Film Review: Hacksaw Ridge

/By Seth Marshall

In his first film since Apocalypto (2006), director Mel Gibson has made a biopic about the first consciencious objector to win the Medal of Honor, Desmond Doss.

Before going into the review of the film, some context is required. Doss won the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Okinawa. The last major campaign of World War II, Okinawa became the bloodiest battle of the war for American forces. Okinawa is situated some 350 miles south of the Japanese mainland. Okinawa was viewed as a necessary stepping stone to an invasion of Japan itself. The island had several airfields that would place allied aircraft much closer to Japan than bases in the Mariana islands and China- it could also be used as a staging location for ground and naval forces prior to an invasion.[1] Okinawa would also be the first island with a large Japanese civilian population- before the war, some 500,000 civilians were living on Okinawa.[2] However, the island was heavily defended by some 150,000 Japanese forces, including 77,000 soldiers with the 32nd Army under the command of General Mitsuru Ushijima were reinforced with 20,000 “Boeitai”- Okinawa Home Guard conscriptees who were to be used for labor and support tasks. Additionally, 750 school boys were formed into a group called the “Tekketsu Kinnotai” –the “Blood and Iron Corps.”[3][4] The bulk of these forces were concentrated on the southern portion of the island, where a combination of rugged mountainous terrain and dense dug-in defensive preparations would make the area extremely difficult for American forces to take.

The landing zones for the Tenth Army and marine forces during the invasion of Okinawa.

The American movement during the Battle of Okinawa April 1-June 23.

Against the Japanese defenders, the Americans assembled a combine Army and Marine force of 183,000 men, supported by numerous warships and aircraft from the Navy’s Task Force 58. The invasion, which began on April 1, 1945, was preceeded by a seven-day bombardment by both naval guns and aircraft.[5] The initial landings encountered only light resistance, and by the end of the first day, several airfields had been taken further inland. It wasn’t until April 4th that the Army’s XXIV Corps began encountered the well-prepared Japanese defenses further south. The Marines continued to push north, advancing relatively quickly until April 13th until they reached Mt Yae Take. After four days of fighting, the Marines had secured the northern end of Okinawa. In the south, fierce fighting continued to slow the American advance. Despite the Americans’ overwhelming superiority in firepower, the Japanese were able to maintain their line by retreating to underground bunker before reoccupying their previous positions. It was not until the night of April 23-24 that the Japanese withdrew from the first defensive line to their second. The high casualties being inflicted on the American forces prompted the movement of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions into the front line, while the Army pulled its 27th Infantry Division off the line to make room for the reinforcements. That same day, the Japanese mounted an ill-advised counterattack. The Japanese 24th Infantry Division attacked the American lines in front of the 7th and 77th Infantry Divisions, and were met with intense fire. The counter-attack failed; some 7,000 Japanese soldiers were killed in the failed counterattack. It was in the weeks following this counterattack that Desmond Doss performed the actions which would earn him the Medal of Honor.

Two Marines carefully watch an Okinawan civilian surrendering.

An F4U Corsair drops napalm on a Japanese position while operating in close air support of Marine forces on the ground

A Stinson L-5 light observation plane flies over the ruins Naha, the largest city on Okinawa. Aircraft such as these operated as airborne artillery spotters.

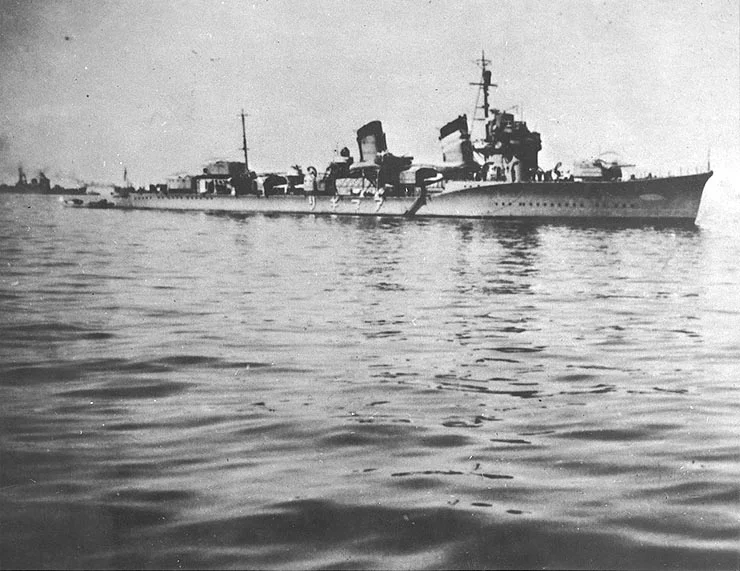

In addition to the intense action on land, the Japanese launched both aircraft and ships against the American fleet. During the battle, hundreds of kamikaze planes were sent towards US ships, each driven by the desire to crash into an American warship. On April 6th, 400 Japanese planes took off from Kyushu in the Japanese home islands- some 300 were shot down by American planes and anti-aircraft fire.[6] The following day, the last sortie by the Imperial Japanese Navy was undertaken. In an effort to provide relieve to their forces on Okinawa, the IJN sent the super battleship Yamato, the heavy cruiser Yahagi, and eight destroyers on what amounted to a one-way mission known as Operation Ten-Go. With not enough fuel for a return trip, it was decided that Yamato would expend its main gun ammunition on the invasion forces before beaching itself, after which its crew would fight on foot. En route, the task force was attacked by waves of aircraft from the US fleet. Hit by numerous 1,000lbs bombs and deadly torpedoes, the Yamato finally capsized at 2:23PM after a massive internal magazine explosion. 2,500 of her crew went down with the ship, with only 269 survivors being saved. The remainder of the force suffered no better- Yahagi was hit by seven torpedoes and twelve bombs and sunk with heavy loss of life, and four of the eight destroyers were also sunk. For this success, the Americans lost 10 aircraft with 12 aircrew killed.[7] Kamikaze attacks continued through April, resulting in the loss of 1,100 aircraft. Towards the end of May, 896 kamikaze raids were launched at the American fleet and at captured airfields. In the end, nearly 4,000 planes were shot down by either anti-aircraft fire or fighter patrols. [8]

The Yamato's magazines explode due to internal fires- she sank with the majority of her crew.

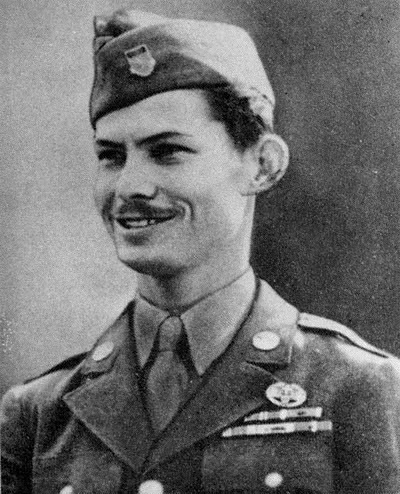

Doss was born in 1919 in Lynchburg, Virginia. Brought up as a Seventh-day Adventist, Doss’ religious beliefs in non-violence was cemented early in his life when he witnessed his father point a gun at his uncle. Doss’ mother put a stop to the confrontation by calling the police and telling Doss to hide the gun, but the event had a substantial impact on the young Doss, who thereafter vowed to never touch another gun.[9] In April 1942, he was drafted into the Army. Although he had worked in a shipyard and would have been eligible to stay there as a defense worker, he chose to go into the Army as a conscientious objector instead. Following a contentious period of training, Doss was assigned to the 307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division and sent to the Pacific. While the film only shows Doss’ actions on Okinawa, he also served on Guam and Leyte. During this time, he earned a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart for his actions and for wounds sustained.[10]

Desmond Doss following the end of the war.

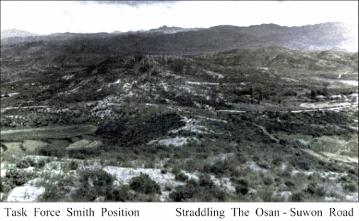

On April 28th, 1945, after securing Ie Shima Island, the 77th Division replaced the 96th Division in the line on Okinawa.[11] On May 1, Doss’ company scaled a 400 foot-high ridge known as Maeda Escarpment. His unit took heavy casualties from artillery, mortar and machinegun fire and withdrew. Doss, however, stayed behind. He later recalled, “I had these men up there and I shouldn’t leave ‘em… They were my buddies, some of the men had families, and trust me. I didn’t feel like I should value my life above my buddy’s. So I decided to stay with them and take care of as many as I could. I didn’t know how I was gonna do it.” After fashioning a sling with what rope he could find, Doss spent the next 12 hours saving as many men as a he could, lowering them one at a time to safety. By Doss’ own estimation, he eventually saved some 50 men. His commander wanted to credit him with saving 100, so the compromise figure of 75 was reached for his Medal of Honor citation. After returning from the ridge, Doss participated in the final attack on the Maeda Escarpment on May 5th. Though the day was a Saturday and therefore the Sabbath, Doss agreed to forgo his normal practice of no work to take part in the attack, as he was the sole remaining medic in his company. However, he successfully requested that the assault be delayed in order for him to read his Bible and pray. [12]

Doss stands at the top of Maeda Escarpment after placing cargo nets on the side of the cliff- Doss was one of the volunteers who carried the net to the top.

Members of the 77th Infantry Division during a rainstorm on Okinawa.

Several weeks later, on May 21, Doss was treating wounded soldiers when a hand grenade landed in the foxhole he was in. “They begin to throw these hand grenades… I saw it comin’. There was three other men in the hole with me. They were on the lower side, but I was on the other side lookin’ when they threw the thing. I knew there was no way I could get at it. So I just quickly took my left foot and threw it back to where I though the grenade might be, and throw my head and helmet to the ground. And not more than half a second later, I felt like I was sailin’ through the air. I was seein’ stars I wasn’t supposed to be seein’, and I knew my legs and body were blown up.”[13] Riddled with shrapnel, Doss was evacuated from the battlefield.

The Battle of Okinawa would finally come to an end nearly a month after Doss was wounded. On the morning of June 22, General Ushijima committed seppuku along with his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Isamu Cho. After 82 days, the battle was over.[14] It was the costliest battle of the Pacific War for the United States- over 12,000 US servicemen were killed and nearly 37,000 wounded. The Navy sustained its heaviest casualties for a single battle during the war- 4,907 killed or missing, with 4600 wounded, along with 36 ships sunk and 368 damaged- a result of the intense kamikaze attacks.[15] Among the dead was General Simon Buckner, commander of the Tenth Army, killed on June 18th by an artillery shell.[16] However, Japanese losses were even more appalling- 107,000 killed, 7,400 taken prisoner, and 20,000 missing, possibly incinerated.[17] The worst losses were suffered by Okinawa civilians, of whom some 100,000 died during the battle.[18] The consideration of the battle’s ferocity ultimately played a factor in the US’ decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

After the war ended, Doss was sent back to the US. On October 12th, 1945, he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman. The war had taken a toll on Doss though. For five and a half years after the war he was in and out of hospitals attempting to recover from both his wounds and from tuberculosis which he had contracted on Leyte. Eventually, five of his ribs and one of his lungs were removed before he was finally released from the hospital in August 1951. He eventually became deaf, as a result he believed from the antibiotics that the military continued to prescribe to him. He received a disability pension from the military, but struggled to make ends meet. His wife took a full time job as a nurse, while worked a variety of odd-jobs including cabinet-making, fish farmer, salesman, and maintenance technician. In 1991,his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer. In November that year, Doss and his wife were involved in a car accident as he was driving her to a treatment session- his wife later passed away from injuries suffered in the crash. Doss remarried in 1993 to Francis Duman- they remained together until his death in 2006 at the age of 87.

President Harry Truman awards Doss the Medal of Honor on October 12, 1945.

The film Hacksaw Ridge, which released on November 4th, is Mel Gibson’s first directorial effort since his 2006 film Apocalypto. James Garfield, known best for his roles in the The Social Network and both of the Amazing Spiderman films, stars as Desmond Doss. Supporting cast includes Sam Worthington as Captain Glover, Vince Vaughn as Sergeant Howell, and Hugo Weaving as Doss’ father. For the most part, Gibson has faithfully recreated the actual events surrounding Doss’ life, though there has been artistic license taken, particularly with regard to Doss’ court martial. While it is true that his superiors, including his company commander, Captain Glover, attempted to have him thrown out of the Army, they did not court-martial him. His superiors tried to have him kicked from the Army for “mental instability”, also known as a Section 8. However, when Doss was called to the hearing, he said that he could not accept a Section 8 because of his religion. His superior officers relented. He was also heckled endlessly by other soldiers in his unit, who frequently referred to him as “Holy Jesus” and “Holy Joe”. [19]Other officers tormented him as well- a Captain Cunningham threatened Doss with a court-martial for not completing rifle training. He later would deny Doss passes to see his wife and family. [20]

James Garfield stars as Desmond Doss.

The other major departure from actuality was how it shows Doss is wounded. The film shows Doss as being wounded by a grenade during the final assault on Maeda Escarpment on May 5th, 1945. However, it was not until the night of May 21st that Doss was wounded, and under circumstances so extraordinary, that the actual events were apparently not included in the film because it was felt by Gibson that the audience would not believe them to be true after having watched him save so many soldiers by himself. After Doss attempted to kick a grenade away from his comrades and was wounded by shrapnel, he waited for five hours for fellow soldiers to reach him with a stretcher. As he was carried away, he saw another soldier more badly wounded than himself and gave up the stretcher for the other man. While waiting for another stretcher to arrive, Doss was wounded again when a sniper’s bullet that caused a compound fracture to his left arm. He used a fallen rifle as a split, then crawled for 300 yards to safety.[21]

Despite these errors, the film is overall a good production. The combat scenes are very intense and of good quality, surprising for a film that was made with only $40 million (for reference ,Saving Private Ryan, released in 1998, was made with $70 million).[22] This being said, it would be a stretch to call this film truly great. It is certainly better than previous movies focusing on the Pacific War, but it seems to have fallen somewhat into the trap which has snared other more recent war films, and that is to make by-the-numbers war film that doesn’t distinguish itself from the pack. Hacksaw Ridge is certainly a movie worth seeing, but not a dramatic trend breaker that differs much from contemporary war films.

Sources

1. Frame, Rudy R., Jr. "MCA&F." Okinawa: The Final Great Battle of World War II | Marine Corps Association. Marine Corps Gazette, Nov. 2012. Web. 23 Nov. 2016

2. Dong, Christopher. "Exploring Okinawa's World War II History." CNN. Cable News Network, 13 Mar. 2015. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

3. "Battle Of Okinawa: Summary, Fact, Pictures and Casualties." HistoryNet. N.p., 04 Aug. 2016. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

4. Tsukiyama, Ted. "THE HAWAI'I NISEI STORY Americans of Japanese Ancestry During WWII." Www.hawaii.edu. Hawaii Nisei Rights Movement, 2006. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

5. Hacksaw Ridge vs the True Story of Desmond Doss, Medal of Honor." HistoryvsHollywood.com. CTF Media, n.d. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

6. Goldstein, Richard. "Desmond T. Doss, Heroic War Objector, Dies." The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 25 Mar. 2006. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

7. US Naval Institute Staff. "Mel Gibson, Vince Vaughn Talk Battle of Okinawa Movie 'Hacksaw Ridge'" USNI News. Unleashed Technologies, 05 Nov. 2016. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

[1] https://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/2012/11/okinawa-final-great-battle-world-war-ii#

[2] http://www.cnn.com/2015/03/12/travel/okinawa-world-war-ii-travel/

[3] http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-okinawa-operation-iceberg.htm

[4] http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149316185200.html

[5] http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149316185200.html

[6] http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149316185200.html

[7] www.warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/japanese-battleship-yamato-make-its-final-stand/

[8] http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149316185200.html

[9] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[10] http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/25/us/desmond-t-doss-87-heroic-war-objector-dies.html

[11] www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/cc/077id.htm

[12] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[13] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[14] http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-okinawa-operation-iceberg.htm

[15] http://www.cnn.com/2015/03/12/travel/okinawa-world-war-ii-travel/

[16] http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-okinawa-operation-iceberg.htm

[17] www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-two/the-pacific-war-1941-to-1945/the-battle-of-okinawa/

[18] http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149316185200.html

[19] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[20] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[21] http://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hacksaw-ridge/

[22] https://news.usni.org/2016/11/03/mel-gibson-vince-vaughn-talk-movie-hacksaw-ridge