Submarines in the Pacific War Part II

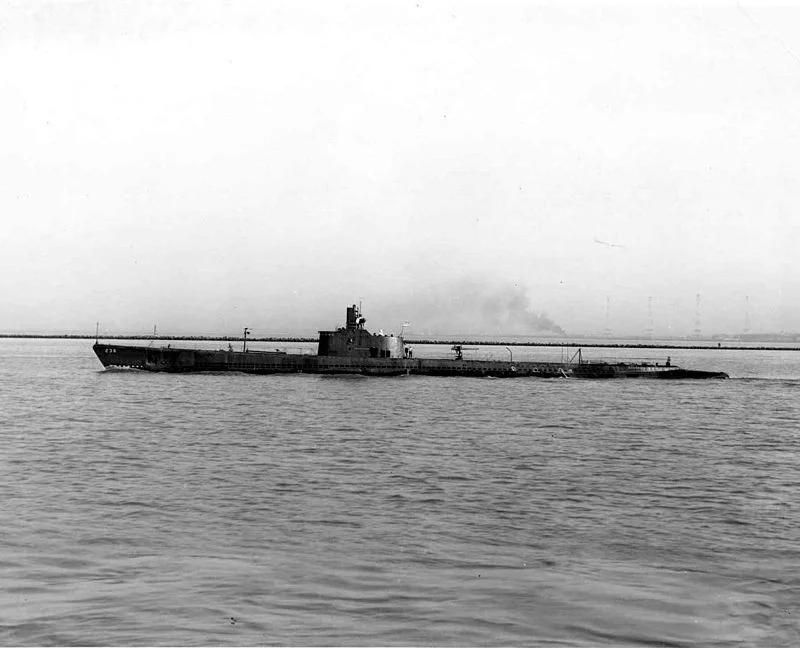

/In the previous part, I discussed submarine design of both the US Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy. In this conclusion, I will discuss how the US Navy succeeded in its campaign against the Japanese merchant fleet, and why the Japanese struggled to find success with their submarines.

One of the most important factors in the US Navy’s success was the renouncement of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, which forbade navies from implementing unrestricted submarine warfare against their opponents. While outwardly US Navy doctrine had held the submarine in a scouting role to the main surface fleet, submariners had always been loath this concept. As war approached, submariners made reports and published doctrine which took their boats away from the surface fleet and target enemy shipping and warships while operating independently.[1] This doctrine would be affirmed mere hours after Pearl Harbor when Admiral Harold Stark ordered all US submarines to engage in unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. While it violated the terms of the London Naval Treaty and caused the deaths of thousands of Japanese sailors (as well as Allied POWs aboard some Japanese ships), the change in doctrine had a devastating affect upon Japan’s ability to resupply its Pacific outposts, to such an extent that it turned to its own submarines to fill the gap left by sunk transports.

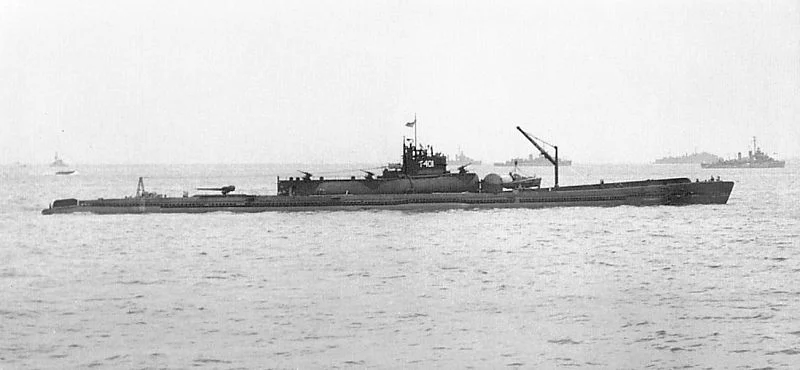

While the US Navy promptly changed its stance on the role of its submarines in battle, the IJN did not. The IJN preferred to adhere to its General Battle Instructions from 1934, which read “Submarines are deployed effectively for the purpose of achieving their main goal: surprise attack on the enemy’s main force.” As the war progressed, submarine duties were clarified in the Combined Fleet’s Tactical Instructions of 1943, which detailed the specific roles of submarines. “Submarines, aided by naval aircraft, reconnoiter enemy bases or anchorages. If the enemy sorties, submarines and aircraft attempt to intercept the enemy fleet and maintain contact.”[2] The later set of instructions is remarkable given its release date- by this point in the war, the Japanese would be all too well aware of the effects of American submarines on their shipping. IJN submarines experienced some success using their battle doctrine during 1942, when they sank a number of Allied warships (including the memorable attack by the I-168, which sank both the carrier USS Yorktown and the destroyer USS Hammann). However, their successes fell off dramatically as the Allies became more adept at detecting and sinking submarines and as IJN submarines were increasingly shifted to other missions. Early in the war, submarines were frequently used as platforms to launch aircraft on reconnaissance flights over US territory. On one occasion, a floatplane was launched from a submarine carrying incendiary bombs with the purpose of starting forest fires in Oregon. Submarines also used their deck guns to shell various industrial facilities along the West Coast and military structures on Midway Island on several occasions, with little to no results. Later in the war, submarines would again become launch platforms for attacks on US installations, this time through the use of midget submarines and Kaitens (one-man kamikaze submarines). These attacks also had little effect on the Allies, and were ultimately did more harm than good to the IJN as the slow carrier submarines were frequently detected and destroyed before launching their kaitens. The severe effects of the US submarine campaign on Japanese shipping forced the IJN to find alternative means of getting supplies to the front lines and garrison islands scattered throughout the Pacific. Consequently, submarines were frequently relegated to carrying supplies and troops rather than being used to hunt for Allied ships.

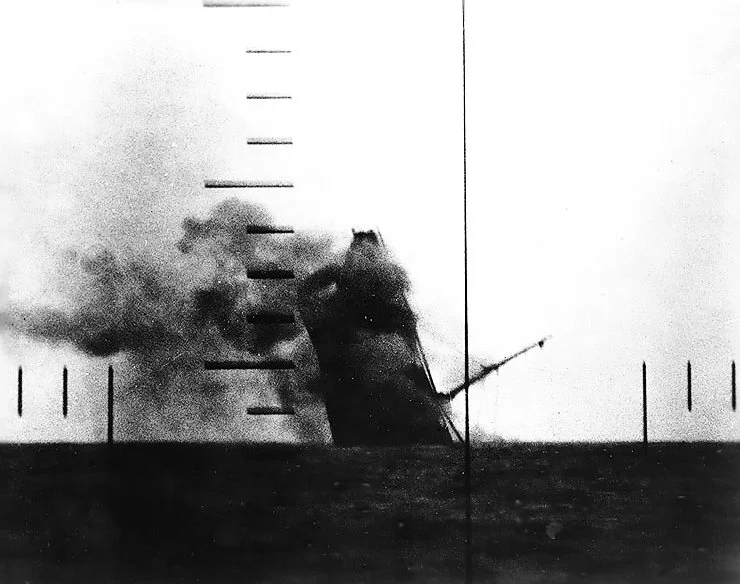

The shift in doctrine on the part of the US Navy paid off, as evidenced by postwar analysis conducted by the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee, which was created to examine IJN and Japanese maritime fleet losses. Initially, Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood, commander of the US submarines in the Pacific, estimated that the vessels under his command had sunk roughly 4,000 ships for 10 million tons. Analysis by JANAC reduced this figure to 1,314 ships sunk for 5.3 million tons. Despite this greatly reduced figure, the American submarines were responsible for the sinking of an astounding 55% of all Japanese vessels lost during the war. [3] This figure included the loss of 1,113 merchant ships for 4.9 million tons of merchant shipping (60% of all Japanese merchant ships sunk) and 201 warships for 540,000 tons. Among the warships sunk were eight aircraft carriers of varying types, one battleship, and eleven light and heavy cruisers. The JANAC group also credited submarines as “probably” having sunk an additional 78 ships for 263,306 tons. By comparison, the carrier aircraft of the US Navy sank 2 million tons of shipping, roughly half of which was IJN vessels.[4]The losses inflicted by submarines were devastating to the Japanese merchant fleet, which could not replace its losses in men and material nearly quick enough. The statistics for the submarine force are even more remarkable when one considers the size of the US submarine fleet in relation to the rest of the Navy. The entire branch was staffed with 50,000 officers and men, representing only 1.6% of all naval personnel.[5] In return for their achievements, the American submarine force lost fifty-two submarines to all causes over the course of the war, resulting in the loss of 3500 officers and men. This gave the submarine force the highest casualty rate in the entire U.S. military, with 22% of men serving on war patrols being killed in action.[6] These figures are indicative of the remarkable performance given by the US submarine force during the Pacific War.

IJN submarines were substantially less successful during the war. This is in large part due to the Combined Fleet’s doctrine of using submarines as scouting units rather than merchant raiders. Over the course of the war, IJN submarines sank 184 merchant vessels for 907,000 tons.[7] They were also able to sink a number of warships, including two fleet carriers, a cruiser, and several destroyers in 1942 alone. However, Japanese successes decreased as the war went on and they were increasingly relegated to supply missions and other roles which took them away from Allied shipping lanes. They were also seriously hindered by catastrophic losses. The IJN began the war with 63 submarines and completed another 111 before the surrender. Of these 174 submarines, 128 were sunk during wartime. Many of those which did survive the war were training ships or had only just finished construction, meaning that very few of Japan’s fleet submarines were operational at the end of the war.[8]

Considering how deadly that the U.S. submarines proved to be to the IJN surface fleet and the Japanese merchant fleet in particular, it is surprising that this aspect of the Pacific War has received such little attention over the years. Despite encountering problems with its submarines, captains, and especially its torpedoes, the US Navy’s submarines were extremely effective in limiting the number of supplies which made it Japanese garrisons across the Pacific. Conversely, the IJN, despite having a very capable submarine fleet at the start of the war, had relatively little to show for its efforts at the time of the surrender. The most crucial element of the US success and IJN disappointment was the US Navy’s willingness to change its strategy with regard to its submarines, turning them loose on Japanese shipping lanes to make them as effective as possible. This, coupled with the US’ ability to quickly produce fleet submarines and well-trained crews to man them made the US submarine force large and effective force which wreaked havoc on Japanese supply lines and hindered their ability to fight.

[1] 153, Joel Ira Holwitt, Execute against Japan: Freedom-of-the-seas, the U.S Navy, fleet submarines, and the U.S. decision to conduct unrestricted warfare, 1919-1941, 2005.

[2] 191-193, Carl Boyd and Akihiko Yoshida. The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995)

[3] 851-852, Clay Blair Jr. Silent Victory (Philadelphia & New York, PA & NY: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975)

[4] “Japanese Naval and Merchant Shipping Losses During World War II by All Causes”http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Japan/IJN/JANAC-Losses/JANAC-Losses-1.html 10/3/13

[5] 853, Clay Blair Jr. Silent Victory (Philadelphia & New York, PA & NY: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975)

[6] 851, Clay Blair Jr. Silent Victory (Philadelphia & New York, PA & NY: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975)

[7] “Submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy” http://www.combinedfleet.com/ss.htm 10/3/2013

[8] “Submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy” http://www.combinedfleet.com/ss.htm 10/3/2013