Tools of War: M1 Garand

/A GI poses with an early production M1 Garand in a rare pre-war color photograph taken at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Source: Popular Mechanics/Library of Congress.

In the mid-1930s, the US Army found itself searching for a new main battle rifle for its soldiers. The aging Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifle was still the primary firearm of the infantry, but there was a growing trend towards the development of semi-automatic rifles. However, Springfield engineer John Garand had been working on a solution for years which would eventually take shape as the US Army’s primary small arm during World War II.

By Seth Marshall

During the Second World War, nearly all of the countries involved used bolt-action rifles as their primary rifle. These weapons had been developed either late in the 19th Century or not long after the turn of the century. Britain had the Lee-Enfield, Germany had the Kar 98, the Soviet Union had the Moisin-Nagant, and Japan had the Arisaka. However, during the decades preceding the war, a number of countries had experimented with semi-automatic weapons. In the United States, an immigrant weapon engineer named John Garand had been refining the design of a new rifle which would eventually be adopted for use by the entire US military.

John Cantius Garand was born on January 1, 1888 in the small town of Saint-Remy, Quebec in Canada. In 1898, Garand’s family moved to the United States, to Connecticut. Garand only attended school for another year until age 11. Following this, he began working in a local textile mill, gaining experience in took-making with the machinists there. A few years later, he began working at Brown and Sharpe, a tool-making company in Providence, Rhode Island. By the time of the First World War, Garand had moved to New York. When the Army began looking to design a new light machine gun, Garand took an interest. Garand began a partnership with another firearms designer, John Kewish. Kewish paid Garand $50 a week for his work; by June 1918, they had a prototype ready to be demonstrated. After showing their weapon to Hudson Maxim, the brother of machine-gun designer Hiram Maxim, Hudson recommended that the two men demonstrate their prototype t the Naval Consulting Board. Though the board passed them along to a succession of military agencies, the design was ultimately turned down. However, the Naval Consulting Board did send Garand and Kewish to the National Board of Standards, which began paying Garand and a different machinist $35 a week to improve his existing design, using NBS facilities.[1] Garand began his work in August 1918; by the time he had completed the requested modifications, it was 1919 and the First World War had ended.

John Garrand at work in the Springfield Armory machine shop in 1923. Photo source: m1-garand-rifle.com

Despite the initial setback, Garand’s talent for weapons design apparently did not go unappreciated. In November 1919, Garand was hired by Springfield Armory. By this time, Garand had become a naturalized citizen. Additionally, recognizing that semi-automatic rifles would represent an advantage for US infantrymen in future wars, the Army continued to press forward with the development of a new primary rifle. While Garand continued work on his design, another weapons designer was busy on his own semi-automatic creation. John D. Petersen had diverted from the Army’s M1906 .30-06 cartridge by developing a .276-caliber cartridge and compatible toggle-action rifle. Pedersen’s rationale for the change in ammunition was that an infantryman equipped with such a weapon would not have to carry as heavy a rifle and could instead carry more rounds.[2]

Through the 1920s, changes in Army requirements kept both men making changes to their respective designs. Garand’s rifle, initially a primer-operated designed, was changed first in 1925 to chamber the new M1 .30 cal cartridge and was gas-operated, then to a .276-caliber design in late 1927 to compete with Pedersen’s rifle. Finally, in the early 1930s, formal trials were held to determine which rifle was more suitable. The Garand, by now designated as the T3E3 was determined by the Ordnance Department in January 1932 to be better suited for the next war than the Pedersen. However, not long after the competition, the Army decided that it would not convert to .276-caliber, instead preferring to remain with the already existing M1 .30-06 cartridge, which was readily available in large quantities. The newly redesigned rifle was the T1E2.[3] 80 production models of this new rifle were ordered for testing in March 1932, but it was some time before machinery had been constructed and the rifles built. As a result, the first production T1E2s were very expensive for the time- over $1800 per rifle (over $31,000 in 2018).[4] By the time the rifles had been produced and sent to Aberdeen Proving Grounds in August 1934, the design had been redesignated the M1. During the next year and a half, the rifles were shunted back and forth between the proving grounds and Springfield Armory as deficiencies were worked out of Garand’s design. Finally, on January 9, 1936, the M1 was officially approved for use in the Army by the Adjutant General and redesignated “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1.”[5] The approved design of the M1 had resulted in a rifle weighing nearly 11 pounds (4.9kg) and 43 inches in length. The new rifle had an effective range of 457 meters, and a well-trained infantryman could fire it up to 30 rounds per minute.[6]

The final product of John Garand's labors. Photo source: Wikipedia.

John Garand shows the details of his rifle to Major General Charles Wesson, Chief of the Army Ordnance Corps. Photo Source: Wikipedia.

The first production M1s began coming of the lines at Springfield Armory in August 1937. Deliveries were somewhat slow at first- 945 were handed over to the Army in 1937, and 5,879 in 1938. Daily production rates steadily rose however; in 1937, only 10 were produced every day- by January 1940, 200 were being turned out by Springfield Armory daily. The first M1s were not perfect. It was quickly found that the gas cylinder assembly and muzzle plug were too loosely fixed to the barrel, which affected accuracy. Additionally, early M1s were prone to jamming after firing six rounds. Investigations found that there were manufacturing problems with guiding ribs in the receiver, leading to stoppages. Not helping matters was bad press- during the 1939 National Matches at Camp Perry, Ohio, 200 M1s had been supplied to participants. When many of the contestants complained of problems with the rifles, the Army denied that there were problems with the rifles. However, the issues were resolved in time. In late 1939, a new gas system was developed and implemented by the fall of 1940. 50,000 M1s had been produced prior to the change.

A magazine photograph shows the difference between the early "Gas-trap" M1s and later production versions. Photo source: American Rifleman.

With the bugs gradually being worked out of the design, production of the M1 increased as the likeliness of war increased. Winchester Repeating Arms Company began producing M1s under license in 1940, delivering its first rifles in December that year. The M1’s introduction to combat came when the Japanese invaded the Philippines in December 1941. Several examples were being used by American soldiers defending the islands, including M1s which had the older-style gas-trap. Despite concerns that the older versions would be more seceptible to breaking down or stoppages, General Douglas MacArthur sent a cable in February 1942 to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that,

“Garand rifles giving superior service to Springfield, no mechanical defects reported or stoppages due to dust and dirt from foxhole use. Good gun oil required as lubricant to prevent gumming, but have been used in foxhole fighting day and night for a week without cleaning and lubricating. All these weapons are excellent ones even without any modifications such as suggested.”[7]

With the declaration of war, the production of M1s was stepped up significantly. By the end of the war, over 4,000,000 M1s were produced by Springfield and Winchester.[8] Garand’s rifle had become revered by soldiers and marines alike by that point. The rifle was so good that General George S. Patton remarked in January 1945 that the M1 was “the greatest battle implement ever devised.”[9] In addition to the standard M1 rifle, sniper variants were produced in large quantities- by 1944, the M1C replaced the M1903A4 as the US Army’s standard sniper rifle.[10]

An NCO instructs a private on marksmanship during the Second World War. Photo source: Popular Mechanics/Getty Images.

A World War II poster featuring the M-1. Photo source: m1-garand-rifle.com

John Garand poses with an M1. Photo: Popular Mechanics.

A soldier with his M1 in Europe. US soldiers and marines enjoyed a firepower advantage over their adversaries in both Europe and the Pacific; all of the Axis powers used primarily bolt-action rifles such as the Kar 98K and the Arisaka. Photo source: Popular Mechanics.

During the years immediately following the end of World War II, production of the M1 tapered off, and many wartime rifles were placed in storage. However, when North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, production was ramped back up. International Harvester Corporation and Harrington & Richardson Arms both took up M1 production during the 1950s- between 1950-1957, another 1,500,000 M1 rifles were produced.[11] Many M1s began equipping other nations’ armies, including those of Germany, Italy, and Japan, which the M1 had helped defeat just years earlier. However, by the mid-1950s, the M1’s days were waning.

The development of the M14 had begun years before it was formally adopted by the Army in 1957. Equipped with a 20-round magazine and chambered in 7.62 x 51mm NATO, the M14 had drawn upon the M1 design. Deliveries of these rifles began in 1959, and the transition from M1 to M14 within the Army was completed in 1963. Use of the M1 in the Army Reserve and National Guard, and US Navy continued into the 1970s. [12]

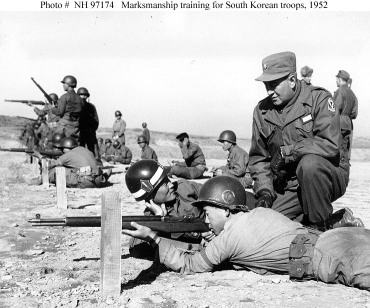

US soldiers supervise the marksmanship training of South Korean soldiers using M-1s in 1952. Photo: Wikipedia.

In spite of the success of his rifle, John Garand never received profits from his design, having sold the patents to Springfield Armory. During his 34 years working in conjunction with the Ordnance Corps, Garand never made more than $12,000 annually. At one time, a bill to award him with $100,000 for his services was introduced into Congress, but it failed to pass. In 1941, he was awarded the Medal for Meritorious Service, and in 1944 he was awarded the Medal for Merit. [13] He continued working for Springfield Armory until his retirement in 1953. John Garand died in 1974 at the age of 86 in Springfield, Massachusetts.[14]

The M1 Garand was one of the seminal rifles of the Second World War, and remains a classic weapons design. Reliable, tough, and efficient, the M1 was a favorite of soldiers and marines alike. It influenced the design of subsequent rifles, including the M14. Today, thousands of M1s remain in private hands as popular collectors firearms.

John Garand after his retirement. He died in 1974 in Springfield, Massachusetts. Photo: m1-garand-rifle.com

Sources

1. “M1 Garand History - John C Garand, The Inventor.” The M1 Garand Rifle, m1-garand-rifle.com/history/john-garand.php. Accessed 5 May 2018.

2. Canfield, Bruce N. “The Unknown M1 Garand.” American Rifleman, Jan. 1994. https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand . Accessed 5 May 2018

3. “M1 Garand Rifle.” D-Day Overlord, 2018, www.dday-overlord.com/en/material/weaponry/m1-garand-rifle. Accessed 5 May 2018

4. Seijas, Bob. “History of the M1 Garand Rifle.” Garand Collectors Association, 2018, thegca.org/history-of-the-m1-garand-rifle/. Accessed 5 May 2018

5. Moss, Matthew. “The Legendary Rifle That Fought World War II.” Popular Mechanics, Hearst Communications, 30 Dec. 2016, www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a24537/m1-garand-world-war-two. Accessed 5 May 2018.

6. “M1 Garand History – The M1 Garand After 1957.” The M1 Garand Rifle, https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/since-1957.php. Accessed 5 May 2018.

7. “M1 Garand History - John C Garand, The Inventor.” The M1 Garand Rifle, https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/world-war-ii-to-korea.php . Accessed 5 May 2018.

[1] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/john-garand.php

[2] https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand

[3] https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand

[4] https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand

[5] https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand

[6] http://www.dday-overlord.com/en/material/weaponry/m1-garand-rifle

[7] https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2015/9/15/the-unknown-m1-garand

[8] http://thegca.org/history-of-the-m1-garand-rifle/

[9] http://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a24537/m1-garand-world-war-two

[10] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/john-garand.php

[11] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/john-garand.php

[12] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/since-1957.php

[13] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/world-war-ii-to-korea.php

[14] https://m1-garand-rifle.com/history/world-war-ii-to-korea.php