Submarines in the Pacific War Part I

/World War II saw the widest use of submarines in combat in any conflict since the vessel was first invented. While the campaign against the German U-boats in the Atlantic is a familiar subject, much less well known is the topic of submarine warfare in the Pacific. This is surprising, given the impact which the US Navy’s submarines had upon the supply of Japanese island bases on Pacific islands, as well as the ineffectiveness of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) submarine force. As the war progressed, US submarines greatly increased in numbers and effectiveness, going out on six-week long war patrols to stalk Japanese shipping lanes. By contrast, the IJN’s submarine force was whittled down due to accidents and sinkings, with the survivors being squandered on resupply missions and pointless special operations. The results of this campaign are even more surprising when one considers that the IJN perhaps one of the best submarine forces in the world prior to the start of the war.

By the time that the Second World War began, submarines had already seen combat in the American Civil War and First World War. The use of U-boats during the First World War had a particularly heavy impact on navies around the world who sought to wield a submarine force of their own as successfully as the Germans had. The period between the wars became a period of growth for the US Navy and the IJN, both of whom set about designing types of submarines specifically suited for their own battle doctrine.

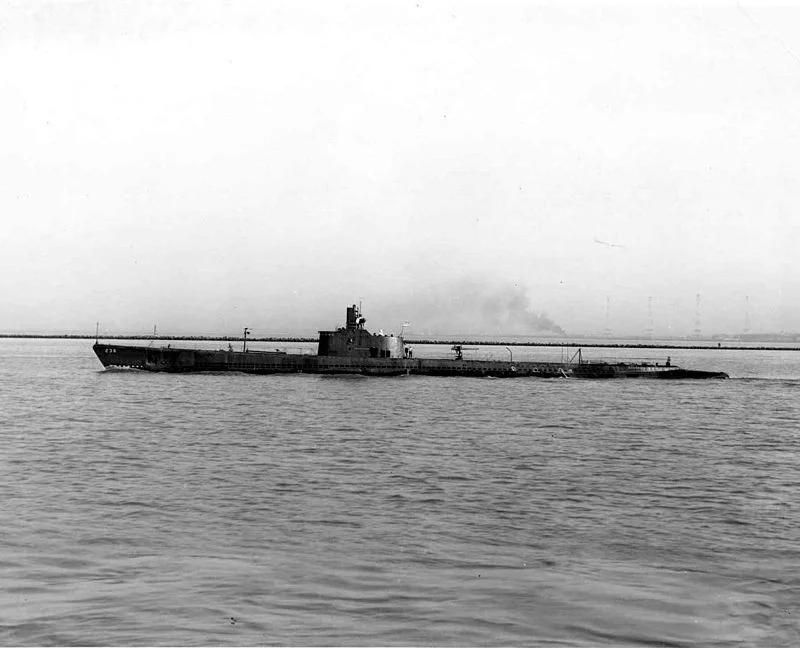

The eminent submarine design of the US Navy during the interwar period was the fleet boat, a type of submarine which was created a few years prior to the US entry into World War II. Fleet boat submarines were designed to be the scouts of the US Navy, ranging ahead of the surface fleet to report on enemy ship movements and attack targets to cause as much damage to fleets as possible. To fulfill their scouting mission, fleet boats were designed to travel quickly while on the surface, be able to stay at sea for long periods of time, dive deeper, and carry more weaponry. The Gato-class submarine design would make up the backbone of the US Navy’s submarine force during the Pacific War and shared the traits which characterized the typical fleet boat. Gato submarines were 312 feet long and displaced 1,800 tons when surfaced. They had a range of 20,000 miles and an endurance of about 75 days. Each Gato, crewed by 80+ officers and men, was armed with a medium-caliber deck gun for use against unarmed merchant vessels, 3-4 anti-aircraft guns, and ten torpedo tubes (with 24 torpedoes on board).[1] The Gato-class and the subsequent Balao-class submarines were the two most numerous types of US submarine used in the Pacific War and would be responsible for inflicting huge losses on Japanese merchant fleets.

The USS Silversides (SS-236), a Balao-lass fleet submarine, during the fall of 1944.

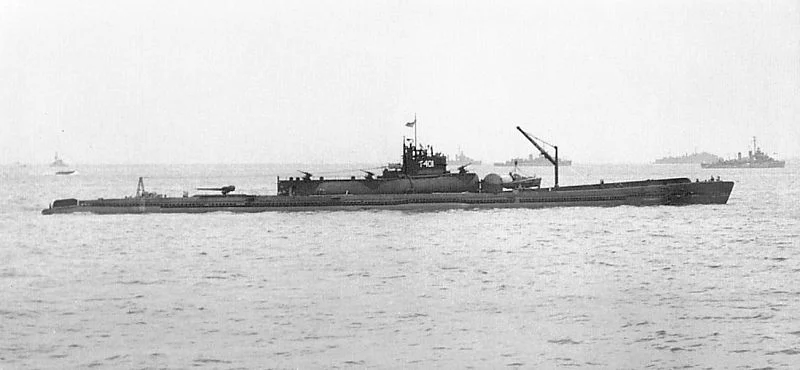

Unlike the US Navy, the IJN designed numerous types of submarines varying in size and in purpose. The IJN built submarines including: midget submarines, manned torpedoes, medium-range submarines, supply submarines (purpose-built), fleet submarines (many of which were built to carry aircraft in water-tight hangars), and submarines designed for high-speed underwater. The IJN built these many types of submarines to fit with their battle doctrine, which was structured around the concept of the decisive battle. In this scenario, IJN submarines were to be the scouts of the Navy, reporting on enemy warships and attacking when they could. To fulfill this role as well as other mission requirements, Japan constructed the most diverse submarine fleet of any navy. The IJN possessed the largest submarines built prior to the nuclear-powered submarines that became a staple of the Cold War. This was the I-400- class, three of which were in service at the end of the war. These submarines were 400 feet long, displaced over 5,000 tons while surfaced, and could carry three aircraft in their hangars.[2] However, the I-400-class was exceptional- a more typical class of Japanese submarine was the Type B1. The Type B1 was the most numerous IJN submarine, with twenty constructed during the Second World War. These submarines were 356 feet long, displaced 2,854 tons, had a range of 14,000 miles, were crewed by 94 officers and men, and held one seaplane in a forward hangar.[3]

The I-401, one of the four I-400-class submarines built by the IJN near the end of the war, flying the US flag after being captured by the US Navy.

In addition to submarine design, both the US Navy and the IJN made certain that the crews who manned their submarines were extremely capable. The US Navy subjected both officer and enlisted candidates to rigorous physical, mental, and aptitude tests. After going through a sixteen-week long trade school, candidates were subjected to further physical tests for admittance into submarine school. If a recruit made it into submarine school, he was required to learn every aspect of submarine life and duties. After several weeks of class-work, recruits were sent to sea aboard practice submarines to experience their first dives as well as operate the sub. Following graduation, newly-minted submariners were assigned to their first submarine and frequently required to become certified, a process which generally occurred during their first war patrol.[4] While US submariners were put through a strenuous training process and often experienced difficult conditions while at sea, the US Navy compensated them for their duties by supplementing their base pay with wartime bonuses, providing them with fresh food at the start of war patrols, shore leave during periods between war patrols, and rotation stateside to be reassigned to new submarines.

The IJN, similarly to the US Navy, was highly selective of the men who crewed its submarines. Cadet officers were sent to the Etajima Naval Academy, where they had to endure 17-hour work days, six and half days a week with only two relatively short seasonal breaks during the year. Officer recruits were also expected to maintain strict discipline at all times as well as go through intensive physical training.[5] Unlike US submariners, IJN recruits were required to reach the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade before applying to submarine school. Officers would then go through six months of submarine school and four months of additional training before being assigned to a training submarine. If the officer survived this grueling process, then he was assigned to an active boat. Enlisted men went through a similar rigorous routine of drill and classwork before being assigned to a vessel, passing through service schools and submarine school. After six months at submarine school, enlisted men were sent to the first vessel.[6] Once a Japanese sailor was a qualified submariner, he received surprisingly good treatment during his service at sea. IJN submariners received additional pay, though not as much as their American counterparts. Japanese submarines were well-stocked with provisions for good meals and snacks, just as US submarines. Japanese submariners even had access to some recreational facilities when off the submarine, though they were not nearly as extravagant as what was available to the Americans, as one I-boat captain related after the war: “I learned after the war that the American Navy leased the plush Royal Hawaiian Hotel at Wakiki Beach for its submariners, allowing them to have a full and relaxed rest between war patrols. Japanese submariners enjoyed nothing like that kind of comfort.”[7]

Given the intensive training and the relatively good treatment of crews and the amount of effort dedicated to submarine design and construction by both navies, it might strike some as odd that the US Navy’s submarines met with such huge successes, while the Japanese experienced few victories. There are a number of reasons for the US Navy’s success, one of the largest of which is the simple fact that the US Navy quickly changed its policy regarding how submarines would function during the war. These changes will be discussed in Part 2.

[1] Gato-class specifications (www.fleetsubmarine.com, 2002, 8/28/2013)

[2] http://www.combinedfleet.com/ships/i-400 8/29/2013

[3] http://www.combinedfleet.com/type_b1.htm 8/29/2013

[4] 11-14, Robert Hargis. US Submarine Crewman: 1941-1945. Oxford (u.a.: Osprey, 2003)

[5] 105-106, Zenji Orita and Joseph Daniel Harrington. I-boat Captain (Canoga Park, CA: Major, 1976)

[6] 198, Zenji Orita and Joseph Daniel Harrington. I-boat Captain (Canoga Park, CA: Major, 1976)

[7] 165, Zenji Orita and Joseph Daniel Harrington. I-boat Captain (Canoga Park, CA: Major, 1976)