Daly was shot in the face and sent to the rear to recover.[30][31] Near Lohe, in Nuremberg’s northern suburbs, Private Joseph F. Merrell, just 18 years old, advanced with the rest of Company I, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division towards some hills controlling the terrain north of the city. His company came under heavy fire from two heavy machine guns supported by infantry armed with rifles and submachine guns. Completely disregarding his own safety, Merrell sprinted 100 yards through heavy German fire, and came upon four Germans firing submachine guns. Exchanging fire with them, bullets ripped his uniform but apparently left him as yet unharmed, while all four Germans were killed. At this point, Merrell’s rifle was hit and destroyed by a sniper bullet, leaving him armed with only three grenades. Undeterred, Merrell dashed from cover to cover for another 200 yards to within 10 yards of the first machine gun position. He threw two grenades, then charged the position unarmed. Once in the machine-gun post, the commandeered a Luger pistol and killed the remaining German machine gunners. Crawling another 30 yards to the next machine-gun, he killed another four Germans in foxholes but was shot in the abdomen in the process, badly wounding him. Still determined to press on, he staggered on to the second machine-gun, all the while still being shot at by German infantry. He threw his last grenade into the second machine-gun post and killed the remaining crew with his pistol, before finally being cut down by a burst of submachine gun fire. In his one-man charge, Merrell had eliminated both machine-gun positions and killed over 20 German soldiers. His body was returned to the US and buried in his home state of New York.[32]

Lt Michael J. Daly recieves the medal of honor from president truman. photo: wikipedia.

Private joseph Merrell, who was posthumously awarded the medal of honor for his actions on April 18, 1945. photo: congressional medal of honor society.

By April 19th, the 3rd and 45th Infantry Divisions were set on clearing up to the old city center- the heart of Nuremberg and the former seat of the Holy Roman Emperor. The old city presented a formidable obstacle for the Americans; a massive stone wall ringed the old city and was reinforced with tall towers. These fortifications had stood for hundreds of years and had even withstood the multiple bombings during the previous years.

Among the American units which had not yet advanced up to the old city walls was 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Felix Sparks. A relatively young battalion commander at 28 years old, Sparks had risen through the ranks after his commission as a Second Lieutenant in January 1940. He had been in action for nearly two years by the time of the Battle of Nuremberg. On the morning of April 19th, Sparks had ordered two of his companies to continue pushing towards the old city; Sparks followed the infantry in his jeep to stay in close contact with their commanders. Alex Kershaw, author of The Liberator wrote about what happened next:

“Sparks had deployed two companies and now followed close behind in a jeep, drive as usual by Turk, and with his runner Johnson and interpreter Karl Mann in the backseat. Yet again, he wanted to be as close as possible to the front lines. But it was difficult to find a path through the endless acres of rubble. Turk drove slowly as Sparks tried to spot street signs amid the blocks that had all but disappeared. Then he saw the Opera House with its enormous green roof. Sparks turned to his driver. “Uh oh. I think we’ve gone too far.” Turk pulled up. Sparks realized that he had not only caught up with his companies but had in fact overshot them. Once more, he looked at his map, which he usually spread out on the hood of the jeep in front of him. Then, from the high dome of the Opera House, a German machine gunner fired a burst at Sparks and his group. The rounds passed between Sparks and his driver and between the legs of the men in the backseat. They abandoned the jeep, which also carried the command radio and the radio code. Incredibly, no one had been hit. The burst had gone under Sparks’s arm before putting a big hole in the jeep. Sparks and the other men ran for cover in the nearest shell-holed buildings. Then they made their way back until they met up with Sparks’s lead rifle company.”[33]

Sparks’s experience was not a unique one among the American units pushing ever deeper into Nuremberg. Another battalion in the 157th Infantry Regiment would cross the Ludwig Canal under sniper fire and seize bridges for additional forces to cross. In 3rd Infantry Division’s sector, the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment captured a company of the Nuremberg’s police force at Westfriedhof Cemetery, who had been impressed into service as infantry. Before the end of the day, the battalion had crossed the Pegnitz River had advanced up to old Nuremberg’s walls.[34] The 7th Infantry Regiment also moved up to the walls by evening, receiving a counterattack by a group of suicidal Luftwaffe trainees attacking from the ruins of Nuremberg Castle- the attack was quickly destroyed.[35] The 30th Infantry Regiment encountered fierce resistance which nearly overwhelmed one of the unit’s companies before a counterattack caused the Germans to withdraw. Later in the afternoon, Second Lieutenant Telesphor Tremblay surrounded one of the fortification’s watchtowers, the Laufer Tor, with his anti-tank platoon. 125 Germans were holed up in the tower, and Tremblay and his men fired at Germans repeatedly with their personal weapons before bazookas were brought up and fired en masse at the tower. This prompted the surrender of the Germans inside the tower.[36]

As the leading elements of the 30th Infantry Regiment advanced up to St. Johannis gate, some GIs were sent forward to send a message to the Germans over a loudspeaker.

“Your city is completely surrendered and the old city has been entered in several places. People in the occupied part of the city are being treated humanely. Your unconditional surrender will be accepted under the following conditions: Raise white flags over the buildings and open all entrances to the inner city. Otherwise you will be destroyed. We will not wait, so act quickly.”[37]

There was no response from the apparently quiet walls and wrecked buildings. The Germans had blocked up the gate, so a M12 155mm self-propelled gun was brought forward to fire directly at the walls and gates. The gun fired twenty rounds, forming large craters in the walls and throwing stone chips everywhere, but not causing any severe damage. Nonetheless, the Germans at St. Johannis gate surrendered; a path was now open into the old city itself.[38]

A Sherman with the 45th infantry division advances up a rubble-strewn street in the heart of nuremberg while infantry crouch behind the ruins of buildings. photo: NARA.

A GI peers down a street under fire from german postions behind the cover of a sherman tank. photo: nara.

Two shermans stopped outside of the old city- judging by the relaxed attitudes of the tanks, fighting has already ceased in the city. photo: nara.

April 20th was to be the final day of the battle for the city. It also happened to be Hitler’s birthday. With the defender’s ammunition beginning to run low and his situation hopeless, Karl Holz sent a final message to Hitler.

“My fuehrer, the final struggle for the town of the party has begun. The soldiers are fighting bravely, and the population is proud and strong. I shall remain in this most German of all towns to fight and die. In these hours my heart beats more than ever in love and faith for the wonderful German Reich and its people. The National Socialist idea shall win and conquer all diabolic schemes. Greetings from the National Socialists of the Gau Franconia who are faithful to Germany.”[39]

Hitler sent a response to Holz:

“… I wish to thank you for your exemplary conduct. You are thereby bolstering the spirit not only of people in your own Gau, to whom you are a familiar figure, but also millions of Germans. Now starts the fervent struggle which recalls our original struggle for power. However great the enemy’s superiority may be at the present moment, it will still crumble in the end- just as it had done before. I wish to show my appreciation and my sincere gratitude for your heroic actions by awarding you the Golden Cross of the German Order.”[40]

Even this late in the war with the clear Allied superiority in men, equipment and vehicles and their inexorable advance across Germany, Hitler and his subordinates still held a delusional belief in the final victory of Nazism over Germany’s enemies. This was demonstrated all too clearly for the Americans at Nuremberg; April 20th would be the culmination of the fight for city notorious for its role within the Nazi Party.

The fighting on the 20th began early, with a large German counterattack mounted at 4AM to try and breakthrough the American encirclement. This attack took some American companies by surprise and nearly overwhelmed them before the German attack petered out and the survivors either surrendered or withdrew. Behind them, the Americans began moving up to wipe out the last remaining pockets of resistance. Company E, 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division had spent the 19th in reserve. On the morning of the 20th, Company E was reinforced with a platoon from Company F and a platoon of tanks, then sent through the medieval wall after by squads under cover of white smoke. The company encountered only sporadic resistance, which prompted Captain Peterson to send his tanks forward to suppress the Germans.[41]

The company took large groups of prisoners as it advanced along the narrow, rubble-strewn streets. By noon, the company had taken 250 prisoners. The company was still encountering resistance, usually a group of Germans led by an SS soldier who refused to let his fellow countrymen surrender and fought to the very end. On one occasion, a German position waited until the tanks came into view, then fired flanking machine-gun and anti-tank fire at one of the attached Shermans. Unable to fire initially at the Germans because of a wall, the tank poked its barrel through a window, blew out the wall of a building with one shot, then proceeded to fire another 15 rounds into the German position, silencing it permanently. By now, the Germans were surrendering in groups of 25-50 at a time. By the end of the day, the company had taken 750 prisoners and killed 45-50 Germans, losing just three wounded in the process. During the four-day battle for the city, Company E had lost 6 killed and 17 wounded.

Elsewhere in the old city, other US units were doing much the same, clearing buildings room by room, and pulling surrendering Germans from their hiding spots in basements and air raid shelters. It is not known with certainty how Gauleiter Karl Holz died. He had been holed up in Palmenhofbunker at the Nuremberg Police Presidium since the 18th; when he likely killed Liebel. Holz remained in the basement as American soldiers began firing on the building above. Holz either committed suicide or was killed in the fighting. Holz’s second-in-command, Colonel Wolf, realized the situation was completely hopeless and ordered the remaining Germans to lay down their arms- he issued this order at 11AM.[42] In the very heart of Nuremberg, elements of the 3rd Infantry Division would overwhelm the last of the defenders at Adolf Hitler Platz, were two hundred Germans continued to hold out the very end. These Germans were finally killed when GIs lowered explosives into their tunnel and set them off.[43]

american tanks advance into the old city of nuremberg, likely on the final day of fighting. photo: nara.

Gis in the streets near st. sebalduskirche, one of the oldest churches in the city. fighting appears to have ceased, as the gis appear relatively at ease. photo: nara.

US infantry march down the street from nuremberg castle towards the main square in the old city. photo: Nara.

GIs of the 3rd infantry division move through the recently-secured city of nuremberg towards the frauenkirche and city square on april 20th. photo: nara.

At the end of the fighting, the tired men of the 3rd Infantry Division assembled in Adolf Hitler Platz for a division review in front of Major General John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel. Following a speech by O’Daniel in which he congratulated his division on its role in taking the city, the Division band played the Division’s song, “Dog-Faced Soldier.” [44]Two days later, both the 3rd and the 45th Infantry Divisions assembled for an inspection in front of Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, commander of XV Corps. Even though the fighting for the city had ended two days before, Nazi sympathizers remained present; one of Lieutenant Colonel Sparks’ soldiers was killed by a sniper later on April 22nd after the parade had ended.[45]

The Battle for Nuremberg had been one of the more intense urban battles fought by American forces in Western Europe, and one of its costliest late-war battles. The 3rd Infantry Division and its attachments suffered 147 killed, 601 wounded and 7 missing. Casualties for the 45th Infantry Division are less certain- the 157th Infantry Regiment lost 4 killed, 44 wounded during the battle, but the 180th Infantry Regiment had lest specific records, noting that during the entire month of April the Regiment had lost 75 killed, 312 wounded, 5 missing and 7 died of wounds.[46][47] Similarly, the 179th Infantry Regiment recorded that between April 1st and April 30th, the Regiment lost 35 killed, 175 wounded and 1 missing.[48] Additional units in the 45th suffered smaller numbers of casualties, such as the 120th Combat Engineer Battalion with 1 killed, 14 wounded.[49] It seems reasonable to assume that the 45th suffered a similar level of casualties during the Battle for Nuremberg as the 3rd Infantry Division; the overall casualty figures for the US likely range between 290 killed, 1200 wounded and 15 missing.

A knocked-out sherman on the edge of the zeppelinfeld following the capture of the parade grounds. photo: nara.

GIs frequently took the opportunity to mockingly make the nazi salute on the very same podium from which hitler gave speeches at party rallies. photo: nara.

Members of the 3rd infantry division parade through the main square in nuremberg in front of the frauenkirche on April 22nd. photo: nara.

A gi looks across the pegnitz to the shattered remains of nuremberg’s old city; the bombed-out frauenkirche can be seen in the background. photo: nara.

Today, Nuremberg has changed significantly from its state during the ground battle. The city had been completely destroyed between the bombing and ground battle in April; in the years which followed the war, the city was rebuilt. Today, many of the buildings which stood in 1939 before the bombing campaign are gone, replaced frequently by more drab and slab-sided modern structures which contrast with those classical buildings which were restored to their former glory. However, some of the pre-war buildings have survived, including a small number which were scenes of the fighting in 1945. The Deutscher Hof Hotel, which Hitler stayed at during his visit to the city in 1934, remains standing albeit with a post-war facelift. The Fränkischer Hof, where the Nazi press stayed during Rallies, also remains standing, although it was modified significantly in the decades since the war and is now a Sheralton Hotel. The Hauptbahnhof (main train station) also remains standing, though it needed significant repairs after war. One of the most visible remnants of the pre-war era is the Hauptmarkt, the main city square. This square lies in the old city, and was the location of the final remnant of German resistance as well as 3rd Infantry Division’s first parade. This square today remains the scene of markets on weekends, various public events, and the massive Kriskindlsmarkt during the Christmas holiday season. St. Sebalduskirche, located on the eastern end of the square, also remains standing, though it too required extensive renovations in the post-war era after having its roof blown in by a bomb. The Gauhaus, built in 1937 for the Gauleiter of the region, was burnt out during the battle, but has also been rebuilt and sits on what is now called Willy-Brandt-Platz. Unlike many of the city’s other churches damaged during the war, St. Katherine’s Church was not rebuilt- the shell remains standing in the old city. Perhaps the most striking remnants of the Nazi era still left in Nuremberg are the Party Rally grounds- most of the components of these grounds remain standing, including the podium where Hitler spoke at the Zeppelinfeld, and the incomplete Kongresshalle, which has been converted into a museum on the history of the Nazi Party in Nuremberg and the effects of the policies and rallies held in the city.[50]

The Battle of Nuremberg was one of the last major battles fought by the Western Allies in the European Theater, and its ferocity and desperation characterized the fighting taking place in Germany at this stage of the war. It was also a symbolic battle, with many hardline Nazis fighting tooth and nail for the city so closely associated with the origins of the party and with its heinous policies. For the Americans, victory at Nuremberg came to signify their impending triumph over an evil regime which had murdered millions. A stark example of this coming end of Nazi Germany came about a few days after the battle. Atop the main structure at the Zeppelinfeld was a massive wreathed swastika. Deciding that the decoration no longer suited the city, the Americans carried a couple hundred pounds of high explosives atop the structure and blew the swastika into fragments, an event captured for all to see on newsreels, and which came to be a major symbol of the end of Nazi Germany.[51]

The Kongresshalle as it appears today, which company e, 180th infantry fought so hard to secure during april 16-17th, 1945. today, the interior is home to an excellent museum documenting nuremberg’s role during the nazi era. photo: author

the 2km-long marching road remains in place today, and is frequented by german pedestrians. photo: author.

THe main structure at the zeppelinfeld. the adjoining columns were demolished in the 1960s as a safety hazard. today, a racetrack runs through the former parade ground, though all of the concrete viewing stands remain in place, and it is still possible to see how large the parade field was. photo: author.

The lorenzkirche as it appears today. photo: author.

the waterfront along the pegnitz, which had been completely demolished during the bombing, has been completely rebuilt since. photo: author.

The frauenkirche was rebuilt after the war- today, it remains the centerpiece of the main city square, which is still used for markets. photo: author.

St. Sebalduskirche, also badly damaged by bombing in 1945, has been rebuilt along with most of the other historical churches in nuremberg’s city center. photo: author.

nuremberg castle had suffered extremely heavy damage during both the bombings of 1945 and during the fighting; it has since been effectively rebuilt, and much of the interior has been converted for museum space on the history of the holy roman empire in the city. photo: author.

Sources

1. Beall, Jonathan Andrew. “‘The Street Was One Place We Could Not Go’: The American Army and Urban Combat in World War II Europe.”

2. Bradsher, Greg. “The Nuremberg Laws: Archives Receives Original Nazi Documents That ‘Legalized’ Persecution of Jews.” Prologue, vol. 42, no. 4, 2010, https://doi.org/https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2010/winter/nuremberg.html.

3. Dierl, Florian, et al. “The Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg - Google Arts & Culture.” Google, Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds, Nuremberg Municipal Museums, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-nazi-party-rally-grounds-in-nuremberg-documentation-center-nazi-party-rally-grounds/9gXBnoIq2KGTIg?hl=en.

4. Eisenack, Gabi. “Nürnberger Remembers the Bombing Raid of January 2, 1945.” Nordbayern, Nordbayern.de, 2 Jan. 2013, https://www.nordbayern.de/region/nuernberg/nurnberger-erinnert-sich-an-bombenangriff-vom-2-januar-1945-1.2603905.

5. Fell, David William. “Operation – Nuremberg - 30/31 March 44.” 576 Squadron- RAF, 13 Base- RAF, https://www.northlincsweb.net/576Sqn/html/nuremberg_30-31_march_1944.html.

6. Goldstein, Richard. “Michael Daly, 83, Dies; Won Medal of Honor.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 July 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/us/29daly.html.

7. Headquarters, 45th Infantry Division, APO, AE, 1945, Historical Record of the 157th Infantry for the Month of April 1945.

8. Headquarters, 45th Infantry Division, APO, AE, 1945, Historical Record of the 179th Infantry for the Month of April 1945.

9. Headquarters, 45th Infantry Division, APO, AE, 1945, Historical Record of the 180th Infantry for the Month of April 1945.

10. Headquarters, 45th Infantry Division, APO, AE, 1945, Report of Operations of the 180th Infantry Regiment from 1 April 1945 to 30 April 1945

11. Hopkins, Ryan Patrick. “The Historiography of the Allied Bombing Campaign of Germany.” Thesis / Dissertation ETD, East Tennessee State University, 2008.

12. Kershaw, Alex. Liberator: One World War II Soldier's 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau. Broadway Books, 2012.

13. Lankford, James R. “Battling Segregation and the Nazis: The Origins and Combat History of CCR Rifle Company, 14th Armored Division.” Army History, ser. 63, 2007, pp. 26–40. 63.

14. MacDonald, Charles B. The Last Offensive. Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1993.

15. “Michael Joseph Daly: World War II: U.S. Army: Medal of Honor Recipient.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/michael-j-daly.

16. Munsell, Warren P. The Story of a Regiment: A History of the 179th Regimental Combat Team. Newsfoto Publishing, 1946.

17. “Nürnberg.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 Apr. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Nurnberg.

18. Peterson, Paul L. The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, April 15-20 (Personal Experience of a Company Commander). The Infantry Schhool, 1949.

19. Ranter, Harro. “Mid-Air Collision Accident Avro Lancaster Mk III PB515, 02 Jan 1945.” Aviation Safety Network, Flight Safety Foundation, https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/159046.

20. Rawson, Andrew. In Pursuit of Hitler: A Battlefield Guide to the Seventh (US) Army Drive (Battleground Europe). Pen & Sword Military, 2008.

21. Schaitberger, Linda L. “The End of a Benign and Ancient City: Six Centuries Lost in an Hour.” The 'near Perfect Area Bombing' of Nuremberg by the Royal Air Force, http://www.revisionist.net/nuremberg-bombing.html.

22. CSI Battlebook 13-D: The Battle of Nuremberg. Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, KS: 1984.

23. “The End of the War in Nuremberg.” Nuernberg Online, City of Nuremberg, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20070520114434/http://www.kriegsende.nuernberg.de/english/chronology/index.html .

24. Walden, Geoff. “Nürnberg.” Third Reich in Ruins, 20 July 2000, http://www.thirdreichruins.com/nuernberg.htm.

25. Zita Ballinger Fletcher (4/13/2023) Breaking the City of Kings: The Battle for Nuremberg, 1945. HistoryNet Retrieved from https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city-of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945/

[1] https://www.britannica.com/place/Nurnberg 12APR23

[2][2] https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-nazi-party-rally-grounds-in-nuremberg-documentation-center-nazi-party-rally-grounds/9gXBnoIq2KGTIg?hl=en

[3] https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2010/winter/nuremberg.html

[4] https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-nazi-party-rally-grounds-in-nuremberg-documentation-center-nazi-party-rally-grounds/9gXBnoIq2KGTIg?hl=en

[5] http://www.revisionist.net/nuremberg-bombing.html

[6] https://www.northlincsweb.net/576Sqn/html/nuremberg_30-31_march_1944.html

[7] https://www.nordbayern.de/region/nuernberg/nurnberger-erinnert-sich-an-bombenangriff-vom-2-januar-1945-1.2603905

[8] https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/159046

[9] P. 42- “The Historiography of the Allied Bombing Campaign of Germany” Hopkins, 2008

[10] https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city-of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945.htm

[11] The Last Offensive, p.423

[12] https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city-of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945.htm

[13] P.32- Army History: The Professional, 2007

[14] P.423- The Last Offensive

[15]P.43- The Battle of Nuremberg- Combat Studies Institute

[16] The Story of a Regiment: A History of the 179th Regimental Command Team

[17] P.47- The Battle of Nuremberg- Combat Studies Institute

[18] www.kriegsende.nuernberg.de/english/chronology/index.html

[19] https://web.archive.org/web/20070520114434/http://www.kriegsende.nuernberg.de/english/chronology/index.html

[20] P.12-14, “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[21] P. 17, “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[22] P.18, “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[23] https://web.archive.org/web/20070520114434/http://www.kriegsende.nuernberg.de/english/chronology/index.html

[24] P.477- The Street Was the One Place We Could Not Go: The American Army and Urban Combat in World War II

[25] P.16- The Battle of Nuremberg. Combat Studies Institute, Ft. Leavenworth, KS

[26] P.14- The Battle of Nuremberg. Combat Studies Institute, Ft. Leavenworth, KS

[27] P.20- “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[28] P.21- “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[29] P.22-26- “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[30] https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/michael-j-daly

[31] https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/us/29daly.html

[32] https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/joseph-f-merrell, 8 APR 2023

[33] P.254-256- The Liberator

[34] P.290- In Pursuit of Hitler: A Battlefield Guide to the Seventh (US) Army Drive (Battleground Europe)

[35] P.290- In Pursuit of Hitler: A Battlefield Guide to the Seventh (US) Army Drive (Battleground Europe)

[36] https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city -of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945.htm

[37] https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city -of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945.htm

[38] https://www.historynet.com/breaking-the-city -of-kings-the-battle-for-nuremberg-1945.htm

[39] P.11- The Battle of Nuremberg. Combat Studies Institute, Ft. Leavenworth, KS

[40] P.36-“The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[41] P.29- “The Operations of Company E, 180th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) in Battle of Nuremberg, Germany, 17-20 April, 1945 (Personal Experiences of a Company Commander)

[42] https://web.archive.org/web/20070525110034/http://www.kriegsende.nuernberg.de/english/chronology/chronology2.html

[43] P.296- In Pursuit of Hitler: A Battlefield Guide to the Seventh (US) Army Drive (Battleground Europe)

[44] P.296- In Pursuit of Hitler: A Battlefield Guide to the Seventh (US) Army Drive (Battleground Europ

[45] P.256- The Liberator

[46] P.19- History, Narrative Form, 157th Infantry Regiment, April 1945

[47] P.28-29- Report of Operations of the 180th Infantry Regiment from 1 April 1945 to 30 April 1945

[48] P.8- 179th Infantry Regiment, Month of April 1945