Battlefield Visit: Stones River

/In an attempt to retake the important city of Nashville, a Confederate army commanded by General Braxton Bragg was engaged by the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, lead by Major General William Rosecrans, near the town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee at the close of 1862. The battle was to be one of the bloodiest of the Civil War.

By Seth Marshall

As the year of 1862 drew to a close, the situation for the Union was rather bleak. General George McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign had been turned back in Virginia, fought to a costly draw at Antietam, and had met a disastrous defeat at Fredericksburg. And while the Western Theater had not seen similar setbacks, neither had it seen significant progress towards pushing the Confederacy back. Commanders on both sides were under pressure from their governments to change the situation.

The Union’s Army of the Cumberland was commanded by Major General William Rosecrans. An 1842 graduate of the Military Academy at West Point, Rosecrans replaced Major General Don Carlos Buell, who had been heavily criticized for his failure to pursue Confederate General Braxton Bragg after his defeat at Perryville in October. Rosecrans was concerned about the ability to keep his army supplied during a campaign against the South. His hesitation caused much angst with his superior, Major General Henry Halleck, as well as with President Abraham Lincoln. Halleck wrote Rosecrans:

“The President is very impatient at your long stay in Nashville. The favorable season for your campaign will soon be over. You give Bragg time to supply himself by plundering the very country your army should have occupied. From all information received here, it is believed that he is carrying large quantities of stores into Alabama, and preparing to fall back partly on Chattanooga and partly on Columbus, Miss. Twice I have been asked to designate some one else to command, the Government demands action, and if you cannot respond to that demand some one else will be tried.”[1]

The Union commander was therefore under substantial pressure to counter the Confederate forces in middle Tennessee.

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM ROSECRANS. AN 1842 GRADUATE OF WEST POINT, ROSECRANS HAD TAKEN COMMAND OF THE ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND FROM MAJOR GENERAL DON CARLOS BUELL, WHO HAD BEEN CRITICIZED FOR HIS LACK OF ACTION.

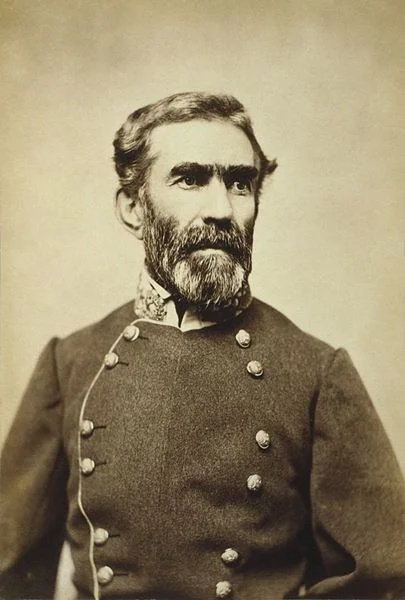

Rosecrans opposite number commanding the Confederate forces was General Braxton Bragg. Like Rosecrans, Bragg was a graduate of West Point, a member of the class of 1837. A veteran of the Mexican American War. Known for his highly abrasive personality and tendency to argue with other argues, Bragg was highly disliked by his subordinates. Described by southern diarist Mary Chestnut as having a “winning way of earning everyone’s detestation”[2], Bragg was so disliked by his officers and men that a number of them attempted to have him ousted from his command. However, Bragg was liked by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and remained in place.

GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG WAS THE COMMANDER OF THE CONFEDERACY'S ARMY OF THE TENNESSEE. A WEST POINT GRADUATE FROM THE CLASS OF 1837, BRAGG WAS HIGHLY SUSPICIOUS OF THE MEMBERS OF HIS STAFF AND EXTREMELY DISLIKED. DESPITE ATTEMPTS BY HIS STAFF TO REMOVE HIM, HE REMAINED IN COMMAND OF THE ARMY OF THE TENNESSEE.

Bragg made his move before Rosecrans in late 1862. He moved his army to Murphreesboro, 30 miles southeast of Nashville, Rosecrans’ base of operations. He intended to retake Nashville, thus depriving the North of a vital supply hub. However, his attack was delayed by supply shortages as well as reductions in the number of his troops. His delay allowed Rosecrans the time to get his army in order. The day after Christmas, Rosecrans began moving south towards Murphreesboro and arrived in the vicinity of Bragg on December 29th. The following day, both armies prepared to battle one another while the commanders laid their plans. Curiously, both generals planned to assault their opponents rights and roll up the other’s flank. As it transpired, Bragg would be the first to strike.

The tactical situation on December 30, 1862.

Early on the morning of December 31st, the 43,000 men of Rosecran’s army were either just waking or still sleeping.[3] Despite indications that the Confederate forces were preparing to attack, most Union commanders had not chosen to put their men on alert. Among these commanders was Major General Alexander McCook. He ignored the reports of increased activity and slept on. As a result, two of his divisions were unprepared for the Confederate assault, which began at 6 AM when Major General John McCown’s division led the attack into the Union lines. Most Union soldiers were just waking up and cooking breakfast and were caught by surprise; they did not present serious resistance before falling back. One of the brigades, 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Division, commanded by Brigadier General Edward Kirk, suffered 826 casualties of its 1,933 men, included Kirk himself, who was seriously wounded.[4]

The Confederate attack on the morning of the 31st.

The sole brigade who was prepared for battle was commanded by then-Brigadier General Phillip Sheridan. Sheridan had woken his men at 4 AM and ensured that they were manning their posts and guns when the Southerners attacked. Sheridan’s division came under attack at around 7 AM and would fight an effective withdrawal under fire fore the next four hours, claiming to having inflicted some 2,000-3,000 casualties while suffering 990 casualties out of its 5,000 men strength.[5] Sheridan’s performance bought the rest of Rosecran’s army time to establish a more defensible position. After he realized the seriousness of the situation, Rosecrans himself led from the front. “He rode all about the battlefield, asking for reports, giving succinct orders, and providing encouragement where needed, and it was much needed on that morning.”[6]

MAJOR GENERAL ALEXANDER MCCOOK, COMMANDER OF THE UNION'S RIGHT WING, DISREGARDED REPORTS OF CONFEDERATE ACTIVITY ALONG HIS FRONT AND DID NOT ORDER HIS MEN TO STAND TO AT DAWN. AS A RESULT, TWO OF HIS DIVISIONS WERE QUICKLY OVERRUN BY THE CONFEDERATE ATTACK.

Confederate forces pressed the attack through the morning. Union forces fell back on an area known as Round Forest. Artillery had been brought up to the Nashville turnpike, and on the approach of Confederate units began to fire as quickly as they could reload, inflicting heavy casualties. The Union continued to absorb heavy losses as well, among them was Rosecrans’ chief of staff, Colonel Julius Garesche, who was decapitated by a cannonball that just missed Rosecrans himself. Rosecrans, splattered with gore from his friend and West Point classmate, continued to lead the Union forces though shaken by Garesche’s violent death. The Union line held, having inflicted serious damage on numerous Confederate units, and the day finally came to an end.[7]

Confederate infantry, taking fire from the Union defensive line along the turnpike, struggle to advance across the cotton fields.

The tactical situation at the end of December 31st, following the Union withdrawal to the turnpike.

Both sides spent the first day of 1863 licking their wounds. Bragg was surprised that morning to find Rosecrans still in front of his position- the previous night, he had sent a telegram to Jefferson Davis proclaiming: “The enemy has yielded his strong position and is falling back. God has granted us a happy New Year.” On January 2nd, Bragg discovered that the Union had occupied a hilltop on his right. Desiring the terrain for his own artillery, Bragg ordered division commander Major General John Breckenridge to take the position. Breckenridge, aware of how difficult it would be to take such a strong position, protested the order, but Bragg overruled him. At 3PM, Breckenridge began massing his men in preparation for his attack. [8] Across the river, Breckenridge’s preparations had not gone unnoticed, and Rosecrans set about placing 58 guns in two positions to provide defensive fire. [9]

Confederate Major General John Breckenridge was very reluctant to mount the charge proposed by Bragg. Despite his protests, Bragg ordered him to carry out the attack.

Breckenridge's division attacks the Union positions atop a hill near the river.

One hour later, Breckenridge began his attack. Though the Union infantry put up a fierce fight, Breckenridge successfully overwhelmed their position an survivors began falling back across the river, taking refuge behind the line of artillery. Breckenridge’s initial attack had taken 400 prisoners and several flags. Across the river, Colonel John F. Miller, commanding a brigade from Negley’s Division, ordered his men to hold their fire until the retreating Union infantry passed through their lines. At this point, Breckenridge ordered his men to continue their attack, and they charged across the river- straight into the line of artillery and infantry. The Union guns poured fire into the charging Confederates and inflicted terrible casualties. One Confederate soldier later wrote:

“The nearest the Yankees came to getting me was shooting a hole in my pants and cutting my hair off my right temple. I know a peck of balls pass in less than a yard of me… The man in front of me got slightly wounded… the one on my right mortally and the one on my left killed.”

Union forces counterattack following the destruction of Breckenridge's Division.

The Confederate charge, which had been a success just minutes earlier, became a disaster. In less than an hour, Breckenridge’s division suffered 1800 killed or wounded.[10] As their attack fell apart, Miller ordered his men forward and swept the remaining Southerners back across the river and fields which they had just taken, capturing several Confederate guns and prisoners in the process. Eventually, Miller ordered his men back to their original position, where they remained until relieved.[11] As the survivors of Breckenridge’s attack made their way back to Southern positions, Breckenridge was reduced to tears, crying “My poor Orphans! My poor Orphans! My poor Orphan Brigade! They have cut it to pieces.”[12]

Breckenridge's Division, having sustained 1800 killed or wounded in less than an hour at the hands of 58 Union guns, retreat back across the river.

The annihilation of Breckenridge’s assault effectively ended the battle. Skirmishing would continue through the remainder of the 2nd and into the 3rd, but Bragg’s forces had taken serious losses, and with Union forces certain to receive reinforcements from Nashville, their position was untenable. On the night of the 2nd, Bragg met with his subordinates and agreed to retreat 36 miles south to Tullahoma, where the Army of Tennessee would go into winter quarters. Bragg suffered 10, 266 casualties, including over 1300 killed and 7900 wounded- these losses represented 27 percent of his army. The Army of the Cumberland suffered 13,200 casualties, including 1700 killed, 7800 wounded, and 3700 wounded- a 31 percent casualty rate. These casualty figures made the Battle of Stones River one of the bloodiest of the war.[13] Though a costly win, Rosecrans’ victory at Stones River secured Middle Tennessee for the Union for the remainder of the war. President Lincoln would later write to Rosecrans, remarking of the battle, “I can never forget, if I remember anything, that at the end of the last year and the beginning of this, you gave us a hard-earned victory, which had there been a defeat instead, the country instead, the country scarcely could have lived over.”[14] On January 4th, Rosecrans entered Murphreesboro and began constructing what eventually became known as Fortress Rosecrans, an enormous supply base with a large garrison and protected by numerous artillery batteries, to provide a forward staging base for continued operations in Tennessee.

Today, the area where the battle was fought has been preserved by the National Park Service. Established as a National Battlefield in 1927, the park incorporates much of the area over which the events of December 31, 1862- March 2, 1963 occurred. While the town of Murphreesboro has grown substantially in the intervening 150 years and portions of the former battlefield have been commercialized, the park includes a substantial portion of the ground over which the initial Confederate attack took place on December 31st. At the center of the park is a visitor center, which includes a small museum dedicated to explaining the events of the battle and sharing personal stories from the individuals who fought there. Numerous artifacts including a cannon, small arms, clothing, and personal artifacts are included in the exhibits. Across the street, a cemetery serves as the final resting place for many of the soldiers who fell during the battle, and a large memorial stands at its center. Visitors can follow miles of paths and retrace tactical movements of units during the battle, which are enumerated on by several placards placed around the battlefield. Also part of the park is the oldest Civil War monument in existence, the Hazen Brigade Monument, which was built in 1863. Not far outside of the park is the remains of Fortress Rosecrans, of which several earthen bastions remain standing- one of the large portions of the former defensive position has been incorporated into a separate park- many of the earthworks where Union guns once occupied remain and are accessible to visitors by wooden boardwalks. With these preservation efforts in place, Stones River National Battlefield is one the best preserved battlefields in the former Western Theater.

The entrance to Stones River National Battlefield.

Cannons mark the edge of one of the fields through which Confederate troops advanced.

An area known as the Slaughter Pen- Union troops held out here among the limestone outcroppings as long as they could, until Sheridan's troops ran out of ammunition and forced the troops here to retreat along with them.

Trenches remain from the positions that were occupied by the Pioneer Brigade.

A road and pedestrian path wind through the cotton field - the scene of the last Confederate assaults on December 31st- the Union had dug in along the turnpike, the position of which would be along the ride side of this picture.

It was at this position that 58 Union guns were assembled and inflicted terrible losses against Breckenridge's division during its attack on January 2nd.

A monument marks the spot where Union artillery halted Breckenridge's attack.

A monument to the Union dead who are buried in this cemetery stands at its center.

The oldest remaining Civil War monument stands at the former site of a battery of Union artillery, which was in part responsible for repelling the final Confederate attacks on the 31st.

Inside the remains of Fortress Rosecrans, one of the largest fortifications constructed during the war. The rises on the left are what remains of the earthen walls.

Sources

1. "The Battle of Stones River Summary & Facts." Civil War Trust. Civil War Trust. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

2. Cist, Henry. "The Battle of Stone's River (Union View)." The Battle of Stone's River (Union View). Civilwarhome.com, 1997. Web. 11 Apr. 2017

3. Cheeks, Robert. "Battle Of Stones River." HistoryNet. Wieder History Group, 29 Aug. 2006. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

4. Cheeks, Robert. "Battle of Stones River: Philip Sheridan's Rise to Millitary Fame." HistoryNet. Wieder History Group, 12 June 2006. Web. 11 Apr. 2017

5. Thompson, Robert. "New Year's Hell." Civil War Trust. Civil War Trust, 2014. Web. 11 Apr. 2017

6. "The Soldiers and the Battle of Stones River." Www.nps.gov. National Park Service, 02 June 2008. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

7. "A Hard-Earned Victory." National Park Service. National Park Service, n.d. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

[1] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/stones-river.html?tab=facts

[2] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/stones-river.html?tab=facts

[3] http://www.civilwarhome.com/stonesriverunion.html

[4] http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-stones-river.htm

[5] http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-stones-river-philip-sheridans-rise-to-millitary-fame.htm

[6] http://www.civilwarhome.com/stonesriverunion.html

[7] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/stonesriver/stones-river-history/new-years-hell-1.html

[8] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/stonesriver/stones-river-history/new-years-hell-1.html

[9] http://www.civilwarhome.com/stonesriverunion.html

[10]https://web.archive.org/web/20080602203526/http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/40stones/40facts1.htm

[11] http://www.civilwarhome.com/stonesriverunion.html

[12] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/stonesriver/stones-river-history/new-years-hell-1.html

[13]https://web.archive.org/web/20080602203526/http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/40stones/40facts1.htm

[14] https://www.nps.gov/stri/learn/historyculture/aftermath.htm