Battlefield Visit: Hürtgen Forest

/In the fall of 1944, Allied hopes of ending the war in Europe were dashed by series of setbacks. Of these, perhaps none was more futile an effort than the American campaign to take the Hürtgen Forest, located on Germany’s western frontier south of Aachen.

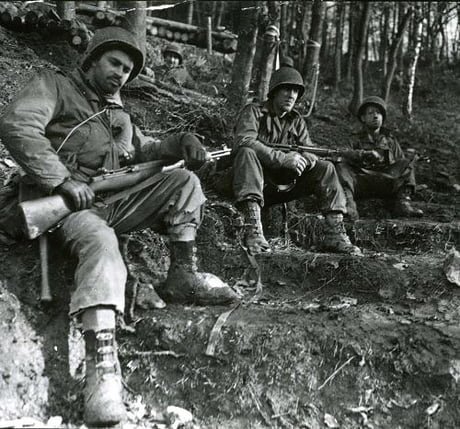

GIs of E Company, 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division move cautiously through the forest south of Germeter during the attack towards Vossenack on November 2nd. Photo: Warfare History Network.

By Seth Marshall

By early September 1944, Allied armies had advanced across France to the frontier of western Germany. Among the Allied armies making their way towards Germany was the American First Army, commanded by General Courtney Hodges. First Army was pushing its way eastward towards the Rhine River, the last major obstacle preventing the Allies from advancing into the industrial heart of Germany. However, in September First Army became bogged down in a major urban battle in the old city of Aachen. To the south of the city lay the Hürtgen Forest (Hürtgenwald in German), a dense forest in very rugged terrain. Hodges believed that the forest was a staging area for German units moving into Aachen. A veteran of the First World War who remembered the terrible fighting in the Argonne Forest, Hodges decided against bypassing the area and instead decided to clear the inhospitable region, perceiving it as a threat to his right flank. There was little pushback against Hodges’ plan to clear the forest- likely this came from the general’s reputation for firing subordinate commanders. During the course of the American involvement in the war in Europe, thirteen corps and division commanders were relieved of their commands; Hodges was responsible for firing ten of them.[1] Hodges’ insistence on taking the area and the reluctance of his commanders to resist the idea was to prove costly; the Hürtgen Forest would be one of the bloodiest battles for American forces in the European Theater.

The Hürtgen Forest occupies an area roughly 11 miles long and 5 miles wide. The forest has been harvested for timber for centuries by German farmers, and much of its neatly ordered trees were described by some as ideal.[2] However, such descriptions ignored the realities of the terrain coupled with the weather of the time. While it is true that much of the forest used for timber is ordered into tidy rows, other parts of the forest are overgrown with brush. The ground rises on steep slopes up to high hilltops and down again into rocky, slippery ravines. In 1944, there were even fewer roads in the area, and those which would have been present would have been little better than logging trails- poor road surfaces for tracked vehicles. By the time the Americans began moving into the forest, autumn was setting in. Cold and wet conditions created fog which persisted late into the morning or set in early in the afternoon. Low clouds and rain also were frequent, which negated the Allied advantage of close air support and often made accurate artillery observation difficult at best. These conditions became deadly when combined with the German defenses in the forest.

In 1938, German engineers had begun constructing concrete bunkers in the Hürtgen as part of the building of the Siegfried Line (known to the Germans as the “Westwall”), the line of defensive fortifications intended by Hitler to protect Germany’s western frontier against invasion by the western Allied countries. After German armies overran France in 1940, construction was halted and much of the guns were removed for use elsewhere. Building resumed in June 1944 after D-Day. Defenses in the Hürtgen were centered around Type 107 concrete bunkers. These bunkers had two machine gun embrasures situated on the bunker’s sides, which were designed to fire into the flanks of an advancing infantry force and form interlocking fields of fire with neighboring fortifications. Some bunkers did have forward-facing machine guns, but these embrasures were protected with metal doors which could open and close as needed. The walls of these bunkers were up to 11 feet thick.[3] The exterior of these bunkers were often painted various shades of green to blend them into their surroundings. Brush and small trees were also allowed to grow on top of the bunkers, and earth was shaped around them to blend them into their surrounding terrain. Inside, these bunkers had enough space for the troops garrisoned inside to sleep, eat and work. They were also stocked well enough to last for days while cut-off from friendly supply lines. Air filtration systems insured that the bunkers were impervious to poison gas, and each bunker was equipped with a heater to keep the occupants comfortable.[4]

Other defenses in the forest included log bunkers hastily constructed from cut timber- while these were clearly not as durable as a concrete position, they blended into their surroundings easily. In some areas, the Germans had also cut down and cleared trees to the front of the bunkers, creating clear fields of fire with no place for advancing infantry to take cover. The Germans also emplaced tank traps, also known as “Dragon’s Teeth”, all along the border region- these 1m x 1m concrete tetrahedrons could not be crossed by tanks and were extremely tough, requiring engineers to use heavy explosives to clear paths through them. Lastly, the Germans had planted hundreds of minefields all along the Siegfried Line and in the forest. In the Hürtgen Forest, these mines were often placed along fire breaks and logging trails, and were often a mix of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. Among American infantry, the Schu-42 anti-personnel mine, made of wood and undetectable by mine sweepers, was particularly feared.[5] Initially, German units in the forest consisted of two depleted divisions, the 275th and 353rd Infantry Divisions, numbering only 5,000 men and lacking any tanks and having little artillery support.[6] Commanding this force was Generalleutnant Hans Schmidt, an experienced infantry officer who had commanded German units in the Polish, French, and Russian campaigns.[7] Eventually, as it became clear that the Americans were determined to clear the forest, additional German units would reinforce Schmidt’s forces.

On September 13th, the fighting for the forest began when the 9th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Louis Craig, began moving into the southern region of the forest with the objective of taking Lammersdorf and the hills surrounding the town. Lammdersdorf was centered across a axis of advance through the forest known as the Monschau Corridor. Within a few days, Lammersdorf was taken, but the hills around the town, in particular Hill 554, were well-defended. Though the 9th Infantry Division had been one of the first US Army units committed to fighting against the Germans in November 1942, the division quickly became bogged down in intense forest fighting. The well-camouflaged emplacements caused large numbers of casualties among the Americans, and German patrols manned by many soldiers familiar with the terrain menaced the GIs. On September 22nd, after receiving artillery and assault gun reinforcements, the Germans launched a counterattack into the 9th Division’s left flank following a 15-minute artillery bombardment. The Germans overran a number of infantry positions and pushed far enough to capture a battery of howitzers. To prevent his division from being completely overrun, General Craig committed the 746th Tank Battalion and 899th Tank Destroyer Battalion to the battle, halting the German counterattack. [8] Hill 554 was not taken until September 29th by Company K of the 39th Infantry Regiment, supported by a platoon of Shermans from the 746th.

Just three days after Hill 554 was taken, General Craig received new orders for his division- he was to continue the attack along the Monschau Corridor with the objective of taking the towns of Germenter and Vossenack. The attack was poorly conceived- still not understanding the logistical nightmare of supplying a division in the forest, the 9th’s three infantry regiments had only two dirt roads that twisted up and down through the heavily-forested hills. It was nearly impossible for tanks to traverse the poor roads, but tank support was vital in order for infantry to succeed against the fortified German positions. The division’s 39th Regiment was to advance on the right, while the 60th Regiment would advance on the left, taking the Schmidt-Steckenborn ridge and creating a three-mile wide gap in the woods. The 47th Regiment was to provide security for the division’s left flank, along with reinforcements to the other two regiments as needed. The 9th was relocated to its staging area, relieving the 4th Cavalry Group on October 2nd. The attack was to begin on the 6th. The attack was preceded by an aerial bombardment from 84 aircraft and an intense artillery bombardment.[9]

Two GIs from 2nd Platoon, D Company, 39th Infantry Regiment provide supporting fire on German positions. Photo: 9thinfantrydivision.net

GIs from the 9th Infantry Division advance through one of the many small villages in the Hurtgen. Photo: 9thinfantrydivision.net

By this time, as it had become apparent to the Germans that the Americans were set on taking the forest, German reinforcements had begun arriving. Defending in the face of the 9th’s attack were soldiers of the 942nd Infantry Regiment and 257th Fusilier Battalion. Even more significantly, the overall German commander in the region, Field Marshal Walter Model, was taking an active role in the battle. Model was a 53-year old career army officer whose highly skilled defensive tactics in the east had earned him the nickname of “Hitler’s Fireman”. Initially, the 9th’s attack proceeded well enough, though slowly. During the first day, most of the units advanced only about 1000 yards, with some battalions suffering significant casualties. However, all units had eventually run up against bunkers with overlapping fields of fire supported by mortars. Some units reached the outskirts of Germeter and placed several elements of the German 253rd Grenadier Regiment in danger of being cut off. As a result, the Germans moved up reinforcements on October 7th which included a mix of second-line infantry, Luftwaffe troops, and police, supported by artillery and anti-aircraft units. With these reinforcements, the Germans launched local counterattacks on the 7th and 8th- both failed in the face of rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire. The second attack had cost the Germans 30 killed and 27 captured, but the attacks did inflict casualties on the Americans.[10] Later in the day, the US 39th Infantry Regiment attempted to resume its advance but only made minor gains before the attack again bogged down. Other American attacks, such as one made with support from tanks and tank destroyers by the 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry Regiment, had better success, advancing nearly to the road junction at Richelskaul. By the end of October 8th, 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry Regiment and 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment had reached the outskirts of Germeter, while 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment had taken Wittscheidt.[11]

On the morning of the 9th, the Germans counterattacked again, preventing the Americans from resuming the advance and retaking Wittscheidt and capturing 41 men from I Company, 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment. On the 10th, additional German reinforcements arrived. The Americans succeeded in taking the village of Raffelsbrand, but the following day were unable to make any good on the previous day’s success. When fire from several bypassed pillboxes prevented reinforcements from moving up, a company from 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment supported by a platoon of tanks from the 746th Tank Battalion began probing towards Vossenack. After just 500 yards, the lead tank of Lieutenant Robert Sherwood was knocked out by a Panzerschreck, and the remaining tanks and infantry withdrew. Near Germeter, the Germans counterattacked with the freshly arrived Regiment Wegelein- some 1800 officers and men. This attack quickly gained ground, pushing into 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment’s positions. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, General Craig dispatched the divisional reconnaissance troop, which was augmented by a platoon of light tanks, along with two companies from the 47th Infantry Regiment. This force finally stopped the German counterattack. The Germans lost 500 casualties in the counterattack, but succeeded in disrupting American designs on Vossenack that same day. After this attack, the surviving officer candidates which made of Wegelein’s unit were withdrawn, further reducing his available strength. Despite this, the Germans continued resisting American advances through the day.[12]

On the 13th, German resistance and counterattacks prevented the 60th Infantry Regiment from making any advances around Raffelsbrand. On the German side of the lines, Wegelein received orders from his superior, Colonel Schmidt, to launch another attack on the morning of the 14th. Wegelein protested these orders strongly, as he had too few men remaining to effectively launch an attack. However, Schmidt accused Wegelein of cowardice, and Wegelein was forced to carry out his orders- he was killed early on the 14th by rifle fire when he strayed to close to American lines while delivering orders to his subordinate officers. In the next day two days, fighting continued to seesaw back and forth, but the 9th Division and its German opponents had been ground down. In close to a month of fighting, the 9th suffered over 4500 casualties, over 1000 of which were the result of sickness, trench foot, injury, and psychosomatic conditions (PTSD). German losses were also high- they had lost some 2000 killed or wounded and over 1300 captured.[13] For all of this bloodshed, the Americans had only advanced some three kilometers.[14]

The large number of noncombat casualties which the 9th suffered spoke to the misery suffered by both sides during the battle. By this time, fall weather had long since set in. Temperatures average in the 40s (Farenheit) dropping into the 30s during this time of year. It rains very frequently, and the wet and cold conditions caused fog and low-hanging clouds to reduce visibility extensively and completely negate the benefit of Allied aircover. The reduced visibility also limited the effectiveness of artillery, since forward observes had problems locating targets and observing the fall of shells. The constant cold and wet conditions had catastrophic effects for infantry living out of foxholes in the forest, who had almost no means of keeping their clothes and socks in particular dry. Winter clothing was also not immediately forthcoming, so the Americans had to make do with the uniforms which they had been wearing since their arrival in mainland Europe during the summer. As if the weather and cold were not enough, at night the forest became virtually pitch dark. The high pines combined with the cloud cover prevented any ambient light from illuminating the battlefield. Paul Boesch, a Lieutenant serving in the 8th Infantry Division and who would move with his Division into the forest in late November, described moving up to the line during nighttime conditions:

“Down the narrow trail of a road between towering trees on either side we moved. The night seemed to get even blacker if that was possible, and the rain came in great wind-driven sheets, drenching every thread of our clothes… The only light came to pierce the blackness came from artillery pieces located in clearings in the forest. The big guns belched their shells with thunderous, unannounced, ear-splitting roars that reverberated against the wooded hills and echoed and reechoed until it seemed we were caught in the middle of some giant cauldron with hundreds of Satanic monsters banging sledgehammers against the sides with fiendish glee. For an instant as each gun fired, the sky would light up with a blinding flash. After the sudden, brilliant burst of light, it was hard to adjust your vision again to the darkness. Circles and stars danced before your eyes, and you had to struggle to keep from losing your balance. Far off on the horizon answering reports from the enemy’s big guns appeared like quick little flickers of heat lighting.”[15]

The Germans were equally miserable, despite their familiarity with the terrain, as evidenced by this excerpt from the German War Diary:

"In the forest itself it looks completely crazy. The trees are leaning on one another through continual fire, and the roads are completely soaked, and everywhere stands water a foot high. The infantrymen look like pigs. No rest for over a week and not a dry thread on their bodies; for it is raining continually and fog is always at hand. It's a bush war: Man against man with enormous efforts for the individual man.... Infantry of the division is completely finished. There are only staffs there, and very few men: Even men who can't be brought forward at the point of a pistol, are also there."[16]

In late October, the 28th Infantry Division replaced the 9th in its positions in the Hürtgen Forest. Commanding the 28th was Major General Norman Cota. At the time, Cota was a rising star in Europe. After serving as the chief of operations for the 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily, and an assignment to Combined Operations in England working on plans for Operation Overlord, he became the assistant Division Commander to the 29th Infantry Division. On D-Day, he earned a Distinguished Service Cross for personally leading survivors of his division off of Omaha Beach, and was subsequently given command of the 28th Division as a reward. However, the Hürtgen would put an end to his sterling reputation.

In mid-October, General Courtney Hodges was informed that his First Army was to provide the impetus behind an offensive into Germany scheduled for the end of the month. Hodges’ objective was the major city of Cologne and the Rhine River, but in order to free up enough forces to carry out the mission, he had to finish clearing out the forest. This task was to fall to Cota’s 28th Infantry Division. Hodges directed Cota to take Vossenack and the treeline facing the village of Hürtgen- a plan which was very close to what the 9th had been ordered to carry out. More ominously, the 28th’s attack was scheduled to begin on October 31st- between then and November 5th, the 28th would be the only unit in the entire 12th Army Group to be attacking along a 150-mile front, a situation which would allow the Germans to mass reinforcements against the Americans in the Hürtgen.[17] Lieutenant General Leonard Gerow, Cota’s superior, tried to allay some of his concerns by reinforcing the 28th with a tank battalion, a towed tank destroyer battalion, a self-propelled tank destroyer battalion, three combat engineer battalions, and a chemical mortar battalion, with additional fire support made available from VII Corps Artillery.[18] The primary focus of the attack was to be first the capture of Vossenack, followed by a crossing of the Kall River gorge, then the capture of Schmidt and its road junction- this attack was to be executed by the 112th Infantry Regiment. Supporting attacks would be carried out by the 110th Infantry Regiment, which was tasked with taking Simonskall and Steckenborn, and by the 109th Infantry Regiment, which was to take the village of Hürtgen. A number of problems began developing as Cota’s staff planned the offensive. Neither Cota nor his staff fully grasped the incredibly difficult nature of the terrain, over which his soldiers would have to advance. Cota also made the mistake of essentially approving avenues of approach centered on one single road for each of his regiments, meaning that all vehicle traffic- supplies, wounded, food, etc., would have to wind their way up and down twisting and turning roads which were at the best of times made of dirt but now were muddy and slippery. Worse still, Cota had not ordered his cavalry units to perform any reconnaissance of the areas where his forces would be moving through, and he consequently was unaware of German forces and dispositions. Based on prior intelligence, Cota and his staff were aware that various elements of thee 275th and 89th Divisions were in the vicinity, but they did not know that the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division had moved up to replace the 89th right as Cota’s division attacked. Lastly, instead of drawing on the experience of the 9th Infantry Division, Cota decided to leave most of his tanks and tank destroyers in the rear for use as artillery. He and his staff believed that the forest and its roads were generally impassable to heavy armored vehicles, but in reality the tanks and TDs could traverse the forest- the lack of their support would lessen the chance of successful infantry attacks against fortifications.[19]

On November 2nd, V and VII Corps Artillery, along with 28th Infantry Division’s own artillery, opened fire at 0800 and began an hour-long bombardment. The artillery fired over 11,000 rounds at both known and suspected German positions. At 0900, the infantry went on the attack. The 109th Infantry Regiment quickly ran into a minefield near Wittscheidt and came under artillery fire. A German counterattack supported by several attacks soon forced the Americans to stop and dig in, unable to take the village of Hürtgen. In the next five days, the regiment suffered 1,275 killed, wounded or missing- a casualty rate of more than 50%.[20] In the south, the 110th had even less success. Both of the attacking battalions encountered stiff German resistance and minefields, forcing them back to their jumping off positions. They attempted to attack several more times during the next ten days, but failed each time. By the time the regiment was replaced on November 13th, every infantry officer in the rifle companies had become a casualty.[21] Only in the center did the 28th have any success. The 112th Infantry Regiment, supported by a company of Sherman tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion pushed through Germeter and took Vossenack, which was lightly defended at the time. This force established a line along the Kall River gorge, but any efforts to venture any further that day were fruitless owing to German small arms fire.

On November 3rd, the commander of the 112th Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Carl Peterson, ordered his forces to bypass the village of Richelskaul and move on to take Kommerscheidt on the opposite side of the Kall River gorge. Despite the muddy trail conditions, his 3rd Battalion encountered little resistance and had secured the town by early afternoon. Leaving his 1st Battalion behind to hold Kommerscheidt, Peterson ordered 3rd Battalion to move on and take Schmidt, which they succeeded in doing after again overcoming light German resistance. Cota ordered Peterson to move his 1st Battalion up to Schmidt to create a stronger line, as he believed that the Germans would counterattack after losing valuable defensive terrain; however, Peterson recommended leaving his units in place to form a defense in depth. This was to prove a mistake- Peterson’s units were overstretched to hold this amount of territory, particularly since both flanks were open due to the failure of the 109th and 110th’s attacks. Peterson’s men, exhausted from their day’s movement over difficult terrain and after having taken two villages, did not dig adequate fighting positions or conceal the anti-tank mines they had positioned properly. Peterson’s forces also didn’t conduct any patrols to establish contact with the Germans, leaving the question of where the Germans had withdrawn to.[22]

During the night, an attempt was made to send additional tanks across the gorge. This came to nothing when one of the tanks nearly fell off a step drop along one of the downward turns along the Kall Trail. Engineers were ordered to try and make the road passable, but no more tanks had crossed by dawn on the 4th. It was around this time that Cota, very pleased with the 112th’s progress the following day, decided to commit his divisional reserve- 1st Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment- to an attack against Steckenborn in an effort to shore up the flank of the 112th’s advance. This attack also quickly bogged down when the infantry ran into a line of pillboxes. Later in the morning, Cota was informed that a tank platoon under First Lieutenant Raymond Fleig had succeeded in crossing the Kall River gorge, but now the trail was blocked by five disabled tanks. One Sherman had hit a mine, another had fallen off the trail, and three others had thrown a track. The disabled tanks would not be cleared until the following day. The news would only get worse for Cota on the 4th.[23]

Thrown tracks from tanks and tank destroyers litter the Kall Trail near Vossenack. Photo: ibiblio.org

A pair of GIs armed with captured German MG42s look out from their foxholes in the forest. Source: Historynet.com

M10s of the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion move along a heavily wooded trail near Germeter. Source: hurtgen1944.homestead.com

At 0700 on the 4th, German artillery opened fire on the 112th’s positions at Schmidt, bombarding the town for half an hour. After the artillery lifted, a two-pronged counterattack began. One force of dismounted German infantry supported by some 15 Panzer III, Panzer IV and Panther tanks advanced on Schmidt from the northeast from Harschiedt; another German force of eight Panthers and four Sturmgeschutz assault guns advanced from the south after staging in Strauch. The mines which the American GIs had placed were easily seen and avoided by the German tankers, who pelted American positions in Schmidt. With no armor support and nothing with which to effectively combat a large armored attack, most of the Americans retreated to Kommerscheidt, though one company withdrew into the woods southwest of Schmidt and was captured several days later.[24] Word of the counterattack was slow to reach American commanders- Peterson was not aware that Schmidt was under attack until 0830, and Cota was not informed until between 0900-1000. By 1130, Schmidt was back in German hands. Cota still had little idea of what was happening on the opposite side of the gorge, and eventually resorted to sending his Assistant Division Commander and assistant G3 to find out what was happening. He also ordered the 1171st Engineer Combat Group commander to clear the Kall Trail by first light on November 5th, even if it meant pushing the Shermans into the gorge. As this was taking place, the Germans continued their counterattack. At 1400, a force of eight Panthers from the 16th Panzer Regiment accompanied by some 200 infantry attacked Kommerscheidt. Lt. Fleig’s recently arrived Shermans were immediately committed to the fight- Fleig’s tank crew knocked out or destroyed three Panthers, a fourth was knocked out by another Sherman, and fighter-bombers took advantage of a gap in the weather to destroy a fifth, after which the Germans withdrew.[25]

On the morning of the 5th, the engineers and tank crews finally got the trail clear- the six other tanks of A Company, 707th Tank Battalion moved up to join Fleig’s platoon at Kommerscheidt, accompanied by nine M-10 tank destroyers.[26] Under pressure from his superiors, Cota ordered LTC Peterson to retake Schmidt. Peterson was prevented from mounting this attack by a second German counterattack, which was halted by the newly arrived armor and by additional close air support provided by fighter bombers. Realizing that Peterson couldn’t retake Schmidt with his available forces, Cota created a Task Force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ripple, who was also commander of the 707th Tank Battalion. Ripple was given the much reduced 3rd Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment, a company of tank destroyers, and two of his own organic tank companies (one medium, one light). The medium company was the Sherman company already in Kommerscheidt, commanded by Captain Bruce Hostrup. Ordered to advance back to Schmidt, Ripple’s force first had to cross the gorge by proceeding along the Kall Trail, which had been partially overrun by the reconnaissance element of the 116th Panzer Regiment. It would take Ripple most of the day to get up to Kommerscheidt.[27]

While Task Force Ripple fought its way up the Kall Trail, a concentrated artillery barrage struck the 2nd Battalion, 112th Regiment in its positions on the Vossenack ridge. Spurred by the artillery and a rumor that German infantry was breaking through, many of the GIs retreated and had to be rallied by their officers. The situation became worse when American artillery, firing back at the German guns, fired a number of rounds short and inflicted numerous casualties among the gathered GIs. To reinforce the now-depleted 2nd Battalion, Cota ordered engineers from the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion to move into the village as ad-hoc infantry. Other engineers were ordered to try and improve the Kall Trail.[28] After making his only visit to the lines on the 6th, Cota requested reinforcements from General Gerow. Gerow shifted the 12th Infantry Regiment from the 4th Infantry Division into the 28th’s sector. The 12th would replace the 109th Regiment, whose 2nd and 3rd Battalions were then ordered to move into Vossenack and the Vossenack ridge respectively.[29]

The next day, November 7th, Cota ordered his Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Davis, to carry out an attack on Schmidt with a Task Force, designated Task Force Davis. This force was to consist of the 1st Battalion, 109th Regiment, which had just received a large number of replacements to make up for its terrible losses in the days immediately prio, along with the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 112th Infantry and 3rd Battalion, 110th Regiment, supported by two tank destroyer companies from the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion and two companies of tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion. While TF Davis might have seemed strong on paper, in reality its elements were severely depleted in combat effectiveness, having all fought in the battle and sustained heavy losses. The armored units were also not up to strength, having suffered their own losses in the fighting previously. It was perhaps for the best when the attack was called off when 1st Battalion, 109th became lost in the forest before the attack. However, elsewhere the Americans continued attacking. Soldiers in the 146th Engineers supported by tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion advanced on and cleared Vossenack of German forces, who left behind some 150 killed and wounded. In Kommerscheidt, the thinly-spred Americans withstood one attack by a German infantry battalion supported by 15 tanks- the American armor supporting the infantry engaged the Germans, knocking out five of the Panzers while losing two Shermans and three M10s. However, after regrouping the German infantry and remaining tanks attacked again and this time they drove the GIs out of Kommerscheidt. The Americans then withdrew to the tree-line behind the village.[30]

As night fell on the 7th, the situation only worsened for the Americans. Vossenack remained in American hands, but only just so. Germans again began attacking the Kall Trail, endangering the Engineers in Vossenack with being cut off. Finally recognizing how badly his Division had faired in the past three days, General Cota called General Gerow and requested to pull his remaining forces in Vossenack back across the Kall River Gorge. He was given permission, but only if his division continued to hold the ridge south of Vossenack and if he sent reinforcements to the 4th Division’s 12th Infantry Regiment, which was preparing to attack Hürtgen. In the wake of the 28th’s failure, several superior commanders visited Cota’s command post, including General Gerow, General Hodges, First Army commander General Omar Bradley, and supreme Allied commander General Dwight Eisenhower. Neither Eisenhower or Bradley remained long; after their departure, Hodges proceeded to reprimand Cota and recommending that Gerow relieve him of command. Gerow did not comply with Hodge’s wishes, but the damage had been done to Cota’s career- he would advance no further beyond his divisional command.[31]

During the remainder of the night, American forces pulled back across the Kall River, and German engineers destroyed the stone bridge over the river, which had been the main way for Americans to get supplies across the river. For the rest of the 28th’s time on the front in the Hürtgen Forest, the division remained relatively inactive. It was relieved from November 14-18th by the 8th Infantry Division. During three weeks in the Hürtgen Forest, the division had been decimated. The 112th Infantry Regiment had gone into the forest with an authorized strength of 3100 men- it suffered over 2300 casualties which included 167 killed outright, 431 missing (most of whom were later listed as killed), 719 wounded, 544 non-battle casualties, and 232 captured. The rest of the division had suffered another 3,868 casualties for a total of nearly 6200. Commanding officers in the division had suffered heavily as well- two of three regiment commanders were wounded, two battalion commanders had to be replaced after suffering from what was then characterized as battle fatigue (more commonly known today as PTSD), a third was badly wounded, and a fourth was killed. Armor losses were heavy as well. The 707th Tank Battalion entered the forest with 50 Shermans and lost 31; the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion came in with 24 M10s and lost 16.[32] After suffering such disastrous losses, the 28th was moved south to a quiet sector where it could regroup- the Ardennes sector. It would face the brunt of the massive German offensive there in mid-December.

Months later in February 1945, as elements of the 82nd Airborne Division and the 78th Infantry Division began pushing into the forest again with the goal of taking the dams along the Roer River to prevent the Germans from opening their gates, the commander of the 82nd, Major General James Gavin made his way through the aftermath of the fierce fighting in November. He later wrote of what he saw.

“One had to be extremely careful because the trail had not been cleared of mines… As we approached the top, all the debris evidenced a bitter struggle. There were more bodies, an antitank gun or two, destroyed jeeps, and abandoned weapons… As evening descended over the canyon, it was an eerie scene, like something from a low level of Dante’s Inferno… During the night, troops were moved up to the town, and I went back down the trail with the leading battalion not long after daylight… A young soldier, a new replacement, was looking with horror at the dead. He began to turn pale, then green, and he was obviously about to vomit. I knew his state of mind: every young soldier, upon first entering combat, is horrified by the sight of the bodies that have been abandoned. They always imagine themselves dead and neglected. I talked to him… and assured him that our outfit never abandoned its dead.”[33]

Many of the bodies had the red Keystone patch on their shoulders, which came come to be called “the Bloody Bucket” thereafter for the division’s struggle in the forest. The 28th Infantry Division had perhaps suffered the most in the battle for the forest, but the fighting was not yet over.

On November 16th, the 4th Infantry Division entered the fighting in the forest with the opening of Operation Queen. Operation Queen was part of a much larger offensive which had as its objective the seizure of crossings across the Rhine River into Germany. To this end, the 4th Infantry Division was to clear the northern portion of the forest which formed the southern flank of VII Corps’ advance. The 4th went into the attack at 1245 on the 14th, making modest gains on the first day. Then on the 17th, the Germans began a vicious defense coupled with local counterattacks which would cause heavy losses to the 4th. On the same day, the 16th Infantry Battalion was able to secure Hill 232, a significant rise in the region.[34] Mines once again caused an extreme headache to the Americans; medics from the 4th Infantry Division had to carry their wounded back some 1500 yards to the nearest aid station because the roads were covered in mines. During the 17-18th, every battalion commander in the 22nd Infantry Regiment was killed or wounded, and the story was much the same for the rest of the division. On November 29th, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 22nd managed to take the village of Grosshau with the aid of tank support. The 22nd lost so many killed and wounded that elements of the 46th Armored Infantry Battalion from the 5th Armored Division assisted the 22nd in follow-on efforts to move up to what would be the 5th’s line of departure for future offensive operations. On December 2nd, a German counterattack hit the 22nd in several places along its line, causing heavy casualties. Losses were severe enough that the division commander, Major General Raymond Barton requested that General Gerow relieve the 22nd. By the end of December 2nd, the 4th Infantry Division had suffered over 4,000 killed and wounded, along with another 2,000 illness-related casualties since November 17th.[35] On December 3rd, the 22nd was relieved by the 330th Infantry Regiment of the 83rd Infantry Division.[36]

A German soldier surrenders to soldiers of the 9th Infantry Division in November near the forest. Photo: warfarehistorynetwork.com

German artillery fires on American positions in the forest. Photo: Bundesarchiv.

PFC M. Berzon, SSG B. Spur and SSG H. Glesser of I Company, 3rd BN, 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, take a brake on the slope of a hill in the forest on 18 November 1944. Source: Realwarphotos.com

M10 tank destroyers of the 803rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, 3rd Armored Division, move along forest trails near Duren on 18 November 1944. Photo: Realwarphotos.com

Further south in the forest, the 8th Division continued its own operations against the Germans. Thanksgiving Day was November 23rd, and the division commander ordered that everyone in his command would receive a hot turkey meal, much to the incredulity of many of the infantry officers and NCOs. Among them was 1st LT Paul Boesch, serving with the 2nd Battalion, 121st Infantry Regiment as a company commander. For much of the day, Boesch and his men were in contact with the Germans. At one point, Boesch received a phone call at his command post. It was a staff officer from his Battalion headquarters who announced, “Happy Thanksgiving. We’ve got hot turkey dinner here for every men in the outfit.” Boesch couldn’t believe what the officer was saying, and tried telling him that his men were too close to the Germans to send up food parties, who had already been up to the line once already that evening; Boesch knew that the Germans would fire on the gathered soldiers as they waited for food. However, his battalion commander was insistent. As predicted, when Boesch’s men began to gather to pick up their share of the turkey dinner, the Germans opened fire with their artillery, killing and wounding several men. Boesch was forced to wait until dawn to send in his medics. When told of the disaster, Boesch’s battalion commander called back to apologize.[37]

Despite this sobering event, the 8th continued pressing forward in spite of dreadful winter conditions which continued to effect the Americans. As with previous divisions assigned to the forest, the 8th saw a large number of its casualties caused because of cold and wet weather injuries, particularly trench foot. George Wagner, a soldier with the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry Regiment, recounted the conditions he experienced in the forest:

“By this time, winter had set in and there was plenty of snow and very cold weather. All movement in our area was held to a minimum as the Germans still indiscriminately dropped shells on us at the slightest movement or noise. As a result, most of our movements were done at night. Supplies were brought up at night to the edge of our wooded area by halftrack. Our area must have seen plenty of action before we got there. There were German bodies lying around. Also the bodies must have been there a long time because they had turned black and there was that sweet smell of death in the air. Occasionally, I would see a G.I. going through the pockets of a dead German soldier, looking for souvenirs. This disgusted me, and I always put a stop to it. Once the sun went down the nights got extremely cold. Rifle patrols went out every night but they never seemed to engage the enemy. A lot of the guys in the company came down with, "Trench Foot" Because of the extreme cold and the restrictions to their being able to move around, ones feet began to swell up so much that they would look as if they were inflated. The feet would swell inside the shoes and some would have to cut or remove shoelaces for relief. In some cases, the G.I.'s boots had to be cut in order to reduce the pressure and the pain. Many of the guys were so bad off that they had difficulty just shuffling about for the bare necessities, food, mail, water, etc. In fact, some of the guys wouldn't even attempt to get out of their Slit-trenches or Bunkers because of the extreme pain they had to endure in trying to walk. Those of us who were still able to get around took care of their needs as best as we could. We brought "K" rations, water and mail to them. The only thing that they ventured out for was the "call of nature".”[38]

The Division was able to retake the village of Hürtgen, though at a heavy cost, with Boesch’s company at the front of the attack. Boesch was soon afterwards injured in a fall, which removed him from his command position for months while he healed. On December 10th, the 2nd Ranger Battalion assaulted and took Hill 400, the largest hilltop in the forest, but then suffered heavy casualties in a German counterattack, but managed to hold on. On the same day, the 9th and 83rd Infantry Divisions, supported by elements of the 3rd and 5th Armored Divisions began yet another attack into the forest- this would prove to be the last major American attack of the battle. Elements of the 9th were able to take the village of Echtz and Merode Castle, which had been defended by paratroopers. The 83rd slogged its way through house-to-house fighting in the towns of Strass and Gey. When a German counterattack supported by panzers hit the 331st Infantry Regiment as it tried to take Gey, the 5th Armored Division’s 744th Tank Battalion was moved forward to stop the attack. Unfortunately, the Battalion became bogged down in mud and mines. Still, the 83rd managed to cling to its gains during the next several days.[39]

Fighting in the Hürtgen Forest came to a temporary end on December 16th when the Germans launched their massive counter-offensive in the Ardennes. The Americans withdrew from the forest to consolidate their lines and shift many of their units to reinforce the areas under German attack. Among the units which were at the receiving end of the initial German bombardment were the 28th and 4th Infantry Divisions, both of which had suffered greatly during the fighting in the forest. While some elements were overrun quickly, others resisted stubbornly as long as they could, which derailed the German timetable for achieving their objectives. Two months after the offensive began and after all of its gains had been reversed by the Americans, the final fighting in the forest took place. In mid-February 1945, the 82nd Airborne Division began attacking through the forest to support the taking of the Rur Dam. The 82nd finally secured the forest on February 9th; the following day, the Rur Dam was secured.[40]

A M3 halftrack with the 16th Infantry Regiment moves through a muddy track in the forest in February 1945 as the 82nd Airborne moves into the forest. Source: Wikimedia.

In five months of fighting, American casualties had amounted to 24,000 killed, wounded or captured, plus another 9,000 casualties related to trenchfoot, illness, and combat fatigue. The Americans had also lost dozens of tanks and tank destroyers in the fighting. The Germans had lost approximately 28,000 total casualties.[41] While the Rur dam was eventually secured, it came at an extreme cost. Several American commanders, including Bradley and Eisenhower, barely mentioned the battle in their post-war memoirs, despite the length of the battle and its heavy toll. Several postwar historians wrote that the battle had been a futile one which should not have been fought. At the very least, after attempting to take the most direct route to the Rur Dam and discovering that taking that route required crossing inhospitable terrain which favored the defensive and whose defenders were familiar with the terrain, it would have been more advisable to bypass the Germans in the forest. American commanders at the time believed that doing so would have left an open flank which invited German counterattack. There is a degree of truth to this, but at least initially German forces in the forest were relatively thin, and it is possible that the Americans might have been able to move around the weakly-defended sector while leaving a fixing force in place. However, this is speculative and the outcome of such a move will never be known. What is certain is that the manner in which American commanders repeatedly committed their infantry into frontal assaults against a well-emplaced defender bordered on incompetence, especially given the fact that many of them never bothered to walk the terrain that their men would be moving through.

Usually when visiting a battlefield, I try to visualize the area as it might have looked when the battle occurred. Sometimes this is difficult, as towns have expanded and altered the landscape. The terrain itself might have been altered time or man for one reason or another. However, in some cases the terrain of a battlefield remains the same and leaves an immediate impression on the observer. Hürtgen Forest is such a place. Situated along a series of steep hills and deep gorges around the Rur River and Kall River, the forest still remains dense and foreboding. On the weekend of I visited, I arrived in the town of Vossenack, parked my car and set off towards the west where the forest lay. After walking across a field which sloped down towards the Kall Valley, the relatively flat ground gave way to a steep drop-off towards the valley floor, which itself was not very wide. The Kall River runs through the gorge; a stone bridge forms the main crossing point across the river. On this bridge is a monument called “A Time for Healing.” This monument was built in recognition of the efforts of one Captain Günter Stüttgen, a regimental doctor with the German forces, who negotiated an unofficial ceasefire with American forces to attend to the thousands of wounded on both sides. The ceasefire last for five days, during which American and German medics at times worked alongside one another. The monument was designed by Michael Pohlmann and put in place in the mid-2000s.[42] On the other side, the terrain rose up again sharply, covered in dark pine trees. Today, in many places parts of the woods have been cleared to make room for wind turbines or paved roads, but most vehicle paths remain little more than single lane dirt roads which may have gravel in some locations. These paths wind their way steeply up both sides of the valley- incredibly, it would have been these paths along which the Americans sent Shermans and M10 tank destroyers- small wonder that so many became immobilized by the terrible terrain.

After a steep hike across the Kall Valley and up the other side, I found myself in the depths of the forest. Wandering off of paths, the pine trees grew dense- it was difficult to walk on ground that was not made more rough by tree roots and rocks protruding from the surface. On the days which I visited the forest there was no fog, but it’s easy to imagine visibility decreasing to near zero even during daylight hours. Having spent time in the woods elsewhere in Germany in poor weather or night conditions, it’s also very easy to imagine how impenetrable the darkness of night would have been in October and November 1944, particularly when fog or mist descended into the woods. In a number of places throughout the woods, and especially all along the western ridge along the Kall Valley, numerous foxholes remain, along with shell impacts. At the time I visited the Hürtgen Forest, I had visited Verdun just weeks earlier. The shell impacts were less numerous than Verdun, and generally not nearly as large, but there are enough remaining to still indicate the ferocity of the indirect fires which were used during the battle. Unlike Verdun however, Hürtgen Forest saw widescale use of treebursts, which are no longer evident.

In several places throughout the forest, grave markers remain from where the bodies of soldiers were discovered long after the fighting had ended. In several cases, the dead soldiers were found 40-50 years after the battle had ended; the messages left behind by families on the markers are incredibly tragic, made worse by the thought of one’s loved ones being left seemingly forgotten in the thick forest. In another location, on the western slope of the Kall Valley, the melted rubber tracks of a Sherman tank remain seared into the ground where it was hit and burned.

The most ominous features of the Hürtgen battlefield which remain today are the bunkers. In the area I visited, there is a trail which takes the visitor to a series of bunkers on the western ridge of the Kall Valley. The bunkers are almost impossible to see from much further than 50-60 meters away, by which time most soldiers would be in the middle of overlapping fields of fire from machine guns or rifles. The bunkers are blended into the terrain-earth has been mounded along their flanks to cleverly conceal them among their surroundings. Making them even harder to see is the camouflage paint, which while faded today still makes them difficult to discern. It’s not hard to see why GIs struggled so much to make it past these fortifications. Well-camouflaged and difficult to bring heavy fire on because of the terrain, a decently-equipped German infantry squad could hold a bunker successfully against a much larger force. Making matters worse for an attacker is the fact that neighboring bunkers lay only 100 meters or so apart. Most of the bunkers today are not well-maintained inside- stagnate pools of water are inside many rooms, and exposed steel has rusted severely in many places because of the humidity. However, many bunkers are also easily accessible, so it’s possible for a visitor to gain a sense of what the defenders might have seen from their vantage point. In several cases, bullet pockmarks or impact marks from artillery or tank fire on the bunker exteriors testify to their strong construction.

The Hürtgen Forest remains an imposing sight over 76 years after the fighting which took place there. The terrain is striking, as are the many bunkers which remain behind. The battlefield is also marked by several tragic memorials, including the odd marker to a long-forgotten soldier whose body was not found until years after the war had ended. To a visitor in the region, I would strongly recommend taking the time to make the trip to the battlefield to better understand what the soldiers on both sides were going through in the fall and winter of 1944.

While much of the forest has been overcome by development, the rest of the Hurtgen remains and imposing place. Photo: Author.

Several graves of soldiers found years after the fighting ended are scattered throughout the woods. Photo: Author.

Text from the marker for PFC Robert Cahow, a GI with the 78th Infantry Division who was killed and listed as missing for years after the battle had ended. Photo: Author.

Though they are now covered in over 70 years of growth, the bunkers remain and imposing site which blend into their surrounding terrain. Photo: Author.

Battle damage from the fighting remains evident on the outsides of bunkers even today. Photo: Author.

Many bunkers were blown up by Allied soldiers to prevent the Germans from reoccupying them. The area around these bunkers is being used for wind farms. Photo: Author.

The front of a blown-up bunker, which still shows the original camo pattern from the 1940s. Photo source: author.

The insides of several bunkers, which were designed to keep intruders out for a significant period of time, also show battle damage from the fighting. Photo: Author.

In the region surrounding the battlefield, miles of Dragon’s Teeth anti-tank obstacles remain in place where they were laid years again.

More Dragon’s Teeth. Photo: Author.

A view of the Kall River gorge, looking east from Vossenack. Photo: Author.

The Kall River bridge, one of the only significant bridges which could take the weight of tanks within the region. Photo: Author.

A statue called “A Time for Healing”, which was installed in the 2000s by a German sculptor on the Kall River bridge. Photo: Author.

One of the switchbacks in the Kill River trail, which proved such a major obstacle for US tanks and tank destroyers to navigate. A picture showing M-10s maneuvering along the trail shows a similar switchback. Photo: Author.

The tracks from a Sherman or M-10 which melted to the rock when the vehicle was destroyed in 1944. Photo: Author.

Sources

1. Atkinson, Rick. “The Hürtgen Forest, 1944: The Worst Place of Any.” HistoryNet, 7 May 2013, https://www.historynet.com/the-hurtgen-forest-1944-the-worst-place-of-any.htm.

2. “The Siegfried Line.” Museum of Military Memorabilia in Naples Florida, 20 Oct. 2015, https://www.museum-mm.org/the-siegfried-line/.

3. “Hurtgen Forest.” 9th Infantry Division in WWII, 11 Oct. 2021, https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/.

4. Scorpio. 275th Infantry Division (15 Sep - 1 Oct 1944 ) by Hans Schmidt, Generalleutnant A.D., 18 July 2015, http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/hans-schmidt-fms-b373-2.html.

5. Bell, Kelly. “Costly Victory in Hürtgen Forest.” Warfare History Network, Sovereign Media, 6 Nov. 2020, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/.

6. Boesch, Paul. Road to Huertgen: Forest in Hell. Gulf Publishing Company, 1962.

7. Memories of Hubert Gees - Schlacht Im Hürtgenwald, Scorpio, 7 July 2015, http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/memories-hubert-gees.html.

8. Bradbeer, Thomas G. “Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?” Army History, pp. 18–41. Published by U.S. Army Center of Military History

9. Gavin, James M. “Bloody Huertgen: The Battle That Should Never Have Been Fought.” American Heritage. Vol 31, Issue 1 (December 1979).

10. Rush, Robert S. “Hell in the Forest: The 22d Infantry Regiment in the Battle of Hurtgen Forest.” The National Museum of the United States Army, The Army Historical Foundation, 2021, https://armyhistory.org/hell-in-the-forest-the-22d-infantry-regiment-in-the-battle-of-hurtgen-forest/.

11. Schindler, John R. “Remembering Thanksgiving in Hell.” Observer, Observer, 24 Nov. 2017, https://observer.com/2017/11/remembering-wwiis-hardest-fought-battle-100k-dead-at-hurtgen-forest/.

12. Wagner, George. “Recollections of George Wagner - Huertgen Forest Battle.” Edited by Scorpio, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 9 July 2015, http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/recollection-george-wagner.html.

13. Bayer, Craig. “The Huertgen Forest: A Necessary Battle.” Loyola University, 2002.

14. Streeter, Timothy S. “The Battle of the Hurtgen Forest.” Modelling the US Army in WWII, 2007, http://www.usarmymodels.com/MODEL%20GALLERY/Hurtgen%20Forest/2history.html.

15. “Kall Bridge.” Liberation Route Europe, Liberation Route Europe/Cultural Route of the Council of Europe, https://www.liberationroute.com/pois/237/kall-bridge.

[1] https://www.historynet.com/the-hurtgen-forest-1944-the-worst-place-of-any.htm

[2] https://www.historynet.com/the-hurtgen-forest-1944-the-worst-place-of-any.htm

[3] https://www.museum-mm.org/the-siegfried-line/

[4] https://www.museum-mm.org/the-siegfried-line/

[5] https://www.historynet.com/the-hurtgen-forest-1944-the-worst-place-of-any.htm

[6] https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/

[7] http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/hans-schmidt-fms-b373-2.html

[8] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/

[9] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/

[10] https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/

[11] https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/

[12] https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/

[13] https://9thinfantrydivision.net/battle-of-the-hurtgen-forest/

[14] https://wwwhistorynet.com/battle-of-hurtgen-forest-for-schmidt-and-kommerscheidt.htm

[15] P.143-144- Road to Huertgen by Paul Boesch

[16] http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/memories-hubert-gees.html

[17] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[18] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[19] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[20] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[21] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[22] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[23] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[24] Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[25] P.21- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[26] P.22- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[27] P.23-24- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[28] P.25- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[29] P.26- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[30] P.27-29- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[31] P.29- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[32] P.30-31- Major General Norman Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?

[33] https://www.americanheritage.com/bloody-huertgen-battle-should-never-have-been-fought

[34] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/

[35] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/

[36] https://armyhistory.org/hell-in-the-forest-the-22d-infantry-regiment-in-the-battle-of-hurtgen-forest/

[37] https://observer.com/2017/11/remembering-wwiis-hardest-fought-battle-100k-dead-at-hurtgen-forest/

[38] http://home.scarlet.be/~sh446368/recollection-george-wagner.html

[39] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2018/12/15/costly-victory-in-hurtgen-forest/

[40] The Huertgen Forest: A Necessary Battle

[41] http://www.usarmymodels.com/MODEL%20GALLERY/Hurtgen%20Forest/2history.html