Tools of War: The Northrop P-61 Black Widow

/The Northrop P-61 was the first American aircraft designed exclusively for night combat, and though it arrived later in the war, it proved itself a very capable combat aircraft.

by Seth Marshall

The P-61’s design had its origins in 1940, when the British were looking to the US aircraft industry for an aircraft capable of intercepting and shooting down German bombers targeting London with night raids. The U.S. Army Air Corps decided that they too were in need of an aircraft capable of a similar mission. Northrop began designing the night-fighter around a large twin-tail boom design powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial engines, each providing 2,000 horsepower. The fuselage provided space for three crew; a pilot, a gunnery officer, and radar operator. The aircraft was armed with four 20mm cannons mounted in a bay below the cockpit, and four .50 caliber machine guns housed in a turret on top of the fuselage. Most importantly, the new night fighter was designed to carry the SCI-720 AI radar set, which was capable of detecting enemy aircraft in nearby airspace.

After a lengthy period of design, the prototype XP-61 first flew on May 21, 1942. Despite being such a large aircraft, the P-61 proved that it “had very good maneuverability, in part because of the patented spoiler type later control and deceleration/airborne surfaces.”[1] Two years later, after flight testing, the P-61 entered service in Europe with 422nd Fighter Squadron, stationed at Charmy Down, England. Initially, pilots were unconvinced that such a large aircraft would be able to hold its own in aerial combat- a Northrop test pilot travelled to training bases, providing air show demonstrations with the P-61 and proving that the aircraft was more than capable of holding its own in a dogfight.[2] In the end, several squadrons of P-61s in Europe and 8 squadrons of P-61s in the Pacific had taken charge of night-time aerial combat.

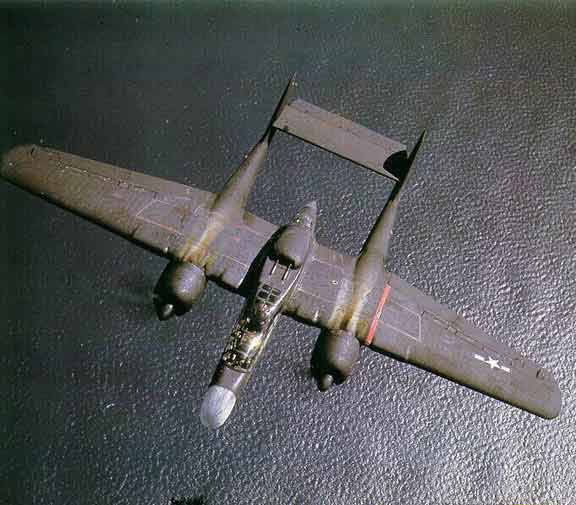

A P-61 based in England in 1944.

A P-61 based in the Pacific Theater.

Early experience with the P-61 showed that the top turret of the P-61 caused rough air flow which disrupted normal flight enough that turrets were removed from all P-61As. Most squadrons in Europe would experience shortages of spares, reducing the number of P-61s available for missions. Despite this, European squadrons were assigned not only for night patrols but also night ground attack missions, something that the P-61 proved to be well-suited for, since it was capable of carrying some 6,400lbs of ordnance or extra fuel tanks on its wings. And despite its late arrival in the war, squadrons equipped with the P-61 racked up a number of kills. The 425th Fighter Squadron shot down 10 aircraft along with four V-1 flying bombs, while the 422nd claimed 43 aircraft destroyed and 5 V-1s shot down, making it the highest-scoring P-61 squadron.

In the Pacific, the 6th and 419th Night Fighter Squadrons were the first units in the Pacific to receive the aircraft. By the end of the war, the 6th NFS had claimed 16 kills, making it the highest-scoring P-61 unit in the Pacific. Black Widows were also used for ground attack missions in the China-Burma-India theater, attacking convoys attempting to resupply Japanese units. In the Mediterranean, the P-61 equipped the 414th, the 415th, the 416th, the 417th, and the 418th Night Fighter Squadrons. Of these, only the 414th saw combat, with a detachment from the 414th being sent to Belgium to provide support during the Battle of the Bulge- this detachment claimed 5 enemy planes shot down.[3]

By the end of the war, 941 P-61As,Bs, and Cs had been built, along with 38 F-15 Reporter aircraft, a modified version of the P-61 designed for reconnaissance. P-61 units claimed 109 aircraft shot down in total during the war. After the surrender of the Japanese, P-61s were gradually replaced by the newer F-82 Twin Mustang. Some were used in early ejection seat experiments, while others were used in a large project carried out by the US Air Force to gather information about thunderstorms. The last P-61 was retired in 1953. Today, of the 900+ P-61s and F-15s built, only four remain. P-61B Ser. No. 42-39715 is on display at the Beijing Air and Space Museum. P-61C Ser. No. 43-8330 is on display at the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia. P-61C Ser. No. 43-8353 is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. Finally, P-61B Ser. No. 42-39445 is being restored to flying status by the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania.

The Mid-Atlantic Air Museum's P-61B, which is currently being restored to flying status. Photo credit Mid-Atlantic Air Museum. Photo credit Mid-Atlantic Air Museum.

[1] P. 139- Gunston, Bill. The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II. New York: Prentice Hall, 1988. Print

[2] P.11-12 Thompson, Warren E. P-61 Black Widow Units of World War 2. Botley, Oxford: Military Book Club/Osprey, 2000. Print

[3] P.50 Thompson, Warren E. P-61 Black Widow Units of World War 2. Botley, Oxford: Military Book Club/Osprey, 2000. Print